Third most common tumor of the central nervous system after gliomas and meningiomas.

Third most common tumor of the central nervous system after gliomas and meningiomas.

The most common neoplasms of the seller region, and include functioning, tumors, which secrete, pituitary hormones autonomously, and non-functioning tumors, which are not associated with hormonal excess.

Pituitary tumors are monoclonal tumors: either macroadenomas 108mm or greater in diameter, or micro adenomas, less than 10 mm in greatest diameter.

Responsible for 15% of clinically diagnosed intracranial neoplasms.

10% of the population has a pituitary adenoma seen on imaging studies or at autopsy.

Approximately 99.9% of these on micro adenomas.

Approximately 40% of incidental pituitary adenomas identified during autopsy show prolactin positive immunostaining.

Among incidentally identified pituitary adenomas,macroadenoma are more likely than microadenoma to enlarge during follow up.

Oligomenorrhea occurs in approximately 93% of women with prolactin secreting pituitary adenomas, and approximately 85% of these women have galactorrhea.

Hypogonadism is a consequence of hyperprolactinemia, and may cause infertility in both women and men.

In women hyperprolactinemia may cause a shorter luteal phase, contributing to infertility.

People with hyperprolactinemia have skeletal fragility, increased rates of fractures, which are most likely due to hypogonadism secondary to hyperprolactemia.

30 % of people with hyperprolactinemia have vertebral fractures.

Clinically evident pituitary adenoma are present in 1 in 1100 individuals in the general population, of these, 48% are macro adenomas.

The majority of incidentally, discovered pituitary microadenomas do not grow, or cause symptoms over time.

Lesions are often undiagnosed, and small pituitary tumors have an estimated prevalence of 16.7% with 14.4% in autopsy studies and 22.5% in radiologic studies.

Usually benign slow growing tumors.

Can cause symptoms by excess hormone release, mass effects, or both.

Patients with non-functioning, pituitary adenomas may present with mass effect symptoms, including: visual field defects, headache, and anterior hypo pituitarism.

In contrast, arginine vasopressin deficiency is present only in patients with infiltrative or suprasellar lesions.

Between four and 10% of patients present with pituitary apoplexy, consisting of hemorrhagic infarction of the tumor, with headache of acute onset, visual field effects, and ophthalmoplegia.

Microadenomas that are clinically non-functioning, are unlikely to cause mass effect and may be detected during brain imaging studies performed for other reasons.

Pituitary adenomas that do not produce hormones account for approximately 30% of adenomas that come to clinical attention and cause symptoms because of mass effect, and they arise from cells of the gonadotrophin lineage in about 80% of patients.

Distinct hypersecretory syndromes depend on the cell of origin: corticotropin secreting adenomas result in Cushing’s disease, growth hormone secreting adenomas result in acromegaly, prolactin secreting adenomas result in hyperprolactinemia, and thyrotropin secreting adenomas resulting hyperyhyroidism.

Gonadotrophin adenomas, are typically nonsecreting, but lead to hypogonadism and often manifest as a sellar mass.

Prolactinomas are the most common secretory tumor accounting for 60% of all pituitary adenomas and more than 75% of pituitary adenomas in women.

Prolactinomas arise from cells of lactotrophic lineage.

Micro prolactinomas have a female: male ratio of 20:1, are usually stable and slow growing, with continue growth after diagnosis in less than 15% of cases.

Women who develop a prolactin secreting, pituitary adenoma are diagnosed at a younger age than men.

Most patients with a pituitary mass and a serum prolactin level exceeding 150 ng/ millimeter are found to have a prolactinoma.

Macroprolactinomas account for 9 to 27% of all prolactinomas in women and 50 to 75% in men.

Hyperprolactinemia is caused mainly by pregnancy, prolactinomas, medications, chest wall injury, functional or mechanical interruption of the pituitary stalk dopamine transport.

Prolactin levels are elevated in approximately 30% of patients with acromegaly.

Most non-secreting adenomas are of gonadotrophic lineage and express differentiated hormone products and cell specific transcription factors but are not associated with systemic syndrome phenotypes:null-cell adenomas express no hormone gene product.

Non-secreting adenomas may be unrecognized for years, and are diagnosed primarily because of local mass effects or hypogonadism are noted to be present incidentally.

Silent tumors express non-secreted cortotropin or growth hormone account for up to 20% of non-secreting tumors.

Growth hormone secreting pituitary adenomas account for approximately 12% of pituitary adenomas, and arise from cells of somatotrophic lineage, and 70% of somatotropinomas are macro adenomas at diagnosis.

They are usually resected after nonsecreting macroadenoma has been diagnosed with the diagnosis confirmed histologically.

Thyrotropin secreting, pituitary adenomas account for about 1% of pituitary adenomas and arise from cells of thyroroph lineage: 75% of these tumors are macroadenomas.

Patients with thyrotropinomas present with signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism in 75% of cases, goiter in 55%, atrial fibrillation/heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction in 11%, and visual field effects in 25%.

Central hyperthyroidism, with excessive thyroid hormone secretion, secondary to thyro gift card tropin, secreted from a pituitary tumor is characterized by an elevated thyroxine level and elevated or inappropriately normal thyrotropin levels.

The presence of an elevated serum free thyroxine with high or normal thyroid levels is nearly 100% sensitive for a thyroid tropinoma.

Silent tumors can grow aggressively without features of hypercortisolism or acromegaly, and may be indistinguishable from those of secretary adenomas.

Corticotropin secreting pituitary adenomas account for 4% of pituitary adenomas and arise from cells of corticotrophin lineage.

Corticotropin secreting pituitary adenomas are substantially more common in women (8:1).

Patients with corticotropinomas present with Cushing disease, characterized by central adiposity, facial rounding, plethora in 72 to 90% of cases, hypertension in 60% of cases, dyslipidemia in 70% of cases, diabetes in 40%, hypogonadism in 75%, proximal muscle weakness in 60% of cases, reddish, purple striae, osteoporosis 60% of cases, and nephrolithiasis 20 to 50% of cases.

Cognitive dysfunction and psychiatric manifestations, such as anxiety, depression, insomnia, and psychosis occur in approximately 50% of patients.

90% of patients with corticotropinomas are microadenomas and present with signs and symptoms of cortisol excess.

Silent corticotroph that underwent surgical treatment have a 31% recurrent during a follow up of more than five years.

Optic chiasmal compression causes gradual but progressive deficits in vision, and about 2/3 of patients have decreased gonadotropin levels and hypogonadism.

Rarely, circulating gonadotropin levels are elevated and result in ovarian hyperstimulation or increased testicular volume: paradoxically high gonadotropin levels more commonly down regulate the gonadal axis.

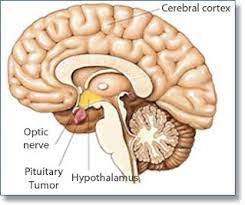

Macroadenomas can cause mass effect: visual field defects, headache, or hypopituitaryism.

People with hypopituitarism due to pituitary adenomas have a twofold increase in all-cause mortality compared with the general population.

Acromegaly in older studies was associated with a twofold increase in all-cause mortality, but in more recent studies there is better biochemical control of the disease.

Acromegaly is characterized by facial and cranial changes, such as frontal bossing, large nose and lips, increased dental spacing, and prognathism, and acral enlargement in 95%, headache in 60% of patients, arthropathy in 70% of patients, hyperhidrosis in 65% of patients and compressed or collapsed vertebrae in 50% of patients, diabetes, or pre-diabetes in 50% of patients, hypertension in 35%, cardiomyopathy leading to congestive heart failure in 10%, valvular heart disease up to 30%, sleep apnea 65%, carpal tunnel syndrome 64% and hyperprolactinemia 30%.

Cushing’s disease has been associated with a threefold increase in all-cause mortality.

About 10% of patients with non-secreting adenomas present with pituitary apoplexy of abrupt retro-orbital pain, altered consciousness, ophthalmoplegia, and loss of vision from

In African-Americans, pituitary adenomas account for one fifth of primary central nervous system neoplasms.

14.7 individuals per 100,000 population are diagnosed annually.

Autopsy studies reveal an incidence as high as 25% of the population.

Prevalence has increased to 115 cases per hundred thousand population as a result of enhanced awareness and improved diagnostic imaging and hormone assays.

Approximately 20% of normal adults have incidental pituitary lesions measuring 3 mm or more in diameter, on MRI or high resolution CT scans, and these are usually silent adenomas.

Tumors measuring 10 mm or less in diameter are considered microadenomas: macroadenomas are tumors larger than 10 mm.

Macroacenomss may impinge on vascular and neural structures with visual field defects, including bitemporal hemianopsia and decreased acuity, and headaches.

Usually in adults with peak incidence 30-50’s.

Most lesions are isolated, but about 3% associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN type1)

Most often manifest secondary to hypersecretion, hypopituitarism, or mass effect.

Pituitary adenomas may occur in association with genetic syndromes

Silent lesions and lesions which are hormone negative likely to come to clinical attention at a later date than lesions associated with hormonal abnormalities.

With tumors that secrete hormones, patients may present with signs and symptoms of mass effect and/or with symptoms of hormonal excess.

Most common cause of hyperpituitarism.

May occur in associations with several genetic syndromes: multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, the McCune-Albright syndrome.

Rarely associated with familial predisposition with germline mutations in the AIP gene.

Is part of the Carney complex.

May be associated with hormone excess or it may be silent.

Functional and silent forms usually composed of a single cell type and a single predominant type of hormone.

Classified on the basis of hormones produced.

Some lesions can produce 2 or more hormones.

Hormone negative lesions exist with negative immunohistochemical tests.

Hormone negative and silent lesions may produce hypopituitarism as the mass may encroach and destroy adjacent anterior pituitary tissue.

Majority of lesions are monoclonal in origin.

Mutations of RAS oncogene and overexpression of c-MYC oncogene may be present in aggressive or advanced lesions.

The common lesion is a well circumscribed process that may be confined to the sella turcica.

As lesions progress in size they may extend superiorly from the sella to the suprasellar region where they can compress the optic chiasma and some of the cranial nerves.

Larger lesions can erode the sella and the anterior clinoid processes.

Large lesions can extend into the cavernous and sphenoid sinuses.

In about 30% of cases the lesions are not encapsulated and can erode into adjacent bone, dura and even the brain, and are known associated invasive adenomas.

Evaluation of a pituitary mass includes MRI localization.

As tumors enlarge areas of necrosis and hemorrhage can appear.

Histologically composed of uniform, polygonal cells in sheets or cords, sparse connective tissue, modest mitoses, with basophilic, acidophilic or chromophobic cytoplasm depending upon the product secreted from the cells.

Functional status of the lesion can not be ascertained from its histologic features.

TREATMENT:

Transphenoidal pituitary surgery is the first line of therapy for all pituitary adenomas that require treatment, with the exception of prolactinoma.

Prolactinomas are generally treated medically.

Standard treatment of nonfunctioning lesion is transsphenoidal surgery.

Patients with Cushing diseas or acromegaly, requiresurgery.

Some patients with small non-functioning, pituitary tumors that do not reduce vision and are stable in size can be followed with serial MRIs.

Transphenoidal surgery enables the surgeon, visualize the sella, using an endoscope or operating microscope, but less commonly a craniotomy is required to resect a large, invasive, and or aggressive tumor.

Regrowth of tumor remnant after resection occurs in 38-95% of cases in patients who have incomplete resections.

Approximately 30% of surgically resected adenomas persist or progress for up to four decades or even longer, with subsequent local invasion and increased percentage is positive Cells for Ki-67.

In patients with recurrent tumors treatment options include reoperation for visual problems with opticochiasmatic decompression, stereo tactic radio surgery and fractionated radiation therapy.

Complete resection of nonsecreting macroadenoma is achieved in approximately 65% of patients, and comes with visual function restored in up to 80% of patients and hypopituitarism, when present reversed in approximately 50%.

Pituitary carcinomas are exceedingly rare, accounting for less than 0.5% of pituitary tumors.

A prolactin level of more than 250 ng/mL is usually diagnostic of a macropractinoma, and the tumor mess usually correlates with serum prolactin level.

Persistent elevated prolactin levels suppress gonadotropin, leading to amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, short luteal phase associated with infertility in men and low libido, impotence, oligospermia or azoospermia in men.

About 50% of women and 35% of men have galactorrhea and both suffer with reduced bone density, often associated with sex steroid hormone deficiency and an increased risk of vertebral fractures.

Diagnosis and evaluation:

Patients with possible pituitary adenomas should undergo hormone testing and pituitary imaging.

A pituitary protocol MRI can delineate the size and imaging characteristics of sellar masses.

Serum prolactin level should be measured to evaluate for prolactinoma.

Approximately 99% of patients with serum prolactin levels greater than 250 µg per liter have prolactinoma.

Serum IGF-1 is measured to detect growth hormone excess.

Serum measures of growth hormone levels are of limited value because growth hormone a short half-life and growth hormone is pulsatile.

Cushing disease – late night salivary cortisol, 24 hour urinary free cortisol, and the 1 mg dexamethasone suppression test can establish the presence of hypercortisolism.

An elevated late night salivary cortisol test result is 95.8% sensitive and 93.4% specific, an elevated urinary free cortisol test result is 94% sensitive and 93% specific, and a cortisol threshold of 1.8 µg per deciliter or higher during the dexamethasone suppression test is 98.6% sensitive and 90.6% specific for Cushing disease.

Once hypercortisolism is established, a plasma corticotropin level should be done to distinguish between corticotropin dependent etologies and corticotropin independent causes of Cushing syndrome.

Treatment: for patients with endogenous Cushing syndrome, the primary aim of treatment is complete resection of the underlying tumor.

Management of pituitary adenoma includes transphenoidal surgical resection, radiation, and medical therapy.

Transphenoidal pituitary surgery with selective adrenomectomy is the primary therapy for Cushing disease.

Surgery is generally an indicated process for pituitary adenoma masses that are 10 mm or more in diameter and those that have extrasellar extension or central compressor features, as well as for persistent tumor growth, especially if vision is compromised or threatened.

Patients with a non-functioning pituitary adenoma should be referred for surgery if there is a mass effect, tumor size greater than 10 mm in diameter, compression of the optic chasm.

Postoperatively, vision improves in 70-90% of patients and recovery of preoperative hormone deficiencies occurs in about 30 to 40% of patients.

Postoperatively new endocrine deficiencies may occur in 5 to 15% of patients.

Diabetes insipidus occurs in approximately 18 to 30% of patients, but resolves in 90% of people within several weeks.

CSF fluid leak, hemorrhage, and meningitis each occur in up to one percent of patients.

Surgical correction by resection may alleviate compression of vital structures in reverse pituitary hormone secretion compromise.

Median biochemical remission rate after transphenoidal surgery is approximately 80%.

Complications of the surgery include hypopituitarism, diabetes insipidus, and CSF leaks.

Patients with prolactinoma, who are unable to take medical therapy, or do not respond to medical therapy, are candidates for transsphenoidal surgical therapy.

TSS is associated with normalization of prolactin levels in 69% of patients with the subsequent recurrence in 18% after transphenoidal surgery.

With surgery approximately 10% of patients have a recurrence over 10 years which may reflect incomplete resection, inaccessible tumor tissue, or dural nesting of hormone secreting tumor cells.

Likelihood of remission after resection includes the surgeons experience, relatively low levels of secreted hormone, and small tumors.

Preoperative tumor invasiveness determines the risk of postoperative persistent or recurrent tumor requiring adjuvant irradiation and reoperation.

Radiosurgery has a high rate of tumor control, but pituitary failure develops in about 20% of patients.

Studies have found 36% of patients have a recurrence after surgery alone, whereas 13% have a recurrence after surgery and adjuvant radio therapy.

Radiation therapy: conventional external beam, proton beam who stereotactic radiosurgery, is generally reserved for tumors resistant to medical treatment or not controlled by surgery.

Tumor growth is usually arrested over a period of several years, and adenoma derived hormone hypersecretion may persist during initial years after radiation.

In most patients pituitary failure develops within 10 years after radiation therapy, and lifelong hormone replacement is required.

Mortality from cerebrovascular causes increase by a factor of four after pituitary radiation.

Postoperative transphenoidal surgery complication rates, such as anterior hypopituitaryism, diabetes insipidus, and CSF leak occur in less than 20% of patients.

Central adrenal, insufficiency develops, postoperatively it all patients who are in remission in frequently process from within one year requiring supraphysiological glucocorticoid doses, followed by slow tapering to avoidglucocorticoid withdrawal syndrome, and secondary adrenal insufficiency.

Radiation therapy is administered by delivering photons or protons to the pituitary tumor.

Radiation can be delivered in a single fraction for smaller tumors that are far from the optic chasm.

Radiation therapy is second or third line therapy in patients with pituitary adenomas that occur after surgery.

Radiation therapy may be used after surgery and medical therapy for patients with somatotropinomas, prolactinomas, or thyrotropinomas.

In patients with Cushing disease, radiation therapy may be administered to those receiving medical therapy for biochemical control.

Radiation therapy stops tumor growth in more than 95% of patients with clinically functioning adenomas.

Recurrence of pituitary adenoma occurs in 5 to 15% of patients after surgical removal and is more common with prolactinoma.

In patients treated for acromegaly all cause mortality is not increased above the general population in patients who achieve a normal serum IGF –1 level.

Patients with Cushing’s disease in long-term remission have elevated risks of stroke, venous thromboembolism, sepsis and increased all cause mortality when compare with the general population, as well as increased cardiovascular mortality.