One of the most critical interventions in emergency settings.

One of the most critical interventions in emergency settings.

It is a high risk procedure commonly performed in critically ill patients.

More than 1.5 million patients undergo tracheal intubation each year in the US.

Short term is associated with minimal complications but with mechanical ventilation longer than 1 week associated with adverse outcomes.

Studies indicate that sedation greatly improves the ease and safety of tracheal intubation.

As many as 40% of tracheal intubations in the ICU are complicated by hypoxemia, which may lead to cardiac arrest and death.

Hypoxemia occurs during 10 to 20% of tracheal intubations in the emergency department or ICU is associated with cardiac arrest and death.

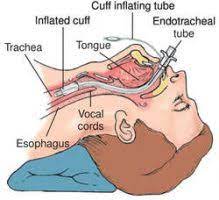

Appropriate position is >1cm above the carina.

In children the trachea is significantly shorter than in adults making it more difficult for proper placement.

The tube is easily displaced by rotation, flexion and head extension.

Right mainstem intubations common.

Confirmation of proper tube placement achieved by auscultation of bilateral lung sounds.

Auscultation in children not as reliable as in adults to confirm proper tube placement.

Appropriate insertion depth estimated to be 3 x endotracheal tube size.

Failure to intubate the trachea on the first attempt occurs in 20 to 30% of tracheal intubations performed in emergency settings and is associated with increased risk of life-threatening complications.

Chest x-ray best way to evaluate tube position.

Plays a central role in contemporary emergency medical care, but remains controversial.

Paramedic endotracheal tube insertion is associated with significant rates of unrecognized tube misplacement or dislodgement, need for multiple attempts, and insertion failure.

In a randomized clinical trial of 1102 critically ill patients undergoing tracheal intubation, use of a bougie did not significantly increase the incidence of successful intubation on the first attempt compared with the use of an endotracheal tube with stylet.

Hypotension occurs during 25 to 40% of tracheal intubations in the ICU and can lead to cardiac arrest and death.

Hypotension during tracheal intubation is the result partly from medication induced vasodilation and decreased return of venous blood to the heart due to increase intrathoracic pressure from positive pressure ventilation.

Current guidelines recommend that critically ill patients undergoing tracheal intubation receive a fluid bolus.

Fluid bolus is administered during approximately 40 to 50% of emergency tracheal intubations in current clinical practice: however, in a randomized clinical trial of 1065 critically ill adults the incidence of cardiovascular collapse was no difference with or without ministration of the fluid bolus(Russell DW).

Endotracheal tubal insertion is associated with iatrogenic hyperventilation and chest compression interruptions.

Failure to intubate occurs in fewer than 1/5000 elected general anesthesia procedures and requires surgical airway rescue in fewer than 1/50,000 cases.

Failure to intubate can result in major complications associated with long-term morbidity and account for 25% of an anesthesia related deaths.

Peri-intubation events associated with underlying shock, respiratory failure, metabolic acidosis and other pathophysiological changes increase the risk of adverse events in such critically ill patients compared with patients undergoing intubation in the operating room.

25% of tracheal tubes inserted by paramedics in prehosptial emergencies are misplaced, and approximately 50% of those patients with a misplaced tube die in the emergency room.

Up to 28% of critically ill patients undergoing tracheal intubation may experience a life-threatening complication such as severe hypoxemia or hemodynamic instability and 2.7% of such procedures are complicated by cardiac arrest.

Among critically ill patients undergoing to tracheal intubation worldwide at least one major clinical event occurred after intubation and 45.2% of patients, including cardiovascular instability in 42.6%, severe hypoxemia and 9.3%, and cardiac arrest in 3.1%. (IN-TUBE Study Investigators).

First pass success rate for emergency airway intubation is 84.1%.

The use of video intubation technology has improved the intubation technique.

Among neonates undergoing urgent endotracheal intubation, video laryngoscopy, resulted in the greater number of successful intubations on the first attempt than direct laryngoscopy.

The use of video laryngoscopy has increased the success rate of intubation.

Laryngeal mask airway uses a screen, camera, and light source and has a large opening through which an endotracheal tube can be passed.

Video laryngoscopy is associated with an increase in the success rates of first pass intubation from 87.8-95.2% and a decline in the success rate of direct delivery endoscopy from 90.8-75.5%.

Among critically, ill adults, undergoing tracheal intubation in an emergency setting, the use of video laryngoscope results in a higher incidence of successful intubation in the first attempt rgan the use of direct laryngoscope (Prekker, ME).

Hyperangulated video laryngoscopy decreased the number of attempts needed to achieve endotracheal intubation compared with direct laryngoscopy and is a preferable approach for intubating patients undergoing surgical procedures (Ruetzler K).

Most common cause of hoarseness postoperatively in patients undergoing procedures that do not involve the head and neck is swelling of the vocal cords.

For critically ill patients undergoing tracheal intubation, the nearly simultaneous administration of a sedative and a neuromuscular blocking agent facilitate intubation on the first laryngoscopy attempt.

In a randomized clinical trial of 1102 critically ill patients undergoing tracheal intubation, use of a bougie did not significantly increase the incidence of successful intubation on the first attempt compared with the use of an endotracheal tube with stylet.

Succinylcholine is traditionally the preferred neuromuscular blocking agent.

Rapid sequence intubation involves the administration of rapid onset drugs including a hypnotic and a paralytic agent: the use of a neuromuscular blocking agent improves the overall intubating conditions and first attempt intubation success rate, regardless of the choice of induction agent.

For critically ill patients rapid sequence induction involves a delay of 45-90 seconds between medication administration and initiation of laryngoscopy.

For critically ill patients providing positive pressure ventilation with a bag mask device during this interval prevents hypoxemia without increasing the risk of a gastric or oral pharyngeal aspiration. (Prevent trial).

Incubating conditions associated with coughing, resistance to laryngoscope blade insertion and limb movement are associated with a greater incidence of postoperative hoarseness and laryngeal injuries.

By adding neuromuscular blockers at induction of anesthesia, the incidence of postoperative hoarseness dramatically decreases.

Complications of prolonged treatment are ventilator associated pneumonia, persistent sedation and subglottic stenosis.

Postextubation laryngeal edema is one of the most common and severe complications.

Incidence of postextubation laryngeal edema can be as high as 22%.

Laryngeal edema typically occurs shortly after extubation and is more common in those who have more than 36 hours of intubation.

Postextubation laryngeal edema can cause prolonged mechanical ventilation.

12 hour pretreatment with methylprednisolone before a planned extubation in patients ventilated more than 36 hours is highly effective in reducing incidence of postextubation laryngeal edema and reintubation.

Prolonged intubation leads to edema, inflammation and ulceration of the laryngeal and tracheal mucosa, particularly at the vocal cords and the site of the cuff.

United kingdom study showed that one of 22,000 cases of tracheal intubation was associated with severe adverse airway management events in the operating room, such as death, brain damage, and need for an emergency surgical airway, or unplanned ICU admission.

Neonatal endotracheal intubation often involves multiple attempts, and oxygen desaturation is common: nasal high flow therapy during the procedure improves the likelihood of successful intubation on the first attempt without physiological instability in the children (Hodgson KA).

Pre-oxygen, the administration of supplemental oxygen before induction of anesthesia, increases the content of oxygen in the lung at induction and decreases the risk of hypoxemia during the tracheal intubation procedure.

Among critically ill adults undergoing tracheal intubation, pre-oxygenation with non-invasive ventilation results in a lower incidence of hypoxia during the intubation process, than pre-oxygenation with an oxygen mask (Gibbs, W).