The stratum corneum is the outermost layer of the epidermis.

The stratum corneum is the outermost layer of the epidermis.

The stratum corneum consists of dead tissue, and it protects underlying tissue from infection, dehydration, chemicals, and mechanical stress.

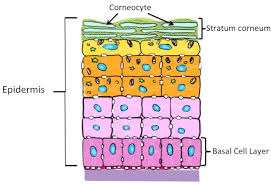

It is composed of 15–20 layers of flattened cells with no nuclei and cell organelles.

The stratum corneum contains 15 to 20 layers of corneocytes, with thickness between 10 and 40 μm.

Its properties include mechanical shear, impact resistance, water flux and hydration regulation, microbial proliferation and invasion regulation, initiation of inflammation through cytokine activation/dendritic cell activity, and selective permeability to exclude toxins, irritants, and allergens.

The cytoplasm of the stratum corneum cells shows filamentous keratin.

These corneocytes are embedded in a lipid matrix composed of ceramides, cholesterol, and fatty acids.

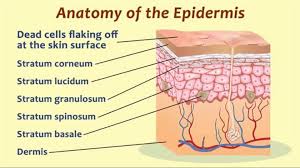

Desquamation, the process of cell shedding from the surface of the stratum corneum, is balanced by the proliferating keratinocytes that form in the stratum basale.

These cells migrate through the epidermis towards the surface in approximately fourteen days.

The stratum corneum comprises several levels of flattened corneocytes that are divided into two layers: the stratum disjunctum and stratum compactum.

The skin’s protective acid mantle and lipid barrier sits on top of the stratum disjunctum.

The stratum disjunctum is the uppermost and loosest layer of skin.

The stratum compactum is the comparatively deeper, more compacted and more cohesive part of the stratum corneum.

The corneocytes of the stratum disjunctum are larger, more rigid and more hydrophobic cells than those of the stratum compactum.

The first layer in the stratum compactum between them has limited swelling capacity and provides the stratum corneum’s barrier.

During the process whereby living keratinocytes are transformed into non-living corneocytes, the cell membrane is replaced by a layer of ceramides which become covalently linked to structural proteins, and contributes to the skin’s barrier function.

Modified cell desmosomes facilitate cell adhesion by linking adjacent cells within this epidermal layer.

When these complexes are degraded by proteases, it permits cells to be shed at the surface.

Desquamation and formation of the cornified envelope are required for the maintenance of skin homeostasis, and failure to correctly regulate these processes leads to skin disorders.

Stratum corneum contain a dense network of keratin.

Keratin is a protein that helps keep the skin hydrated by preventing water evaporation, and it can also absorb water, aiding in hydration.

The stratum corneum layer is responsible for the spring back activity or stretching properties of skin, as a weak glutenous protein bond pulls the skin back to its natural shape.

The thickness of the stratum corneum varies at body sites.

In the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet, and sometimes the knees, elbows, and knuckles, the SC layer is stabilized and built by the clear phase stratum lucidum which allows the cells to concentrate keratin and toughen them before they rise into a typically thicker, more cohesive stratum corneum.

The mechanical stress/strain causes this stratum lucidum phase in these regions requiring additional protection in order to grasp objects, resist abrasion or impact, and avoid injury.

At the site of the human forearm, there are about 1300 cells per cm2 per hour are shed.

The SC protects the internal structures of the body from external injury and bacterial invasion.

The inability to correctly maintain the skin barrier function due to the dysregulation of epidermal components can lead to skin disorders.

Hyperkeratosis is an increased thickness of the stratum corneum, and is an unspecific finding, seen in many skin conditions.