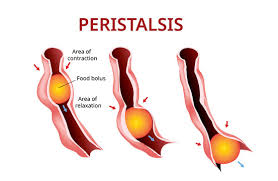

Peristalsis is a type of intestinal motility, characterized by radially symmetrical contraction and relaxation of muscles that propagate in a wave down a tube, in an anterograde direction.

Peristalsis is a type of intestinal motility, characterized by radially symmetrical contraction and relaxation of muscles that propagate in a wave down a tube, in an anterograde direction.

It is progressive coordinated contraction of involuntary circular muscles, which is preceded by a simultaneous contraction of the longitudinal muscle and relaxation of the circular muscle in the lining of the gut.

In the human gastrointestinal tract, smooth muscle tissue contracts in sequence to produce a peristaltic wave, which propels a ball of food along the tract.

The peristaltic movement comprises relaxation of circular smooth muscles, then their contraction behind the chewed material to keep it from moving backward, then longitudinal contraction to push it forward.

Peristalsis is generally directed towards the anus by a sense of direction that might be attributable to the polarization of the myenteric plexus.

The food bolus stretches the gut smooth muscle that causes serotonin to be secreted to sensory neurons, which then get activated.

These sensory neurons, in turn, activate neurons of the myenteric plexus, which then proceed to split into two cholinergic pathways: a retrograde and an anterograde.

Activated neurons of the retrograde pathway release substance P and acetylcholine to contract the smooth muscle behind the bolus.

The activated neurons of the anterograde pathway release nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide to relax the smooth muscle caudal to the bolus.

This allows the food bolus to effectively be pushed forward along the digestive tract.

Esophagus

After food is chewed into a bolus, it is swallowed and moves through the esophagus.

There are smooth muscles that contract behind the bolus to prevent it from being squeezed back into the mouth.

Rhythmic, unidirectional waves of contractions work to force the food into the stomach.

The migrating motor complex (MMC) helps trigger peristaltic waves, working in one direction only.

The migrating motor complex sole esophageal function is to move food from the mouth into the stomach.

A primary peristaltic wave occurs when the bolus enters the esophagus during swallowing, forcing the bolus down the esophagus and into the stomach in a wave lasting about 8–9 seconds.

If the food bolus gets stuck or moves slower than the primary peristaltic wave when it is poorly lubricated, then stretch receptors in the esophageal lining are stimulated and a local reflex response causes a secondary peristaltic wave around the bolus, forcing it further down the esophagus, and these secondary waves continue indefinitely until the bolus enters the stomach.

Peristalsis is controlled by the medulla oblongata.

Esophageal peristalsis can be evaluated by performing an esophageal motility study.

Tertiary peristalsis, is dysfunctional and involves irregular, diffuse, simultaneous contractions seen in esophageal dysmotility disorders and on a barium swallow appears as a “corkscrew esophagus”.

During vomiting, the propulsion of food up the esophagus and out the mouth comes from the contraction of the abdominal muscles, as the esophagus does not reverse peristalsis.

When a peristaltic wave reaches at the end of the esophagus, the gastroesophageal sphincter opens, allowing the passage of bolus into the stomach.

The gastroesophageal sphincter normally remains closed and does not allow the stomach’s food contents to move back.

The churning movements of the stomach’s muscular wall blend the food thoroughly with the acidic gastric juice, producing a mixture called the chyme.

The pyloric sphincter keeps on opening and closing so the chyme is fed into the intestine in installments.

The semifluid chyme is processed and is passed through the pyloric sphincter into the small intestine.

Once past the stomach, a typical peristaltic wave lasts only a few seconds, traveling at only a few centimeters per second.

Its primary purpose is to mix the chyme in the small intestine rather than to move it forward in the intestine.

The process of mixing and continued digestion and absorption of nutrients occurs as the chyme gradually works its way through the small intestine to the large intestine.

In contrast to peristalsis, the segmentation contractions result in churning and mixing without pushing materials further down the digestive tract.

The large intestine’s peristalsis of the type that the small intestine uses, it is not its primary propulsion.

The large intestine’s general contractions are mass action contractions that occur one to three times per day in the large intestine, propelling the chyme (feces) toward the rectum.

Mass movements often tend to be triggered by meals, as the presence of chyme in the stomach and duodenum prompts them via the gastrocolic reflex.

Minimum peristalsis is found in the rectum part of the large intestine as a result of the thinnest muscularis layer.

The human lymphatic system has no central pump, so it circulates through peristalsis in the lymph capillaries as well as valves in the capillaries, compression during contraction of adjacent skeletal muscle, and arterial pulsation.

During ejaculation, the smooth muscle in the walls of the vas deferens contracts reflexively in peristalsis, propelling sperm from the testicles to the urethra.

Ileus is a disruption of the normal propulsive ability of the gastrointestinal tract caused by the failure of peristalsis.