Sydenham’s chorea also known as “St. Vitus’ dance”.

Sydenham’s chorea also known as “St. Vitus’ dance”.

Sydenham’s chorea is a disorder characterized by rapid, uncoordinated jerking movements primarily affecting the face, hands and feet.

SC is an autoimmune disease that results from childhood infection with Group A beta-haemolytic Streptococcus.

It is reported to occur in 20–30% of people with acute rheumatic fever and is one of the major criteria for it, although it sometimes occurs in isolation.

Sydenham’s chorea is primarily seen in children.

The disease occurs typically a few weeks, but up to 6 months, after the acute infection.

The infection which may have been a simple sore throat.

Sydenham’s chorea is more common in females than males, and most cases affect children between 5 and 15 years of age.

The onset of SC in adults is comparatively rare, and the majority of the adult cases are recurrences following childhood Sydenham’s chorea.

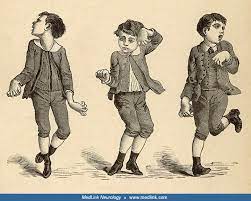

SC is characterized by the abrupt onset, sometimes within a few hours, of neurological symptoms, classically chorea, which are non-rhythmic, writhing or explosive involuntary movements.

Usually all four limbs are affected.

Raerely just one side of the body is affected (hemichorea).

Typically manifests as repeated wrist hyperextension, grimacing, lip pouting, fingers moving as if playing the piano, tongue fasciculations, motor impersistence (the “milkmaid sign”-grip strength fluctuates), or inability to sustain tongue protrusion or serpentine tongue, or eye closure.

There is usually a loss of fine motor control.

Speech is often affected as dysarthria, as is walking.

Legs will suddenly give way to one side, giving an irregular gait and the appearance of skipping or dancing.

Abnormal movements includes hypotonia, which may not become obvious until treatment is started to suppress the chorea.

In severe cases, the loss of tone and weakness predominate.

The severity of the condition can vary from just some instability on walking, to the extreme of being wholly unable to walk, talk, or eat.

SC movements cease during sleep.

SC is a neuropsychiatric disorder: along with motor problems there is classically emotional lability of mood swings, inappropriate mood, anxiety, and attention deficit.

Psychiatric manifestations of disease can precede the motor symptoms.

Non-neurologic manifestations of acute rheumatic fever may be present, namely carditis, arthritis, erythema marginatum, and subcutaneous nodules.

Differential diagnosis:

Cerebellar hemorrhage

Huntington disease

Leah-Nyhan syndrome

Lyme disease

Mitochondrial disease

Multiple system atrophy

Neuroacanthocytosis

Neuronal ceroid Lipofuscinoses

Olivopontocerebellar atrophy

Pediatric torticollis surgery

Wilson disease

Hyperthyroidism

SLE

Pregnancy

Drug intoxication

It is believed to be caused by an autoimmune response following infection by group A β-hemolytic streptococci.

Two cross-reactive streptococcal antigens have been identified, the M protein and N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosamine in infection leads to autoantibodies being produced against host tissues causing streptococcal related diseases including Sydenham’s chorea but also rheumatic heart disease and nephritic syndrome.

As with rheumatic fever, SC is seen more often in less affluent communities, whether in the developing world or in aboriginal communities in the global North.

High rates of impetigo are a marker for widespread streptococcal transmission.

Diagnosis is made by the typical acute onset in the weeks following a sore throat or other minor infection, plus evidence of inflammation with. raised CRP and/or ESR, and evidence of recent streptococcal infection.

To confirm recent streptococcal infection:

Throat culture

Anti-DNAse B titre (peaks at 8–12 weeks after infection)

Anti-streptolysin O titre (peaks at 3–5 weeks)

None of these tests are 100% reliable, particularly when the infection occurs months previously.

Further testing is directed more towards alternative diagnoses and other manifestations of rheumatic fever and include:

Echocardiography

Electroencephalography (EEG)

Lumbar puncture

Magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain.

Changes in caudate nucleus and putaminal enlargement have been described in some patients.

Management:

Management of SC is based on the following principles:

Eliminate the streptococcus

Treat the movement disorder

Immunosuppression

Prevention of relapses and further cardiac damage

Occupational therapy and physiotherapy is useful for maintaining function and muscle tone.

Treatment with sodium valproate is effective for controlling symptoms, but it does not speed up recovery.

Case reports of efficacy with carbamazepine and levetiracetam; other drugs tried include pimozide, clonidine, and phenobarbitone.

Immunosuppression is used inconsistently in Sydenham’s chorea.

One randomized controlled trial of steroids showed remission reduced to 54 days from 119 days.

Some improvement can be seen within a few days of IV steroids.

IVIG treatment may be efficacious.

A course of penicillin is usually given at diagnosis to definitively clear any remaining streptococci, without evidence that this is an effective treatment, as active infection is usually cleared by diagnosis.

Penicillin prophylaxis is essential to treat cardiac features of rheumatic fever, even if subclinical.

There are several historical case series reporting successful treatment of Sydenham’s chorea by inducing fever.

Prognosis:

Symptoms usually progress over the course of two weeks, then stabilize, and finally begin to improve.

Motor problems, including the presence of chorea, settle within an average of 2–3 months.

Recurrence, however, is seen in 16–40% of cases.

Recurrence is more likely with poor compliance with penicillin prophylaxis management.

Recurrences are sometimes associated with rise in ASO titre or other evidence of new streptococcal infection.

It can recur with pregnancy (chorea gravidorum), physical and emotional stress.

SC can recur up to 10 years after the initial episode: recurrence is usually only chorea.

Long-term consequence: 10% reported long-term tremor, neuropsychiatric abnormalities, especially obsessive-compulsive disorder but also attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, affective disorders, tic disorders, executive function disturbances, psychotic features, and language impairment.

Heart involvement improves in about a third of cases.