Cholestasis refers to the impairment in bile formation or flow which can manifest clinically with fatigue, pruritus, and jaundice.

Cholestasis refers to the impairment in bile formation or flow which can manifest clinically with fatigue, pruritus, and jaundice.

The differential diagnosis of cholestatic liver diseases is broad.

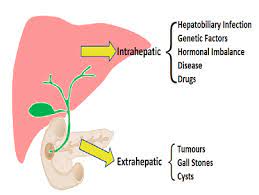

Cholestasis etiologies vary by the anatomical location of the defect and its acuity of presentation.

Causes of Acute and Chronic Cholestasis:

Biliary obstruction- cholelithiasis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Cholangitis

Secondary sclerosing cholangitis

Drug-induced liver injury

Primary biliary cholangitis

Sepsis

Drug-induced liver injury

TPN-associated cholestasis TPN-associated cholestasis

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

Congestive hepatopathy

Alcoholic hepatitis

Biliary atresia

Infiltrative disorders

• Sarcoidosis

• Mastocytosis

• Lymphoma

• Fungal infections

• Tuberculosis

Genetic disorders

• Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis

• Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis

• Alagille syndrome

• Cystic fibrosis

TPN = total parenteral nutrition.

Bbiochemical evidence of cholestasis includes increases in serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase (GGT), followed by onset of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.

If cholestasis persists for longer than 3 to 6 months it is considered to be chronic.

Notably, some causes of acute cholestasis, such as

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN)-associated cholestasis or drug-induced liver injury (DILI), have the potential for the development of chronic cholestasis.

Cholestatic disorders are defined as intra- or extrahepatic.

Intrahepatic cholestasis is caused by defects in bile canaliculi, hepatocellular function, or intrahepatic bile ducts.

Extrahepatic cholestasis affect the extrahepatic ducts, common hepatic duct, or common bile duct.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis, can affect both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts.

Patients with cholestasis may develop jaundice, acholic or clay-colored stools, darkening of the urine, and pruritus.

Patients with extrahepatic cholestasis may have symptoms of biliary colic or have a palpable gall bladder.

Jaundice accompanied by fever and abdominal pain is characteristic of cholangitis.

Chronic cholestasis increases risk for several complications: impairs the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins and therefore predisposes to metabolic bone disease; Primary biliary cholangitis is associated with hyperlipidemia and cutaneous lipid deposits, which manifest as xanthomas and xanthelasmas; progression to cirrhosis with portal hypertension, ascites, spider angiomata, and gynecomastia.

Choledocholithiasis, the presence of gallstones within the common bile duct

is among the most common causes of acute cholestasis.

Most cases of choledocholithiasis occur secondary to migration of gallstones from the gallbladder into the CBD and are composed largely of cholesterol stones.

Primary common bile duct stones are less common.

Primary common bile duct stones

are usually brown-pigmented stones composed of calcium bilirubinate.

Risk factors for primary choledocholithiasis are bile stasis, papillary stenosis, dilation of the CBD, periampullary diverticulum, and recurrent or persistent infection of the biliary system.

Choledocholithiasis may be asymptomatic, but most present with right upper-quadrant or epigastric pain, jaundice, fever, nausea, or vomiting. Importantly, early biochemical features of biliary obstruction are not cholestatic.

Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI) accounts for approximately 52% of cases of fulminant hepatic failure in the United States.

Drug-Induced Liver Injury can be categorized into hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed cholestatic and hepatocellular injury.

The category of DILI is defined according to the R ratio.

(ALT)/upper limit of normal for ALT; patient’s ALP/upper limit of normal for ALP.

An R ratio of greater than 5 defines hepatocellular DILI, whereas cholestatic DILI is characterized by an R ratio of less than 2.

DILI is characterized as mixed if the R ratio is between 2 and 5.

Cholestatic injury accounts for approximately 30% of cases of DILI.

Antimicrobial agents followed by

supplements are the most common causes of nonacetaminophen-induced DILI.

Herbal products are most often responsible for DILI in Asian countries.

Medications associated with cholestatic DILI include, antibiotics (amoxicillin-clavulanate, macrolides, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole), antifungals, anabolic steroids, antineoplastic agents, oral contraceptives, and psychotropic drugs such as chlorpromazine.

Management of DILI relies on discontinuation of the offending medication.

The majority of patients with DILI will experience complete recovery.

Jaundice may take months to resolve after cholestatic DILI.

In acute liver failure due to nonacetaminophen drug-induced liver injury, N-acetylcysteine administration may improve transplant-free survival.

Cholestatic injury has a better prognosis than hepatocellular DILI, but it is more likely to persist and lead to chronic injury (31% vs 13%).

Cholestasis is a common with sepsis and may occur in up to 40% of critically ill patients.

Jaundice with critical illness is often multifactorial: hemolysis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, heart failure, renal insufficiency, and drug toxicity.

The degree of jaundice is correlated with increased mortality in critically ill patients.

Sepsis Induced impaired bile flow in the is the primary driver of cholestasis.

Inflammatory mediators, including lipopolysaccharide, impair the gene expression and activity of proteins.

These proteins transport bile salts into hepatocytes and subsequently excrete them into bile canaliculi.

Endotoxins impair clearance of both conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin.

Hemolysis during sepsis may propagate cholestasis by overwhelming the liver’s ability to uptake and secrete bilirubin.

Sepsis-induced cholestasis is associated with bilirubin levels typically range from 2 to 10 mg/dL.

Serum alkaline phosphatase rarely exceeds 2 to 3 times the upper limit of normal and is accompanied by modest elevations in serum aminotransferases.

Differential diagnosis for cholestasis secondary to sepsis includes: biliary obstruction and drug induced liver injury.

Treatment of cholestasis secondary to sepsis is appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is characterized by pruritus, elevated serum aminotransferase levels, and increased total serum bile acids, which presents in the late second or third trimester of pregnancy.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy usually resolve following delivery, but may recur with subsequent pregnancies.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

incidence has significant geographic variation: from <1% in Australia, Canada, and parts of Europe, to 27.6% in parts of Chile.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

likely reflects a combination of genetic, environmental, and hormonal factors.

Women with underlying chronic liver disease, such as hepatitis C and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, may be at increased risk for intrahepatic cholestasis.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

manifests with pruritus of the palms and soles, which may progress to a generalized process.

With Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy abdominal discomfort, jaundice, and steatorrhea can occasionally develop.

The elevation in the serum bile acids constitutes the most sensitive and specific diagnostic indicator for Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy .

In Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy maternal bile acids cross the placenta, and accumulate in the fetus and amniotic fluid.

The impaired normal transplacental gradient of bile acids increases risk of preterm delivery, stillbirth, meconium staining of amniotic fluid, and neonatal respiratory distress syndrome.

Neonatal risks correlates with increasing maternal serum bile acid levels, particularly when they exceed 40 micromol/L.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

does not appear to have long-term impact on maternal morbidity and mortality.

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) 10 to 15 mg/kg per day is the primary treatment for Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

Ursodeoxycholic acid improves pruritus and liver biochemistries, but no improvement in perinatal outcomes.

Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN)

can promote liver abnormalities including: abnormal liver tests, steatosis, steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and cholestasis.

TPN causes elevation in bilirubin, usually two weeks after its initiation.

TPN-induced cholestasis, if not addressed can progress to cirrhosis and liver failure.

TPN-induced cholestasis is multifactorial; lack of enteral nutrition; toxicity of TPN components; and predisposition from the underlying condition, which imposes the need for TPN.

With TPN the absence of enteral nutrition alters the pathophysiology of the gut in ways that predispose to cholestasis.

Gut microbiome changes with TPN mechanisms: bile stasis caused by decreased release of cholecystokinin and endotoxemia from bacterial translocation and microbial alterations that affect secondary bile-acid metabolism.

TPN promotes cholestasis with high rates of glucose or lipid infusion, TPN trace elements, such as copper and manganese, can also directly cause cholestasis.

Diagnosis of TPN-induced cholestasis requires exclusion of alternative etiologies of cholestasis, maximization of enteral nutrition if possible. In patients who continue to require parenteral nutrition.

By adjusting TPN formulations or administering cyclical dosing it may improve cholestasis.

Substitution of soybean- oil–based lipid emulsions with fish-oil–based lipids has shown benefit in children and infants with liver disease secondary to parenteral nutrition.

((Primary sclerosing cholangitis)) is a chronic cholestatic liver disease characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts which leads to multifocal stricturing of the biliary tree.

Culminates in cirrhosis and portal hypertension in the majority of patients and is associated with an increased risk of hepatobiliary and colorectal malignancies.

Median transplant-free survival ranges from 10 to 21 years after diagnosis.

More than 70% of patients have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): typically, ulcerative colitis (UC).

Characteristic histologic changes in primary sclerosing cholangitis is that the bile duct is surrounded by concentric rings of periductal fibrosis.

The portal tract has mild primarily lymphocytic inflammation and also shows lymphocytic cholangitis.

The clinical presentation of PSC is variable, as many patients are asymptomatic and are diagnosed during evaluation of persistent cholestatic laboratory abnormalities.

Symptomatic patients may present with right upper-quadrant discomfort, pruritus, fatigue, and weight loss.

Cholangitis may be diagnosed in more advanced disease, secondary to obstruction from strictures.

Elevation of serum ALP is the most common laboratory abnormality in patients with PSC, although approximately 40% to 50% of patients with Primary sclerosing cholangitis may normalize their ALPs at some point in the course of their disease.

With Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)serum aminotransferases may be elevated to 2 to 3 times the upper limit of normal.

Serum autoantibodies are nonspecific and are not routinely used to establish a diagnosis of Primary sclerosing cholangitis .

MRCP is a noninvasive and an accurate and cost-effective method of detecting PSC.

With small-duct PSC have normal cholangiograms and require liver biopsies to establish the diagnosis of PSC.

There is a wide range of symptoms PSC, ranging from asymptomatic individuals to patients presenting with advanced associated malignancies or hepatic decompensation secondary to portal hypertension.

Patients with PSC are at increased risk of malignancies, including cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), gallbladder adenocarcinoma (GBCA), and colorectal cancer.

Cholangiocarcinoma is the most common hepatobiliary malignancy diagnosed in patients with PSC and is the leading cause of mortality.

Cholangiocarcinoma has a cumulative lifetime risk of 10% to 15% in PSC.

Sceening for cholangiocarcinoma annually with MRCP and CA-19-9 assessment as well as periodic monitoring for changes in liver tests or symptoms should be done in patients with PSC.

The frequency of gallbladder cancer and and hepatoma in PSC is much less common, occurring in approximately 14% and 2%, respectively.

The risk of colorectal cancer is increased among those with PSC and IBD involving the colon.

Thevrisk of colorectal cancer is 4 times higher among those with PSC-UC compared with UC alone.

Individuals with PSC-IBD should undergo annual colonoscopies with surveillance biopsies.

There is no effective medical therapy for PSC

Liver transplantation is the only effective cure for PSC.

However, PSC may still recur following liver transplantation in approximately 8.6% to 27% of persons, with a median onset of 4.7 years.

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is an autoimmune cholestatic liver disease.

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is the most common chronic cholestatic liver disease in the United States.

Most patients with PBC do not have cirrhosis.

PBC is due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors that trigger a T-lymphocyte–mediated destruction of intrahepatic bile ducts.

90% of PBC patients are women.

Typical diagnosis occurs between the ages of 40 and 60 years of age.

Concomitant autoimmune diseases are common in patients with PBC: Sjögren syndrome, thyroid disease, limited cutaneous scleroderma, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Approximately 60% of patients with PBC are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis.

Diagnosis of PBC is made on the basis of abnormal liver biochemical tests.

Common presenting symptoms in symptomatic patients with PBC are

fatigue and pruritus.

Findings on physical examination in PBC include: hepatomegaly, skin hyperpigmentation, jaundice, xanthomas, or stigmata of cirrhosis and portal hypertension in more advanced stages.

Laboratory abnormalities include elevation in ALP with normal or mild elevations in serum aminotransferases.

Elevation of serum bilirubin suggests advanced disease and constitutes a poor prognostic sign.

Lipid abnormalities are common in PBC.

Mild elevations in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) with more marked elevations in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) are common in early PBC, whereas more prominent elevations in LDL and lower HDL levels are noted in later stages of the disease.

The hyperlipidemia in PBC does not appear to confer excess cardiovascular risk, due, in part, to the fact that elevated levels of lipoprotein X (LP-X) that comprise a substantial proportion of cholesterol in patients with advanced PBC confers atheroprotection by inhibiting oxidation of LDL.

PBC can also be associated with metabolic bone disease, steatorrhea, and deficiencies of fat-soluble vitamins.

Anti mitochondrial antibody (AMA) is a disease-specific antibody for PBC, present in 95% of patients with the condition.

Hence, positive AMA in the context of cholestatic liver test elevations is sufficient to establish a diagnosis of PBC.

A liver biopsy may be required to establish a diagnosis of PBC when the AMA is negative or when there is concern for overlap syndrome with autoimmune hepatitis.

Due to the widespread use of uroxycholic acid and detection of disease at an earlier stage survival data has improved.

2 medications are approved for management of PBC in the United States: uroxycholic acid (UCDA) and obeticholic acid.

Several studies have demonstrated that UDCA at doses of 13 to 15 mg/kg per day promotes biochemical improvement, delays histologic progression, and improves transplant-free survival in PBC.

UDCA is considered first-line therapy for PBC.

Patients who have biochemical response to UDCA therapy may have similar survival to healthy controls.

Obeticholic acid (OCA) is a farsenoid X receptor agonist that modulates bile acid synthesis and secretion.

Obeticholic acid is approved for use at doses of 5 to 10 mg daily in combination with UDCA in patients with PBC who have an inadequate response to UDCA or as monotherapy in those intolerant of UDCA.

Fibrates improve liver functions in patients with PBC who are treatment-naïve or who lack complete response to UDCA.

The addition of fenofibrate in patients with incomplete response to UDCA is associated with improved transplant-free and decompensation-free survival.

Pruritus in PBC.

Antihistamines are largely ineffective.

Cholestyramine, rifampin, sertraline, and naltrexone are among agents that have shown efficacy in controlling pruritus in PBC.

Secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC) is a chronic cholestatic condition that leads to progressive hepatic fibrosis and large-duct irregular biliary stricturing and dilation.

The cholangiographic appearance of SSC is similar to PSC.

Surgical trauma caused by cholecystectomy, intraductal stones, recurrent pancreatitis, and biliary strictures as the most common obstructive causes of SSC.

Biliary stasis secondary to obstruction predisposes to recurrent cholangitis,

and formation of pigment stones and inflammatory strictures.

With biliary obstruction irreversible extensive periportal and periductular fibrosis and secondary biliary cirrhosis may develop over time.

Etiologies of Secondary Sclerosing Cholangitis:

Infection – Recurrent bacterial cholangitis,

Parasites (Cryptosporidium, Microsporidium, Ascaris, Clonorchis, Opisthorchis, Fasciola), Cytomegalovirus infection, AIDS cholangiopathy.

Toxic – Surgical exposure by instillation of formaldehyde, hypertonic saline, or alcohol into the bile ducts, or instillation of chemotherapy into the hepatic artery

Ischemic- Hepatic artery thrombosis following liver transplantation

Hepatic allograft rejection/ischemia

Radiation injury

Systemic vasculitis

Following transcatheter arterial embolization therapy

Sclerosing cholangitis in critically ill patients

Immunologic- IgG4-related disease

Eosinophilic cholangitis

Mast cell cholangiopathy

Infiltrative-Sarcoidosis

Malignancy- Langerhans histiocytosis

Miscellaneous causes of biliary obstruction-Choledocholithiasis/hepatolithiasis,

Anastomotic biliary stricture

Iatrogenic bile-duct injury

Mass/neoplasm

Portal hypertensive biliopathy

Chronic pancreatitis

Cystic fibrosis

The clinical presentation and laboratory profile in secondary sclerosing cholangitis

is very similar to that of PSC.

Recurrent bacterial cholangitis is very common in advanced stages of secondary sclerosing cholangitis.

In the event of decompensation, endoscopic or surgical intervention may be required for biliary drainage.

Biliary atresia (BA) is an idiopathic, fibro-obliterative disease of the intra- and extrahepatic biliary tree that presents in the neonatal period.

BA is a progressive disease that can rapidly culminate in biliary cirrhosis and premature death, if untreated.

Incidence of BA varies geographically: ranges from approximately 1 in 5000 live births in Taiwan to 1 in 18,000 in Europe.

BA is the most common cause of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia in infants and neonates.

BA is the leading indication for liver transplantation among children.

The etiology of BA is not known.

Its pathogenesis has been attributed to viral infection, immune dysregulation, genetic predisposition, exposure to environmental toxins, and abnormalities in morphogenesis.

The majority of patients with BA are born full-term with normal birth weights.

patients who develop BA have mild elevations in direct bilirubin before onset of symptoms at 24 to 48 hours of life.

BA patients are often asymptomatic until 2 to 6 weeks of age, at which point they develop onset of jaundice, acholic stools, and hepatomegaly.

Characteristic laboratory abnormalities include elevations in total and direct bilirubin, aminotransferases, and GGT >200 IU/L.

Diagnosis: Abdominal ultrasound may be done to exclude other causes of extrahepatic biliary obstruction such as choledochal cyst, choledocholithiasis, or sludge.

Supportive findings on histology include bile ductular proliferation, plugs of bile within bile ducts, portal tract edema, and fibrosis.

Evidence of biliary obstruction on cholangiography confirms the diagnosis, and a hepaticoportoenterostomy (Kasai procedure) should be performed shortly after the diagnosis is confirmed to restore bile flow from the liver to the proximal small intestine.

The Kasai procedures restores bile flow from the liver to the small intestine vis an anastomosis between a Roux-en-Y loop of jejunum and the hilum of the liver.

The timing of diagnosis and completion of the hepaticoportoenterostomy determines outcome in infants with BA.

Technical success is achieved among 80% of patients within the first 60 days of life, but decreases to approximately 20% when the operation is delayed at 120 days of life.

Even with successful restoration of bile flow, progressive liver disease necessitates liver transplantation in more than 80% patients with BA.

Reported 10-year survival rates after liver transplantation are 86%.

While alcoholic liver disease is not traditionally considered a cholestatic liver disease per se, but it can manifest with severe cholestasis and rapid onset of jaundice and should remain on the differential diagnosis during the evaluation of patients with intrahepatic causes of cholestasis.

Congestive hepatopathy occurs with chronic, passive congestion of the liver, which occurs secondary to heart failure and other cardiac defects.

Rare causes of cholestasis: Infiltrative disorders, such as sarcoidosis, mastocytosis, Langerhans histiocytosis, lymphoma, fungal infections, and tuberculosis.

Rarely, cholestasis can occur as a paraneoplastic phenomenon (Stauffer syndrome)without liver metastases;

in renal cell cancer but may occur in other malignancies and may be related to interleukin 6.

Genetic disorders can predispose to cholestasis: Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis.

Alagille syndrome, an autosomal dominant multisystem disorder that involves the liver and is associated with specific extrahepatic manifestations.

Approximately 70% of patients with Alagille syndrome require transplantation during childhood.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive genetic disease caused by mutations in the CF transmembrane is a multisystem disease that affects the liver in approximately 30% of patients.

The clinical manifestations of hepatobiliary CF can range from asymptomatic elevation in serum aminotransferases to cirrhosis and portal hypertension.