Most common indication for lung transplantation is emphysema.

Most common indication for lung transplantation is emphysema.

More than 2500 lung transplantations performed annually worldwide, and about 1500 are done in the US.

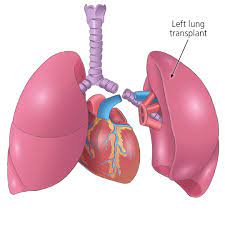

Lung transplantation, or pulmonary transplantation, is a surgical procedure in which one or both lungs are replaced by lungs from a donor.

Donor lungs can be from a living or deceased donor.

A living donor can only donate one lung lobe.

Some lung diseases may only need to receive a single lung, while other lung diseases such as cystic fibrosis need to receive two lungs.

Lung transplants can also extend life expectancy and enhance the quality of life for those with end stage pulmonary disease.

Lung transplantation is a measure of last resort for patients with end-stage lung disease who have exhausted all other available treatments without improvement.

Conditions that may make such surgery necessary:

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), including emphysema;

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

cystic fibrosis

idiopathic pulmonary hypertension

alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency

replacing previously transplanted lungs that have since failed

bronchiectasis and sarcoidosis

Contraindications:

Certain conditions may make a person a poor candidate for lung transplantation:

Concurrent chronic illness: congestive heart failure, kidney disease, liver disease

Current infections, including HIV and hepatitis

However, hepatitis C patients are both being transplanted and are also being used as donors if the recipient is hepatitis C positive.

Similarly, select HIV-infected individuals have received lung transplants after being evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Current or recent cancer

Current use of alcohol, tobacco or illegal drugs

Age

Psychiatric conditions

History of noncompliance with medical instructions

Requirements for potential donors:

Requirements for potential lung donors:

Size match: donated lung or lungs must be large enough to adequately oxygenate the patient, but small enough to fit within the recipient’s chest cavity

Blood type

Requirements for potential recipients:

End-stage lung disease

Has exhausted other available therapies without success

No other chronic medical conditions of heart, kidney, liver.

No current infections or recent cancer.

Some patients with lung cancer or other cancers, may be allowed.

In certain cases where pre-existing infection is unavoidable, as with many patients with cystic fibrosis.

No HIV or hepatitis, although some recipients with the same type of hepatitis as the donor can receive a lung, and individuals with HIV who can be stabilized and can have a low HIV viral load may be eligible.

No alcohol, smoking, or drug abuse

Marked undernourishment or obesity are both associated with increased mortality.

Acceptable psychological profile

Has a social support system

Able to comply with post-transplant regimen.

Blood typing; the recipient’s blood type must match the donor’s, due to antigens that are present on donated lungs.

A mismatch of blood type can lead to a strong response by the immune system and subsequent rejection of the transplanted organs.

Tissue typing; ideally should match as closely as possible between the donor and the recipient, but the desire to find a highly compatible donor organ must be balanced against the patient’s immediacy of need.

Chest X-ray – PA & LAT, to verify the size of the lungs and the chest cavity

Pulmonary function tests

CT Scan=Thoracic & Abdominal

Bone mineral density scan

MUGA scan

Cardiac stress test (Dobutamine/Thallium scan)

Ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scan

Electrocardiogram

Cardiac catheterization

Echocardiogram

Lung allocation score: prospective lung recipients of age of 12 and older are assigned a lung allocation score or LAS, which takes into account various measures of the patient’s health.

The new system allocates donated lungs according to the immediacy of need rather than how long a patient has been on the transplant list.

Patients who are under the age of 12 are given priority.

The length of time spent on the list is also the deciding factor when multiple patients have the same lung allocation score.

Types of lung transplant:

A lobe transplant is a surgery in which part of a living or deceased donor’s lung is removed and used to replace the recipient’s diseased lung.

Donors should be able to maintain a normal quality of life despite the reduction in lung volume.

Many patients can be helped by the transplantation of a single healthy lung,from a donor who has been pronounced brain-dead.

Patients may require both lungs to be replaced, especially for people with cystic fibrosis, due to the bacterial colonization commonly found within such patients’ lungs.

If only one lung were transplanted, bacteria in the native lung could potentially infect the newly transplanted organ.

Some respiratory patients may also have cardiac disease which would necessitate a heart transplant: a domino transplant.

A single lung transplant takes about four to eight hours, while a double lung transplant takes about six to twelve hours to complete.

A history of prior chest surgery may complicate the procedure and require additional time.

In single-lung transplants, the lung with the worse pulmonary function is chosen for replacement.

The right lung is usually favored for removal because it avoids having to maneuver around the heart, as would be required for excision of the left lung.

In a singular lung transplant the lung is collapsed, the blood vessels in the lung tied off, and the lung removed at the bronchial tube.

The donor lung is placed, the blood vessels and bronchial tube reattached, and the lung reinflated.

A double-lung transplant, also known as a bilateral transplant, can be done either sequentially, en bloc, or simultaneously.

Sequential is more common than en bloc: equivalent to having two separate single-lung transplants done.

The transplantation process starts after the donor lungs are inspected and the decision to transplant has been made.

In 10% to 20% of double-lung transplants the patient is hooked up to a heart-lung machine which pumps blood for the body and supplies fresh oxygen.

The average hospital stay following a lung transplant is generally one to three weeks.

Patients are typically required to attend a rehabilitation program for approximately 3 months to regain fitness.

Certain nerve connections to the lungs are cut during the procedure, so transplant recipients cannot feel the urge to cough or feel when their new lungs are becoming congested.

Lung transplantation patients must make conscious efforts to take deep breaths and cough in order to clear secretions from the lungs.

The heart rate response is less quick to exertion due to the cutting of the vagus nerve that would normally help regulate it.

Patient may notice a change in their voice due to potential damage to the nerves that coordinate the vocal cords.

Exercise enhances muscle strength, increase bone mineral density as well as improvements in 6 minute walking time.

Immunosuppressant drugs are required to prevent transplant rejection.

Which make recipients vulnerable to infections.

Complications of lung transplant: bleeding, infection, rejection, failure to properly heal and function, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder, gastrointestinal inflammation and ulceration of the stomach and esophagus.

Transplant rejection may occur both immediately after the surgery and continuing throughout the patient’s life.

Signs of rejection:

fever, flu-like symptoms, including chills, dizziness, nausea, general

feeling of illness, night sweats;

increased difficulty in breathing;

worsening pulmonary test results;

increased chest pain or tenderness;

increase or decrease in body weight of more than two kilograms in a 24-hour period.

The immunosuppressive regimen is begun just before or after surgery, and usually includes cyclosporine, azathioprine and corticosteroids.

Episodes of rejection may reoccur throughout a patient’s life, the exact choices and dosages of immunosuppressants may have to be modified over time.

Other agents include tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil.

Chronic rejection, meaning repeated bouts of rejection symptoms beyond the first year after the transplant surgery, occurs in approximately 50% of patients.

Such chronic rejection presents itself as bronchiolitis obliterans, or less frequently, atherosclerosis.

The lung transplant survival rate one year after transplant is as high as 88 percent.

After 3 years, the lung transplant survival rate is 73 percent.

The 5-year lung transplant survival rate is 60 percent.

The ten-team survival rate is about 28%.

Transplanted lungs typically last three to five years before showing signs of failure.

A study of nearly 10,000 lung transplant recipients demonstrated significantly improved long-term survival using sirolimus + tacrolimus (median survival 8.9 years) instead of mycophenolate mofetil + tacrolimus (median survival 7.1 years) for immunosuppressive therapy starting at one year after transplant.