The skull base can be divided into the anterior, middle, and posterior compartments or fossae.

The skull base can be divided into the anterior, middle, and posterior compartments or fossae.

The skull base includes multiple bones, eleven pairs of cranial nerves and the olfactory nerves (CN I) pass through the inner table of the skull via 7 pairs of bony foramina and the cribriform plate (CN I).

The skull base also has multiple foramina that provide passage for vascular and other nerve elements.

Primary tumors may derive from the bone, paranasal sinuses, nasopharynx, inner ear, dura, cranial nerves, and brain.

Such lesions may cause symptoms through mass effect or through the invasion of local structures.

Metastatic tumors to the skull base and may also produce mass effect or invade adjacent tissue.

Skull base tumors include: meningiomas, pituitary tumors, sellar/parasellar tumors, vestibular and trigeminal schwannomas, esthesioneuroblastomas, chordomas, and chondrosarcomas.

Skull base tumors can be classified based on their tissue of origin, histology,, and anatomic location.

Even benign lesions may cause progressive deficits if located in an area where complete resection and growth cannot be controlled with medical or radiation therapy.

The lesions location often presents a significant challenge for safe surgical access.

Lesions may be proximateb or involvement of critical neural and vascular structures and the need to preserve the barrier between the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and the external environment.

Surgery is based on the involved area.

Brain exposing osteotomies, endoscopic surgery, infection prevention methods are improved techniques for reconstruction allow surgeons to perform biopsies and resections on most skull base masses.

Endonasal approaches to the skull base have significantly advanced abilities to treat tumors located there.

Radiosurgery is a useful tool in treating pathologic conditions at the skull base.

When craniotomy is undertaken, the goals of surgery are to minimize morbidity and to maximize the extent of tumor removal.

Osteomas are the most common primary tumor of the bone of the calvaria, and they are usually asymptomatic.

Osteomas are benign growths of dense cortical bone which often arise from the paranasal sinuses but may develop in the frontal bone, cranial vault, mastoid sinus, or mandible.

Osteomasgrow slowly and rarely expand internally to compress the brain.

Osteomas have been associated with hereditary syndromes: Gardner syndrome, an autosomal-dominant variant of familial adenomatous polyposis, which consists of multiple cranial osteomas, colonic polyposis, and soft-tissue tumors.

Chondromas are rare, slow-growing tumors that arise from the cartilaginous portion of bones formed by enchondral ossification.

In the cranial region, this includes the bones of the skull base and paranasal sinuses.

Progression to a malignant chondrosarcoma is rare.

Hemangiomas of the skull are benign vascular bone tumors composed of cavernous or capillary vascular channels.

Skull hemangiomas vary from small to very large and may be solitary or multiple.

They make up approximately 7% of skull tumors.

There are 2 types, the more common cavernous hemangioma and the more rare capillary hemangioma.

Dermoid and epidermoid tumors are benign lesions of the skull that develop in the cranial vault, paranasal sinuses, orbit, and petrous bone.

Dermoid and epidermoid tumors are

among the most common benign skull lesions in children.

These tumors usually arise in the midline, in the diploe of the bone, where they expand both the inner and outer tables of the skull.

Plasma cell tumors may present as solitary benign bone tumors called plasmacytomas

Solitary intracranial plasmacytoma of the skull base carries a dissemination rate of up to 100%, which is considerably higher than the rate associated with intracranial plasmacytoma of the dura or convexities.

Paragangliomas, such as glomus jugulare tumors, are benign neuroendocrine tumors that arise from chromaffin cells in the bony canals of temporal bone.

Paragangliomas are rare and represent 0.6% of all head and neck tumors; they present with a female-to-male ratio of 6:1.

Paragangliomas are locally invasive, and approximately 40% expand into the posterior cranial fossa, where they are identified as lesions of the cerebellopontine angle.

Paragangliomas rarely spread distally or involve the lymph nodes.

Larger tumors may cause symptoms related to cerebellar and brain stem compression.

Functional tumors represent the 1-3% of paragangliomas that produce catecholamines; the remainder are considered nonfunctional.

Paragangliomas that secrete catecholamines may cause a life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia or hypertensive emergency.

Other benign skull tumors:

aneurysmal bone cysts, osteoid osteoma, ossifying and nonossifying fibromas, and some variants of giant cell tumors.

Skull bone involvement is best demonstrated on CT scan with bone windows.

MRI can demonstrate intracranial extension.

Chondrosarcoma is a malignant cartilage tumor that originates from enchondral bones.

It is composed of cartilage-producing cells.

Chondrosarcoma makes up 0.15% of intracranial tumors and 6% of skull base tumors.

When it develops in the skull base, it usually arises in the parasellar area, cerebellopontine angle, or paranasal sinuses.

It may also arise in the clivus.

It is most common in men in the fourth decade of life.

Skull base lesions are thought to arise from the persistent islands of embryonal cartilage that occur near the cranial base synchondroses.

Chondrosarcomas can be divided into conventional, clear cell, mesenchymal, and dedifferentiated variants.

In the skull base, the conventional pattern is most common.

Low-grade classic chondrosarcomas generally carry a good prognosis.

They commonly present with cranial nerve palsies such as diplopia, hoarseness, dysphagia, facial dysesthesia, hearing loss, headache, and gait disturbance.

They are overall slow growing, but they are locally aggressive.

Chordoma is a low-grade malignancy that arises from tissue of the primitive notochord and in normal development becomes the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disk.

Approximately 40% of these tumors arise in the clivus with the remainder developing along the vertebral axis, most commonly in the sacrococcygeal region.

Chordomas may develop in persons of any age, but they manifest most commonly in persons aged 20-40 years.

A slight male predominance exists.

Clival chordoma is locally invasive and may extend into the middle fossa or brainstem.

Clival chordoma recurs despite surgical resection and radiotherapy and may destroy surrounding tissues, but it rarely metastasizes.

Chordomas are usually extradural in origin.

Approximately 10% of chordomas show more malignant histologic features, which are sometimes related to previous irradiation.

Osteogenic sarcoma is the most common malignant primary tumor of bone.

Osteogenic sarcoma develops most frequently in the second decade of life and may be associated with prior radiation, Paget disease, fibrous dysplasia, or chronic osteomyelitis.

Intracranial nerve sheath tumors grow at the skull base, where cranial nerves exit the brain stem and approach the bony foramina.

Intracranial nerve sheath tumors develop sporadically or as part of the genetic syndromes neurofibromatosis-1 (NF-1) and neurofibromatosis-2 (NF-2).

Sporadic cases generally manifest as a single lesion, whereas multiple tumors present as part of a hereditary syndrome.

The most common intracranial nerve sheath tumors are schwannomas.

These lesions arise almost exclusively from sensory nerves.

The most common is the vestibular schwannoma, sometimes called acoustic neuroma.

Schwannomas and neurofibromas are well encapsulated and can usually be completely resected, but the involved nerve must often be sacrificed.

Vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuroma, acoustic neurofibroma) is a benign tumor that arises from Schwann cells of the vestibular branch of the VIII nerve in more than 90% of cases; less than 10% arise from the cochlear branch of VIII.

Vestibular schwannoma accounts for 5-10% of all intracranial tumors and is the most common tumor of the cerebellopontine angle.

The peak age for tumor occurrence is between age 40 and 60 years, and they are twice as common in women as in men.

Bilateral tumors occur in less than 5% of patients and, when present, are diagnostic for NF-2.

Vestibular schwannomas grow slowly into the internal auditory meatus and the cerebellopontine angle, displacing the adjacent cerebellum, pons, or cranial nerves (usually V and VII).

Because they grow slowly, many tumors are large and even cystic before they become symptomatic.

The growth rate may increase during pregnancy.

Trigeminal schwannomas account for less than 8% of intracranial schwannomas and less than 0.4% of all intracranial tumors.

Trigeminal schwannomas originate within the ganglion, nerve root, or 1 of the 3 divisions of the trigeminal nerve.

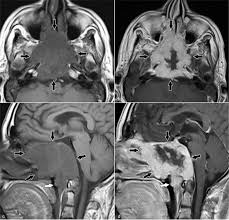

Diagnosis trigeminal schwannomas established with MRI.

The differential diagnosis includes meningioma, vestibular schwannoma, epidermoid lesions, and primary bone tumors of the skull base.

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are a rare and aggressive type of spindle cell tumor, affecting patients primarily aged 20-50 years.

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors originate from perineural or Schwann cells of the peripheral nerve sheath.

Meningiomas arise from meningothelial cells, which are most common in the arachnoid villi, and they comprise 22% of all intracranial tumors.

They account for 3-12% of cerebellopontine angle tumors.

Most meningiomas are diagnosed in the sixth or seventh decades of life.

Meningiomas are more common in women, with a female-to-male ratio of 3-2:1.

Five to fifteen percent of patients with meningiomas have multiple meningiomas especially those with NF-2.

More than 90% of tumors are intracranial and 10% intraspinal.

Radiation exposure is the only proven nongenetic risk factor for meningioma formation

Radiation-induced meningiomas usually develop over the cerebral convexities rather than at the skull base.

Trauma has been suggested as a risk factor for meningioma formation which can present at the skull base.

Familial meningiomas develop with NF-2, and patients with NF-2 are at increased risk for meningiomas as well as vestibular schwannomas.

Deletion of the c-sis protooncogene (a polypeptide homologous with platelet-derived growth factor [PDGF] receptor) on chromosome 22 has been linked to meningioma formation.

Abnormalities in other chromosomes suggest that several oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes are involved in meningioma formation.

Most meningiomas are nodular and compress adjacent structures. Occasionally, they are distributed in sheathlike formations (meningioma en plaque).

This pattern is especially common in skull base meningiomas of the sphenoid ridge.

All meningiomas are encapsulated and attach to the dura, from which they derive their blood supply.

Hyperostosis of the underlying bone is common and can be appreciated radiographically.

The WHO grading system classifies meningiomas as typical (or benign), atypical, or malignant based on cellularity, cytologic atypia, mitosis, and necrosis.

Malignant meningiomas are rare but aggressive, and about half metastasize systemically, usually in bone, liver, or lung.

Benign meningiomas recur in about 7-20% of patients, atypical variants recur in 29-40% of patients, and anaplastic tumors recur in 50-78% of patients.

Brain invasion may develop with all 3 histological grades of meningioma.

Brain invasion connotes a greater likelihood of recurrence but does not indicate a truly malignant histologic pattern.

Nevertheless, an elevated proliferation index (>5%) does predict a poor outcome.

Clear-cell meningiomas make up 0.2-0.81% of all meningiomas and are often more aggressive than more common varieties, with frequent recurrence and CNS metastasis.

Secretory meningiomas secrete vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and are associated with extensive edema.

Hemangiopericytoma is a rare lesion that comprises 0.4% of primary CNS tumors.

It is a richly vascular and highly cellular tumor that is almost invariably associated with the meninges.

They are a type of sarcoma that derives from pericytes that surround blood vessels.

They often appear much like meningiomas on imaging.

Tumors of the skull base can also be described on the basis of their most common presenting location.

Tumor location often dictates the presenting signs and symptoms.

The skull base can be divided into the anterior, middle and posterior fossae.

This distinction helps the surgeon choose which surgical approach offers the greatest opportunity for complete tumor removal with minimal potential for neurologic injury.

The tumors of the anterior cranial fossa may be malignant or benign.

The malignant tumors in this group include tumors that arise in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, inverted papilloma, lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Other malignant tumors that develop in this region include orbital gliomas and other orbital tumors, rhabdomyosarcomas, and osteogenic sarcomas.

The benign tumors that develop specifically in the anterior skull base include ossifying fibromas.

Esthesioneuroblastoma, (olfactory neuroblastoma), is a very rare tumor.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma may enter the intracranial space by extension through the cribriform plate.

Tumors of the middle cranial base are usually benign.

These tumors include pituitary adenomas, craniopharyngiomas, cavernous sinus meningiomas, temporal bone tumors, cholesteatomas, and enchondromas.

Malignant tumors in this area may arise primarily: osteogenic sarcoma or secondarily through local invasion or hematologic spread from distant sites.

Tumors unique to the posterior cranial fossa include both benign and malignant lesions.

Benign tumors involving the posterior skull base include meningiomas of the foramen magnum, clivus and cerebellopontine angle, epidermoids, dermoids, chondromas, and chordomas.

Malignant tumors that involve the skull base are less common than their benign counterparts.

Skull base metastases usually arise from a prostate, breast, lung, or head and neck primary lesion or from lymphoma.

The cardinal sign of metastatic skull base invasion is cranial neuropathy.

Skull base metastases are often painless, localized cranial or facial pain at the site of tumor invasion may be a symptom.

MRI scans can reveal even small skull base metastases.

Several malignant tumors involve the base of the skull by direct extension: squamous cell carcinoma of the nasal sinuses and temporal bone, adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands, esthesioneuroblastoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Skull base tumors are relatively rare.

Meningiomas constitute approximately 22% of primary intracranial tumors.

If autopsy data are included, the overall incidence of meningiomas is 2.3-5.5 cases per 100,000 persons.

As with meningiomas in other regions, skull base meningiomas demonstrate a female predominance, with a female-to-male ratio as high as 3:1.

Approximately 15% of meningiomas grow along the sphenoid ridge, with 10% developing in the posterior cranial fossa and 5% in the olfactory groove.

Meningiomas of the floor of the middle fossa are uncommon and tend to grow quite large before diagnosis.

The clinical presentation of meningiomas is based on the structures adjacent to the lesion.

Lesions at the skull base present with cranial neuropathies.

Slow tumor growth may allow the lesion to grow large before coming to clinical attention.

Schwannomas constitute less than 10% of all primary intracranial tumors.

Schwannomas of the vestibular nerve are the most common neoplasms that involve the temporal bone and represent 75% of tumors that occupy the cerebellopontine angle cistern.

Chondrosarcomas constitute approximately 0.1% of all intracranial tumors.

Half of these develop at the cranial base.

Chordomas also constitute approximately 0.1% of all intracranial tumors.

Forty percent of chordomas develop at the skull base.

Skull base metastases, not including direct extension, occur in 4% of cancer patients.

Skull base tumors vary in presentation directly due to the location of the lesion and the growth rate.

Osteomas grow slowly and rarely expand internally to compress the brain; therefore, they are usually asymptomatic.

When osteoma symptoms manifest, they may include local pain, headache, or recurrent sinusitis.

Chondromas of the parasellar region or cerebellopontine angle often manifest as cranial nerve palsies, nasal obstruction, shortness of breath, and hoarseness.

Hemangiomas receive blood supply from the scalp or meningeal vessels, and periosteal involvement may produce headaches.

Dermoid and epidermoid tumors of the skull usually arise in the midline, in the diploe of the bone, where they expand both the inner and outer tables of the skull.

Paragangliomas are slowly growing hypervascular lesions that usually present with gradual hearing loss, unilateral pulsatile tinnitus, and lower cranial nerve palsies.

Larger paraganglioma tumors may cause symptoms related to cerebellar and brain stem compression.

Functional tumors represent the 1-3% of paragangliomas that produce catecholamines; the remainder are considered nonfunctional.

The functional tumors may cause hypertensive emergency or cardiac arrhythmias due to catecholamine release.

The cardinal sign of metastatic skull base invasion is cranial neuropathy, which is typically sudden in onset.

Although skull base metastases are often painless, localized cranial or facial pain at the site of tumor invasion may be a symptom.

Direct extension of malignant tumors to the skull base, may tumors affect cranial nerve function, but unlike metastases, they often also cause pain.

Chondrosarcomas and chordomas of the skull base may present with similar symptoms, with headache and diplopia, due to cranial nerve palsies, being are most common, occurring in approximately 60-65% of patients.

Chondrosarcoma has a more favorable prognosis than chordoma.

Vestibular schwannoma, if untreated progressive unilateral hearing loss develops in nearly all patients.

Hearing loss is often preceded by difficulty with speech discrimination, especially when the patient is talking on the telephone.

Tinnitus (70%) and unsteady gait (70%) are also common.

Further tumor growth can cause facial numbness (30%) or, less often, facial weakness, loss of taste, and otalgia due to encroachment on the trigeminal and facial nerves.

Larger tumors grow into the cerebellopontine angle, causing headache, nausea, vomiting, diplopia, and ataxia or increased intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus.

Other signs include nystagmus and cerebellar ataxia.

The constellation of late symptoms can develop with any mass in the cerebellopontine angle; however, only vestibular schwannomas present with initial symptoms of tinnitus or hearing dysfunction.

Nearly all patients develop numbness and pain in the trigeminal distribution, in trigeminal schwannoma, and about 40% have some weakness in the muscles of mastication.

True trigeminal neuralgia is uncommon.

Extension of the tumor into the posterior fossa is associated with seventh and eighth nerve dysfunction and cerebellar and pyramidal tract signs.

Benign tumors of the anterior cranial fossa include meningiomas.

These tumors have slow growth rate, and are clinically recognized only after they are very large and have caused significant mass effect on the frontal lobes: may result in personality changes.

Tumors of the posterior cranial fossa:

Cerebellopontine angle meningiomas often present with hearing loss and facial pain or numbness.

By the time eighth nerve dysfunction is evident, the tumor is usually large.

Foramen magnum meningiomas cause pain, gait difficulties, and wasting of the hand muscles, atypical rotating paralysis, with sequential weakness beginning in the ipsilateral upper extremity and progressing to involve the ipsilateral lower extremity, contralateral lower extremity, and ipsilateral upper extremity, in that order.

General imaging studies for assessment of skull base tumors include:

CT scan of the brain

Brain MRI with and without gadolinium is the best study to evaluate soft tissue masses and structures.

Cerebral angiography is beneficial if the tumor encroaches on the carotid or other major intracranial arteries or a major venous sinus.

Cerebral angiography is used to assess whether arteries and venous sinuses are patent.

In the case of meningioma and other vascular tumors, N angiographic embolization of appropriate feeding vessels can decrease blood loss during operative resection and contribute to the ease of tumor removal.

MR arteriography and venography may also be used to assess the patency of arterial and venous structures.

Tests are used to formally evaluate cranial nerve function, visual field evaluation, audiography, or swallowing.

For vestibular schwannoma, hearing function, brainstem auditory evoked potentials, caloric stimulation with electronystagmography, and audiometry are performed.

Large vessel compromise due to tumor involvement can be documented preoperatively with angiography to allow for adequate presurgical planning.

Osteoma: Diagnosis is based on the radiographic appearance.

CT scanning, the lesion appears as a circumscribed homogeneous bony density.

Chondromas are radiographically are best characterized by CT scanning; these tumors appear as lytic lesions with sharp margins and erosion of surrounding bone.

Its stippled calcifications within the lesion helps distinguish it from a metastasis or chordoma.

Hemangioma skull radiographs may demonstrate a circular lucency with trabeculations, and CT scanning demonstrates a nonenhancing hypodense lesion.

Dermoid and epidermoid tumors of the skull have rounded or ovoid lytic lesions with sharp sclerotic margins.

On CT scans, these lesions are nonenhancing and hypodense and involve all 3 bone layers.

MRI demonstrates a low-intensity lesion on T1 and a high-intensity lesion on T2.

Paragangliomas: MRI and magnetic resonance (MR) angiography characterize paragangliomas because these modalities usually reveal their extensive vascularity, meriting preoperative embolization in many cases.

Fibrous sarcoma is a soft tissue tumor that arises from bone, periosteum, scalp, or dura.

Fibrous sarcoma is often accompanied by bony destruction, showing a regular but discrete lytic radiographic picture.

Vestibular schwannoma show tumor enhancement on MRI at its origin in the internal auditory canal and distinguishes it from a meningioma.

Trigeminal schwannoma: Diagnosis is best established with MRI.

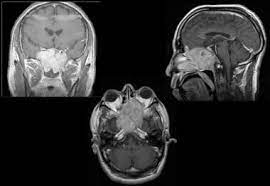

Imaging of skull base meningiomas includes CT scanning, MRI, and sometimes angiography.

On nonenhanced CT scans, the tumor is isodense or slightly hyperdense compared with the brain.

The meninges mass is generally smooth and sometimes lobulated, and calcifications are often appreciated.

Contrast enhancement is strong and margins are distinct, and the tumor’s dural base can usually be appreciated.

Hyperostosis of the underlying bone is common and can be appreciated in the immediate adjacent bone is seen in 25% of patients.

On MRI, the tumor is isointense (65%) or hypointense (35%) when compared with normal brain on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted imaging.

Intense, homogeneous gadolinium enhancement is visible in meningiomas.

MRI is the best modality to define the relationship between the tumor and surrounding structures.

Atypical radiographic features such as cysts, hemorrhage, and central necrosis, which mimic features of glioma, are visible in about 15% of meningiomas.

Malignant meningiomas commonly demonstrate bone destruction, necrosis, irregular enhancement, and extensive edema.

MRI may demonstrate the rare cases of direct brain invasion by tumor.

On angiograms, skull base meningiomas are hypervascular, generally being fed by blood vessels from the external carotid artery.

Hemangiopericytoma

Gadolinium-enhanced MRI best characterizes these lesions.

CT scanning may help differentiate hemangiopericytoma from a meningioma by demonstrating local osteolysis, rather than the hyperostosis that may be seen with meningioma.

Angiography can demonstrate the tumor’s vascularity, and embolization can be a helpful adjunct prior to surgical intervention.

Malignant neoplasms of the skull base are divided the lesions into those that involve the anterior skull base, the clivus, or the lateral skull base.

Tissue diagnosis is established via a minimally invasive biopsy.

Extensive resection of malignant lesions of the anterior skull base is performed through an intracranial, extracranial, or combined approach.

The 2 most common intracranial surgical approaches are the orbitozygomatic craniotomy and the bifrontal craniotomy.

Bifrontal craniotomy provides access to the undersurface of the frontal lobe, allowing an extradural subfrontal approach to the floor of the anterior fossa.

Clivus

Minimally invasive methods to obtain a tissue diagnosis may be appropriate for malignant tumors that involve the clivus: endoscopic biopsy has become a favored approach to achieve this goal.

Meticulous dural closure and cranial reconstruction are the prevent the most common complications, which include cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak and infection.

Radiation therapy has been successfully applied as both a primary and an adjunctive modality in the treatment of benign and malignant skull base neoplasms.

Among radiosurgical modalities, gamma knife radiosurgery (GKRS) technology is the most commonly used.

GKRS has been well established in the treatment of meningiomas smaller than 3 cm in diameter.

Of patients treated with GKRS 70% of the lesions were located at the skull base, with an average tumor volume of 7.3 cm3:, 94% of tumors remained stable or decreased in size.

Treatment-related complications occurred in 8% of the patients.

In vestibular schwannoma 94% tumor control rate using GKRS.

Subtotal resection followed by GKRS has proven to be a viable treatment option for large vestibular schwannomas: good tumor growth control and facial nerve function preservation, plus the possibility of preserving serviceable hearing and the low number of complications.

Larger tumors can be treated with initial microsurgical resection, focusing on facial nerve preservation and leaving residual tumor if the facial nerve was determined to be at risk, while smaller tumors and postmicrosurgical tumor regrowth were treated with GKRS.

Microsurgery shows that facial nerve–sparing microsurgery provides good tumor control with excellent facial nerve preservation rates (97% of patients).

In a review of radiosurgical treatment of pituitary adenomas: control of tumor growth in 92-100% of tumors.

Endocrine cure rates of 0-96% were reported in cases of growth hormone-secreting adenomas and 0-84% in prolactinomas.

GKRS is the best option in the treatment of small, medically refractory lesions in surgically inaccessible locations.

A significant complication related to radiotherapy or radiosurgery is radiation-induced necrosis.

Radiation necrosis may mimic tumor recurrence and can produce significant mass effect through edema.

Positron emission tomography (PET) can be used to help distinguish radiation necrosis from recurrent tumor.

Endoscopic neurosurgery offers a minimally invasive route to specific lesions and is increasingly being implemented as a tool for the biopsy and removal of these lesions.

The role of endoscopy in accessing and resecting tumors of the skull base continue to expand and outcomes after endoscopic surgery continue to improve.

The most common endoscopic skull base procedures include the transsphenoidal approach to sellar lesions.

Advantages of endoscopic skull base surgery include its ability to access areas that a conventional microscope cannot, better visualization with the panoramic endoscopic view, ability to

can gain access to many lesions of the skull base with minimal manipulation of neurovascular structures and decreased brain retraction.

Disadvantages of endoscopic surgery compared with more traditional minimally invasive techniques include visualization, difficulty due to the loss of binocular vision, and a moderate risk of CSF leak.

Either endoscopic surgery operating in an area where access is limited creates disadvantages in itself, such as limited visualization of the lesion, difficulty inserting and using certain instruments, and difficulty controlling bleeding in the event of a hemorrhagic complication.

Endoscopic approaches to anterior skull base lesions involve a craniotomy, such as the frontal, bifrontal, expanded bifrontal, frontotemporal orbitozygomatic, and transbasal approaches.

Such surgical approaches carry risk of morbidity: dissection of the temporalis muscle, risk to the frontalis branch of the facial nerve, and creation of an epidural space.

The endoscopic endonasal approach is the standard of care because it provides minimally invasive access to a large portion of the skull base, including anterior and middle cranial fossae and sellae and suprasellar and parasellar regions, and it has been associated with lower surgical morbidity and shorter length of hospitalization.

The transnasal approach allows surgeons to perform transcribriform, transclival, and transodontoid approaches to target lesions of the olfactory groove, the lower two thirds of the clivus, and the odontoid-cervico-medullary junction, respectively.

This approach is the most commonly used and can be employed in the transsellar, transtuberculum, transplanum, transclival, and transcavernous approaches.

These approaches permit access to lesions of the anterior fossa, orbital apex, and cavernous sinus, respectively.

Endoscopic surgery of the skull base provides a minimally invasive alternative to open surgery for many specific lesions.

Approaches to the anterior skull base can be divided into intracranial, extracranial, and combined approaches.

Complications of skull base surgery can be classified into neurologic, wound related, cosmetic, and perioperative.

Neurologic complications include cranial nerve injuries and injury that affects the CNS, based on the location of the tumor.

Stretch or traction injury, thermal injury due to electrocautery, or sharp transection of nerves can occur.

Cranial nerves displaced by or under tension from tumor growth are most vulnerable, but any cranial nerve in or near the operative field is at risk.

Concurrent injury to multiple cranial nerves can be devastating.

Injury to the lower cranial nerves (IX, X, XI, XII) can produce swallowing difficulties and can place the patient at risk for aspiration and pneumonia.

Operative morbidities that affect the CNS:

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak

Pneumocephalus

Intracranial hemorrhage

Hydrocephalus

Cerebral contusion

Meningitis

Cerebral edema

Stroke

Epidural abscess

Seizures

Diabetes insipidus

Altered mental status

Anosmia

CSF leaks may occur if the dura is violated by surgery or by tumor invasion.

Complications associated with CSF leakage include poor wound healing and meningitis.

Wound complications include:

Cellulitis

Infected cranial bone flap or osteomyelitis

Oronasal fistula

Necrosis of a pericranial flap

Encephalocele

Crusting of the nasal cavity

Cosmetic complications include enophthalmos, facial scar, burr hole-related scalp depression, and ocular dystopia.

Cosmetic deformity occurs more with anterior surgical approaches because it may involve the orbit or face.

Intraoperative blood loss may be significant because of the extensive dissection that is sometimes necessary for approaches to the skull base.

Benign tumors (meningiomas), can be resected with minimal mortality and acceptable morbidity.

In a series of skull base meningiomas by, the rate of total excision was 60%, the postoperative mortality rate was 15%, and the postoperative major morbidity rate was 16%.

Sixty percent of patients developed a new cranial nerve deficit, and 3% of the patients had a recurrence.