Aggressive tumor with early and intermediate stage disease uncommon.

Aggressive tumor with early and intermediate stage disease uncommon.

Hypopharyngeal carcinoma is an uncommon head and neck cancer.

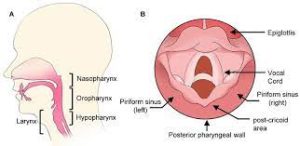

As part of the pharynx, the hypopharynx is located behind the entire length of the larynx.

The hypopharynx extends from the plane of the epiglottis to the lower border of the cricoid cartilage.

Moreover, the pharynx is further classified into three regions: (1) the piriform sinuses, (2) the posterior pharyngeal wall, and (3) the post-cricoid area.

Hypopharyngeal carcinoma is relatively rare in all head and neck cancers, making up approximately 3–5% of cases.

The overall worldwide incidence rates occur at a rate of 0.8 per 100,000 (1.4 in men and 0.3 in women).

Bangladesh had the highest incidence with 4.8 per 100,000.

The incidence has declined in America, in part due to decreasing intake of tobacco.

Tobacco consumption occurs in > 90% of patients and alcohol abuse in > 70% of patients, are the two well-established risk factors for hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

Adenocarcinoma is less frequent in hypopharyngeal malignancies, accounted for around 5% of cases.

Compared to non-smokers, it increased the risk by 9.5-fold for the long-term smoker.

Alcohol drinkers increased the risk up to 125.2-fold for alcoholics (> 100 g/day).

There is a synergistic carcinogenic effect between tobacco use and alcohol abuse.

It is five times more common in males than in females and mainly occurs in the aged 50 to 70 years.

It rarely occurs at young ages.

Tobacco consumption and alcohol abuse contribute to the tumorigenesis.

Hypopharyngeal cancer’s other risk factors include: nutritional factors. Plummer-Vinson syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and chronic infectious diseases.

Most hypopharyngeal cancers are squamous cell carcinomas, accounting for up to 95% of cases.

Most lesions are poorly differentiated.

Hypopharyngeal cancer occurs most in the piriform sinuses in 60–85% of patients, followed by the posterior pharyngeal wall up to 10–20% and rarely in the post-cricoid area in 5–15% of patients.

Tumors of the pyriform sinus and the posterior pharyngeal wall occur mainly in males, while post-cricoid carcinoma is more often occurs in females.

Hypopharyngeal cancers remain asymptomatic for an extended period.

Common symptoms of hypopharyngeal carcinoma are globus pharyngeus, sore throat, dysphagia, otalgia, neck mass, hoarseness, and dyspnea.

A neck mass is the typical clinical manifestation of hypopharyngeal carcinoma, due to the rich lymphatic network and vascular anatomy in the neck, allowing metastases to the cervical nodes.

More than half of patients with hypopharyngeal carcinoma have enlarged cervical nodes at initial presentation.

The neck metastases rate is higher (> 75% of patients) in pyriform sinus cancers, as compared with the neck metastases rate in the posterior pharyngeal wall and post-cricoid cancers.

Lymphatics from pyriform sinuses usually result in levels II-III and retropharyngeal node metastasis.

And the posterior pharyngeal wall lymphatic metastasis area is more occurred to level II lymph node metastasis.

Lymph node metastasis of the post-cricoid region prefers to go to levels IV-VI nodal metastasis. Sticking or irritative sensation in the throat could be an early symptom.

Sore throat, dysphagia, and referred otalgia on swallowing may be present.

Approximately 75–80% of patients with hypopharyngeal cancer are initially diagnosed with advanced-stage disease.

Early and intermediate disease controlled with radiation and chemotherapy.

In early-stage patients, primary surgical resection and radiotherapy achieved similar survival and locoregional control rates.

T1–T2 malignancies with N0–N1 can usually be treated with radiation alone, open surgery, or transoral surgery.

After primary surgery adjuvant radiotherapy is often required.

Advanced disease managed by laryngopharyngectomy.

There is no difference in overall survival or cause specific survival after surgery with or without adjuvant radiation therapy compared to definitive radiation therapy for patients treated for squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx (Hall SF).

Patients treated with definitive RT for hypopharyngeal cancers are more likely to have swallowing probleems than those irradiated for cancers of the oropharynx and larynx (Mendenhall WM).

Patients with hypopharyngeal cancer have an exceptionally high risk of a synchronous or metachronous second primary cancer.

In head and neck cancers, the overall incidence of the synchronous second primary cancer is estimated to be 12%.

Hypopharyngeal cancer has a high incidence of second primary cancer: esophagus (27%) and lung (6.34%)

Patients with hypopharyngeal carcinoma should undergo regular surveillance endoscopy and chest CT scan to detect a second malignancy.

Most second primary cancers following a hypopharyngeal cancer diagnosis occurs within one year.

Imaging techniques can measure the tumor extent, lymph nodal involvement and staging, potential laryngeal impingement, and cartilage involvement.

A CT enhanced scan of the laryngopharynx and neck is exceptionally worthy in evaluating laryngeal cartilage invasion.

MRI is better to evaluate soft-tissue extension.

They are complementary examinations of each other and reveal the tumor invasive range.

Approximately 6% of patients with hypopharyngeal cancer have distant metastases , making a chest CT scan or PET/CT a recommendation.

Cancer of the hypopharynx has an abysmal prognosis of all head and neck cancers.

75–80% of patients have advanced-stage disease (stage III/IV) when initially diagnosed.

About 60–75% of patients have cervical lymph node metastasis (N1–3).

About 50% of the untreated cancer patients survive four months after the initial diagnosis, and less than 20% of patients surviving more than one year [49, 50].

The general treatment principle is to improve the postoperative life for patients on the premise of ensuring that the tumor is removed completely.

Treatment selection requires optimizing swallowing and speaking functions and to prevent a long-term aspiration and tracheostomy dependence and acquire a balance between disease cure and anatomical preservation of tissue.

For early-stage tumor (T1/T2 with N0/N1) primary radiotherapy or open surgical procedures: results of the retrospective analysis showed the similarity between the long-term survival prognosis.

Postradiation local control rate is achieved in 68–90% of patients with T1 tumors and approximately 75% cases in T2 lesions.

The goal of radiation with concurrent chemotherapy is to acquire speaking and swallowing functional of invaded area and laryngeal preservation rates for five years above 70%.

Radiation-related injuries to the neck tissues include substantial acute and late toxicity: radiation-related dermatitis usually alleviated within 6–12 weeks of treatment, permanent xerostomia, aspiration and chronic dysphagia may occur.

Surgery is also an available approach for early-stage lesions compared with radiotherapy.

Postoperative T1T2 diseases with high-risk factors: positive margins, positive lymph nodes, extracapsular tumor extension and locally advanced tumors should receive radiotherapy.

For T1/T2 tumor, minimally invasive surgery with reducing morbidity has become a surgical option.

A variety of transoral surgical techniques/instrumentation, such as laser, plasma, oral robot surgery, are options, with preserving laryngeal function.

Transoral surgery presents fewer complications than open surgery with decreased nasogastric tube dependence down from 30% to 3% within 1 year, and Increases the laryngeal conservation rate by over 70%.

Local control and cancer-free survival rates via radiotherapy and open surgery in T1/T2 diseases have been achieved through transoral routes, especially in early-stage lesions.

Transoral robotic surgery has been considered a valid treatment for early hypopharyngeal carcinoma, and is also regarded as more appropriate for early cases without adjuvant treatment.

For the need of larynx-preservation, non-surgical treatments are considered: combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

For stage IV malignancy, chemotherapy or concomitant therapy heightens therapeutic efficacy, which is better in locoregional control and survival rates than radiation alone.

In a randomized trial including 202 cases indicated that induction chemotherapy +radiotherapy achieved almost same disease survival as immediate surgery.

Guidelines recommend total laryngectomy for T3/T4patients with heavy tumor load and poor laryngeal function before induction chemotherapy.

Surgery remains the preferred treatment for advanced-stage hypopharyngeal cancers.

Partial pharyngectomy with a partial laryngectomy, is utilized in a series of hypopharyngeal cancers for hypopharyngeal cancers with small to medium lesions.

Reconstruction surgery reduces the incidence of postoperative complications such as pharyngeal fistula, fatal bleeding, or infection, and improves functions of speaking, swallowing, and breathing.

The methods of reconstruction include regional flaps or more vascularized free tissue transfer.

Almost all patients with hypopharyngeal carcinoma have a high incidence of lymph node metastasis in the neck.

Pyriform fossa cancer has the highest cervical metastasis rate of (> 75%).

The lymph node metastasis rate of the posterior pharyngeal wall and posterior ring carcinoma is between 30% and 60%.

Bilateral neck dissection should be considered with the tumor across the midline and tumors located in the posterior pharyngeal wall, medial Pyriform wall, or posterior annular region.

Paratracheal positive nodes (level VI) are frequently involved by tumors located in the pyriform apex or post-cricoid area, and is associated with

a much worse prognosis.

Paratracheal node dissection should be strongly involved in this area, both for the thoroughness of removing all tumor and strict disease staging.

The retropharyngeal nodal disease is common in lateral pyriform and posterior pharyngeal, existing in 40% of advanced patients.

Retropharyngeal nodes should be taken into adjuvant radiotherapy in the setting of an unremovable surgical lesion.

In advanced stages, these positive nodes clinically/radiographically may be an indication for non-surgical treatment.

Due to the fact most hypopharyngeal tumors relapse within two years after initiate treatment, rigorous surveillance should be followed three months after treatment until two years and every six months for 3–5 years to screen early local recurrence and second primary tumors.