Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), formerly known as bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP), is an inflammation of the bronchioles and surrounding tissue in the lungs.

It is a form of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia.

It is often a result of a complication of an existing chronic inflammatory disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, or it can be a side effect of certain medications such as amiodarone.

Clinical and radiological imaging resemble infectious pneumonia.

Diagnosis is suspected after there is no response to multiple antibiotics, and blood and sputum cultures are negative for infectious diseases.

The process is unresolved pneumonia in which the alveolar exudate persists and eventually undergoes fibrosis in the alveoli., and is referred to as organizing.

Fibroblasts are recruited to the alveolar lumen, which proliferate, and differentiate into myofibroblasts and form fibroinflammatory buds characteristic of organized pneumonia.

These buds are intermixed with loose connective tissue rich in collagen fibronectin, pro collagen type III and proteoglycans.

Protein dusregulation involving the vascular endothelial growth factor, fibroblast growth factor and matrix metalloproteinases occurs correlating with the angiogenic activity of the newly formed fibromyxoid connective tissue in organizing pneumonia.

The resolution and/or remodeling that occurs following bacterial infections is commonly referred to as organizing pneumonia, both clinically and pathologically.

Eventually the integrity and function of the areolar unit are restored.

The usual presentation is the development of nonspecific systemic of fevers, chills, night sweats, fatigue, weight loss, and respiratory difficulty in breathing, and cough symptoms in association with filling of the lung alveoli that is visible on chest x-ray.

The presentation is so suggestive of an infection that the majority of patients with COP have been treated with at least one failed course of antibiotics by the time the true diagnosis is made.

The lung injury appears to occur at a single moment and without major disruption of the lung architecture.

It an inflammatory and fibroproliferative process characterized by intraalveolar proliferation that is reversible with immunosuppressive or anti-inflammatory therapy.

This reversibility is in stark contrast to other fibrotic processes, especially interstitial pneumonia, which is not reversible.

Early events include denudation of the epithelial basal lamina and necrosis of type 1 alveolar epithelial cells with gaps in the basal lamina.

This alveolar epithelium injury allows leakage of plasma proteins, fibrin inflammation, migration of inflammatory macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils and occasionally plasma cells and mast cells into the alveolar space.

It is often misdiagnosed, and is associated with a high recovery rate.

Prevalence is about 5 to 10%.

Mean diagnostic age is 50 to 60 years and is rately reported in children.

The incidence is slightly higher among men than women.

Approximately 54% of patients have never smoked and 46% are former or current smokers.

It is suggested the environmental factors have a role in its initiation.

Causes:

Pulmonary infection by bacteria, viruses and parasites

Drugs: antineoplastic drugs, erlotinib, amiodarone

Chemical exposure, most notably to diacetyl

Vaping

Ionizing radiation

Inflammatory diseases

Systemic lupus

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA-associated COP)

Scleroderma

Bronchial obstruction

Proximal bronchial squamous cell carcinoma

SARS-CoV-2

The majority of patients with COVID-19 and pulmonary involvement also have secondary organizing pneumonia (OP) or its histological variant, acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia, which are both well-known complications of viral infections.

Patients with COP do you not respond to antibiotic treatments.

Symptoms of COP are rough and subacute and emerge over a period of several weeks to several months.

Symptoms of COP are rough and subacute and emerge over a period of several weeks to several months.

Common symptoms include a dry cough in more than 70% of cases, and dyspnea in 62% of cases is mild to moderate and worsened by exertion.

An influenza like symptom pattern is reported in 10 to 15% of cases.

Fever is present in 44% of cases of COP.

Physical examination findings include inspiratory crackles and 60% of cases, clubbing in less than 3% of cases.

DIAGNOSIS: based on the combination of clinical, radiologic, and pathological expertise.

Higher risk of COP with inflammatory diseases like lupus, dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, and scleroderma.

On clinical examination, crackles are commonly auscutated.

Rarely, patients may have clubbing (<5%).

Physical examination reveals frequent presence of rales upon auscultation.

Pulmonary function tests usually show decreased capacity and hypoxia.

The reversed halo sign is seen in about 20% of individuals with COP.

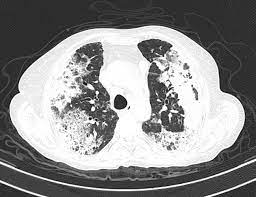

Chest x-ray has features similar to an extensive pneumonia, with both lungs showing widespread white patches.

Plain chest radiography shows normal lung volumes, with characteristic patchy unilateral or bilateral consolidation.

Small nodular opacities occur in up to 50% of patients and large nodules in 15%.

The white patches may seem to migrate from one area of the lung to another.

Radiologic abnormalities can manifest as migratory opacities with areas of spontaneous progression and new areas of consolidation.

A halo sign characterized by a rim of consolidation with more central clearing is observed in less than 5% of cases but is a relative specific finding for organizing pneumonia.

Follow up CT find consolidation associated with partial or complete resolution of the parenchymal abnormalities.

Laboratory testing is nonspecific, but inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C reactive protein level, and leukocyte count are frequently elevated.

Patients with organizing pneumonia may present weeks to months before the development of an associated connective tissue disorder and testing for such diseases with ANA, rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, creatinine kinase, anti-Opoisomerase (anti-Scl-70) antibody, anti-centromere antibody , anti-double stranded DNA and anti—Jo-1 and other antisynthetase antibodies is appropriate when connective tissue disorder is suspected.

Computed tomography (CT) helps to confirm the diagnosis: high resolution computed tomography, airspace consolidation with air bronchograms is present in more than 90% of patients, often with a lower zone predominance.

A subpleural or peribronchiolar distribution is noted in up to 50% of patients.

Ground glass appearance or hazy opacities associated with the consolidation are detected in most patients.

There is a reduced diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO).

Airflow limitation is uncommon.

Gas exchange is usually abnormal and mild hypoxemia is common. Broncoaveolar lavage analysis is recommended Of COP is suspected.

Bronchoalveolar lavage reveals up to 40% lymphocytes, along with more subtle increases in neutrophils and eosinophils.

In patients with typical clinical and radiographic features, a transbronchial biopsy that shows the pathologic pattern of organizing pneumonia and lacks features of an alternative diagnosis is allows diagnosis and ability to start therapy: the histopathologic pattern is organizing pneumonia with preserved lung architecture, which is not exclusive to COP and must be interpreted in the clinical context.

Pulmonary function tests can show restrict restricted ventilatory defect and reduced diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide.

Lower volumes are normal end up to 25% of patients, and they are flow obstruction is not a feature except for patients who have been smokers.

The lungs are stiff and noncompliant and can return to normal in patients who respond to treatment.

Arterial hypoxemia is common.

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia is characterized by the presence of plugs of loose organizing connective tissue within alveolar ducts, alveoli, and bronchioles, known as Masson bodies.

Unusual presentations of organizing pneumonia is that of patchy bilateral disease.

There are unusual variants of organizing pneumonia where it may appear as multiple nodules or masses, that may be indistinguishable from lung cancer based on imaging alone.

Most patients recover from COP with corticosteroid therapy.

chest x-ray findings are distinctive with bilateral opacities that are patchy or diffuse and consolidative or hazy in the presence of normal lung volumes.

CT scans with more resolution reveal more extensive disease than seen on plain chest x-ray, with peripheral and multifocal consolidation.

Lesions of COP are found in all lung zones with a slight predominance of subpleural and lower lung distribution.

X-ray findings include groundglass opacities, nodules up to 8 millimeters in diameter.

COP can often be managed without histopathological confirmation.

Histopathologic examination teveals intraluminal plugs of loose connective tissue that involve alveolar spaces and alveolar ducts and they also involve bronchioles.

Focal organizing pneumonia is relatively rare with less than 15% of patients with COP.

These patients are often asymptomatic and surgical resection of the solitary lesion is curative.

A subset of patients with COP can present with a rapidly progressive clinical course that may be associated with respiratory failure and death.

The differential diagnosis includes a broad-spectrum of diseases with similar clinical and radiological features.

The most important process in the differential diagnosis is community acquired pneumonia.

Other entities that should be considered are: hypersensitivity pneumonitis, eosinophilic pneumonia, alveolar hemorrhage, vasculitis, adenocarcinoma of the lung, pulmonary lymphoma, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia.

Treatment:

treatment is empirical and management is initiated depending on the severity of the clinical, physiological and radiological abnormalities and the rapidity of the disease progression.

10% of patients report spontaneous improvement, particularly those with mild disease.

Glucocorticoid therapy is the preferred treatment for symptomatic patients with respiratory impairment due to COP..

Glucocorticoid therapy usually results in clinical improvement and resolution of radiologic findings within three months after diagnosis.

Relapses or common following reduction or discontinuance of the treatment.

Studies have suggested that macrolide antibiotics with anti-inflammatory properties such as erythromycin or clarithromycin may be useful adjuncts or alternative to oral glucocorticoid therapy.

Mycophenolate mofetil inhibits proliferation of lymphocytes and has been used as a glucocorticoid sparing agent, as has cyclosporine rituximab and intravenous immune globulin.

The prognosis is generally good for patients with COP.

Rarely patients have progressive respiratory failure and can result in death, but that occurs in less than 10% of cases.

Five-year survival rates exceed 90%.