Also known as the apical ballooning syndrome, broken heart syndrome and stress induced cardiomyopathy.

Also known as the apical ballooning syndrome, broken heart syndrome and stress induced cardiomyopathy.

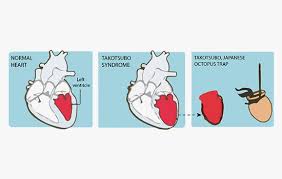

Abnormal left ventricle caused by prolonged stress.

A transient cardiomyopathy after a stressful event in the absence of a coronary artery disease.

The pathophysiology of stress cardiomyopathy is debated, and the leading hypothesis is that catecholamine access is the primary driving force, and beta blockers therapies frequently used to prevent recurrence.

Predominately apical left ventricular dysfunction.

One study found that 50% of patients with stress cardiomyopathy and obstructive coronary artery disease on angiography.

Regional wall motion abnormality can be detected by left ventricularography, in the catheterization laboratory, by transthoracic echocardiography, or magnetic resonance imaging.

Regional wall motion abnormalityies involves hypokinesis or akinesis of the mid and apical segments of the left ventricle that do not correspond with any single coronary artery distribution with sparing of the basal systolic function.

The right ventricle can be involved in exhibit similar regional wall motion abnormality‘s in a minority of patients.

The heart suddenly weakens and causes the left ventricle to balloon out into the shape of a Japanese octopus trap.

Approximately 2% of all patients suspected of having acute coronary syndrome end up with Tako-subo syndrome.

Approximately 50,000-100,000 cases per year in the US.

Estimated 7c-14,000 patients are diagnosed annually, and most are postmenopausal women.

A stress cardiomyopathy characterized by acute, profound but reversible left ventricular dysfunction in the absence of significant coronary artery disease, triggered by emotional and physical distress.

An acute and reversible process of left ventricular dysfunction associated with a Takotsubo pot (Octopus trap) shaped cardiomyopathy.

Involving a transient left ventriclular dysfunction and chest pain in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease.

Triggers include emotional stressors such as a death in the family, work problems, divorce or physical stress following a car crash, surgery, or fall.

Stresses that precipitate Takotsubo cardiomyopathy include physical stress, emotional stress, non-cardiac surgery procedures, and critical illness requiring ICU management.

In one third of patients no trigger is identified.

Syncope is a presenting symptom and 7.7% of patients.

Left ventricular apical thrombus formation is a known complication of this process and is reported in up to 8% of cases, with potential embolic complications (Haghi D et al).

Catecholamine access is believed to lead to sympathetic overstimulation and myocardial stunning.

Plasma catecholamine levels higher in patients with this disease process than in patients with ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction (Wittstein IS et al).

Possible mechanisms include epicardial coronary artery spasm induced by ischemia, right microvascular spasm, direct catecholamine mediated myocyte injury and changes in beta adrenergic receptor signals.

Catecholamines nor epinephrine and epinephrine induced platelet activation and can mediate endothelial and cardiomyocyte injury.

Catecholamine surges can induce myocyte injury via the cyclic adenosine monophosphate-mediated calcium overload.

Suggested that a surge in catecholamine concentration can lead to let ventricular dysfunction.

It is suggested at the syndrome begins with elevated levels of the vasoconstrictor endothelium – 1 and coronary microvascular vasoconstriction.

Associated with acute onset of akinesis of the apical and mid portions of the left ventricle, with apical ballooning

No significant coronary artery findings are present on angiogram.

Accompanied with chest pain, EKG changes and limited increase in cardiac enzymes.

Causes chest pain and dyspnea.

Clinical presentation of stress cardiomyopathy is typically indistinguishable from acute coronary syndrome.

Patients typically present with substernal chest pain, dyspnea, uncommonly with syncope or rarely with cardiac arrest.

Patients may have pulmonary edema, elevated cardiac biomarkers, or ischemic changes on ECG.

There is a disproportionate low level of cardiac enzyme elevation compared to the extent of cardiac akinesia.

Cardiac catheterization does not reveal substantial obstructive lesions in the coronary arteries.

Estimated 2% of patients presenting with suspected acute coronary syndromes actually have this process.

It is common to develop acute failure, however only 10% develop hemodynamic instability and cardiogenic shock.

Reference regular basal hyperkinesis can lead to less ventricular outflow tract obstruction.

Reported in all ethnic groups, but is uncommon in Hispanics and African-Americans.

In a large registry 27% of patients with stress cardiomyopathy had an acute, chronic or previous episode of neurologic disorder including, intracranial bleeding.

Most patients have no prior cardiac history.

Most frequent presentation is chest pain (66%) and 14% have dyspnea.

The left ventricular dysfunction is reversible in most cases.

Syndrome is frequently preceded by acute severe emotional or psychological distress.

Triggers initially were thought to be only emotionally sad events, but happy news may also be precipitants, a term known as happy heart syndrome.

The syndrome occurs almost exclusively in postmenopausal women in their 6-7,the decade of life in the setting of a strong emotional distress.

Women 50 years or older represent 90% of the cases, with emotional trigger being the most common.

Men represent 10% percent of cases and most likely to be affected by a physical trigger.

May occur following the administration of pharmacological agents such as dobutamine, vasoconstrictor agents that act as Alpha adrenergic receptor stimulants, serotonin specific reuptake inhibitors, adrenergic agents, anticholinergic or parasympathetic drugs, and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitorrs, or invasive medical procedures.

Cerebrovascular accidents produce left ventricular dysfunction because of excess catecholamine production and is associated with 10 fold higher odds of this syndrome.

Increased prevalence in women: female:make 9:1.

In Japan it is more common in men.

70% of cases are triggered by emotional or physical stress.

Suggested it is related to acute and excessive elevation of catecholamines, calcium overload with direct myocytes damage, estrogen depletion, multiple vessel epicardial coronary spasm or diffuse micro vascular spasms.

High incidence in postmenopausal women.

Prevalence of approximately 2% of patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome.

EKG may be normal but can have nonspecific ST and T wave changes.

70% of cases associated with ST-elevation in the anterior precordial leads.

Per ordinal T-wave inversions and ST-segment elevations are the most common ECG findings in stress cardiomyopathy.

There is less inferior reciprocal ST-depression than is typically seen with and anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Frequently diagnosed as having ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Majority of patients have the clinical presentation similar to that of acute coronary syndrome.

10% of patients develop Q waves.

Within 24-48 hours of presentation the EKG frequently has deeply inverted T waves and markedly prolonged QT interval in both precordial and limb leads.

The QT interval prolongation will often return to normal in 2 days, but T wave changes can take weeks to months to improve.

Cardiac elevations are usually much lower than those seen with acute myocardial infarction.

It is suggested that enhanced sympathetic activity may play a role in transient myocardial dysfunction.

Recent studies have indicated that physical triggers are more common than emotional ones.

Physical triggers include exercise stress test, dobutamine stress test, electroconvulsive therapy, surgery, respiratory failure, seizures, CNS disorders, and acute critical illness.

Typical angiographic features include contractile abnormalities of the apex and the midportion of the left ventricle with relative bearing of the basal segments.

Complications are rare and prognosis is favorable, but recent studies suggest it has substantial morbidity and mortality.

It may be just as significant as acute coronary syndrome in the short term and in the long term it may be associated with persistent heart failure and in some cases a poor prognosis.

It is suggested the outcomes of the syndrome are worse in patients with medical illness as a trigger in comparison with an emotional stressor.

The international registry suggested 28% of patients have no trigger.

Patients have a reduced resting state functional connectivity among brain structures including: the amygdala, hippocampus, and cingulate regions of the limbic system that control parasympathetic and sympathetic functions.

Treatment is supportive.

Use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and beta blockers are used during left ventricular recovery.

ACE inhibitors or ARB agents improve one year survival impatiens prescribe such drugs on hospital discharge.

Medications are discontinued when left ventricular function recovery is complete.

Systemic anticoagulation considered during the first few days of the process until apical contractility recovers.

In patients with hemodynamic instability isotropic treatment, vasopressor support and intraarticular balloon counter pulsation may be utilized.

Rapid recovery is typical, with resolution of left ventricular dysfunction to normal within two weeks.

EKG changes usually resolve within 6 months.

Potential complications include congestive heart failure, left ventricle thrombus, left ventricular outflow obstruction, acute mitral valve regurgitation, and ventricular arrhythmias.

Ventricular arrhythmias seen in 18% of cases.

Hospital mortality about 1%.

Recurrence rate 3.5%.

Patient with takotsubo syndrome have more in hospital mortality and cardiovascular mobility than population controls (Auger N).