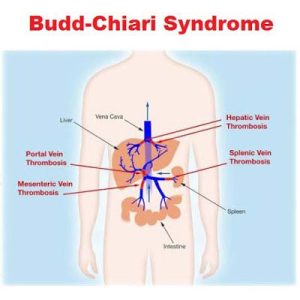

Characterized by hepatic venous outflow obstruction at the hepatic venules, large hepatic veins, inferior vena cava or the right atrium.

Characterized by hepatic venous outflow obstruction at the hepatic venules, large hepatic veins, inferior vena cava or the right atrium.

A spontaneously, fatal disease, characterized by obstruction of the hepatic venous outflow due to thrombosis or primary disease of the venous wall.

Budd–Chiari syndrome is a very rare condition, affecting one in a million adults.

The median age of diagnosis is 35 to 40 years.

The Budd-Chiari syndrome, hepatic venous thrombosis, is the least common manifestation of splanchnic venous thrombosis, with an incidence of 0.5 to 1 case per million people per year.

The primary form of the disease is extremely rare. The median age and diagnosis of primary Budd Chiari syndrome is 35 to 40 years.

An underlying disorder, such as a hereditary or an acquired hypercoagulable state is found in approximately 75% of patients and at least in 1/3 of patients have more than one prothrombotic condition is identified.

In approximately 20% of patients with BCS a prothrombotic disorder cannot be identified and the disease is classified as idiopathic.

Refers to the occlusion of the hepatic veins that drain the liver.

Clinically presents with the classical triad of abdominal pain, ascites, and liver enlargement.

A fulminant acute presentation is extremely rare.

The formation of a blood clot within the hepatic veins can lead to Budd–Chiari syndrome.

The syndrome can be fulminant, acute, chronic, or asymptomatic.

Acute ischemic liver injury, results from an abrupt venous occlusion and can cause severe liver dysfunction.

Compensatory measures include development of intrahepatic collaterals and increased arterial blood flow.

Venous collaterals may eventually become obstructed.

Subacute presentation is the most common form of Budd–Chiari syndrome.

Acute syndrome presents with rapidly progressive severe upper abdominal pain, jaundice, liver enlargement, enlargement of the spleen, fluid accumulation within the peritoneal cavity, elevated liver enzymes, and eventually encephalopathy.

The absence of clinical manifestations is not rare, but the combination of abdominal pain, fever, enlarged liver, and recent onset are highly suggestive.

The fulminant syndrome manifests early with encephalopathy and ascites.

It may lead to liver cell death and severe lactic acidosis.

Caudate liver lobe enlargement is often present.

The majority of patients have a slow onset form of Budd–Chiari syndrome, leading to venous collaterals forming around the occlusion which may be seen on imaging as a spider’s web.

Slow onset BC syndrome may progress to cirrhosis and show the signs of liver failure.

Liver abnormalities are diverse with serum anminotransferase activity, mostly increased, with rapid decrease reminiscence of an acute escaping injury.

Blood can may show hypersplenism findings related to portal hypertension.

Patiens with underlying myeloneoplasm, features of portal hypertension, including splenomegaly, contrast with platelet counts above 200,000, and high serum albumin ascites gradient increases with suspicion for BCS.

The cause of BC syndrome can be found in more than 80% of patients.

A myeloproliferative neoplasm is the most frequent underlying condition and patients should have evaluations for the JAK2, and the CAL and MPL mutations.

Other prothrombotic disorders associated with BCS include PNH, antiphospholipid syndrome, Factor Five Leiden, and Factor II mutations.

Patients should be tested for protein C, protein S, and antithrombin deficiencies.

BCS may develop during pregnancy or in the postpartum period.

The use of oral contraceptives, pregnancy, and the immediate postpartum state are <well-known prothrombotic factors that may increase the risk of BCS.

Is approximately 20% of cases the evaluation for a hypercoagulable state is negative and the disease is classified as idiopathic.

Primary Budd–Chiari syndrome occurs in 75% of cases as thrombosis of the hepatic vein.

Hepatic vein thrombosis is associated with the following:

Polycythemia vera

Pregnancy

Postpartum state

Use of oral contraceptives

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuris

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Lupus anticoagulants

Secondary Budd–Chiari syndrome occurs in 25% of cases by compression of the hepatic vein by an outside structure.

Budd–Chiari syndrome is also seen in tuberculosis, congenital venous webs and occasionally in inferior vena caval stenosis, and in patients with a tendency towards thrombosis.

Genetic tendencies include: protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, the Factor V Leiden mutation, hereditary anti-thrombin deficiency and prothrombin mutation G20210A.

Non-genetic risk factor is the use of estrogen-containing forms of hormonal contraception.

Other risk factors for BC syndrome include the antiphospholipid syndrome, aspergillosis, Behçet’s disease, dacarbazine, pregnancy, and trauma.

Many patients have a complication of polycythemia vera.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) associated with a risk for Budd–Chiari syndrome: more than other forms of thrombophilia: 12% may acquire Budd-Chiari..

With obstruction of the venous vasculature of the liver in Budd–Chiari syndrome, there is increased portal vein and hepatic sinusoid pressures as the blood flow stagnates.

Increased portal pressure causes increased filtration of vascular fluid with the formation of ascites in the abdomen.

Also collateral venous flow through alternative veins leads to esophageal, gastric and rectal varices.

With obstruction of the venous vasculature of the liver in Budd–Chiari there is centrilobular necrosis and peripheral lobule fatty change due to ischemia.

Liver congestion to due to chronic hepatic venous obstruction leads the development of hepatic fibrosis, which is triggered by hepatocyte ischemia and necrosis, along with sinusoidal thrombosis.

Increased sinusoidal pressure causes ascites formation and portal hypertension.

If this condition persists, ((nutmeg liver)’ will develop, as well as kidney failure.

Budd–Chiari syndrome is most commonly diagnosed using abdominal ultrasound and retrograde angiography, CT or MRI.

BCS is easily diagnosed by identifying obstruction of hepatic venous system on imaging studies.

Ultrasound findings in B-C may show: obliteration of hepatic veins, thrombosis or stenosis, spiderweb vessels, large collateral vessels, or a hyperechoic cord replacing a normal vein.

Abdominal Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are generally not as sensitive to make the diagnosis.

Imaging without vascular enhancement usually shows a dysmorphic liver typically would and enlarge caudate lobe.

Findings of portal hypertension with portosystemic collaterals, including esophageal, varices, splenomegaly, and ascites are common, although they may be rare.

Venovenus collaterals mostly intrahepatic are present to varying degrees.

Liver biopsy is sometimes necessary to differentiate between Budd–Chiari syndrome and other causes of hepatomegaly and ascites.

Hitopathological changes include liver cell loss due to ischemia, sinusoidal dilatation, perisinusoidal fibrosis.

Fibrosis may eventually evolve into cirrhosis.

Microscopic and macroscopic hepatocellular nodules are common.

Hepatocellular may develop overtime with the 10 year incidence of approximately 10%.

Evaluation for a JAK2 V617F mutation is recommended to diagnose a myeloproliferative syndrome.

A minority of patients can be treated symptomatically with sodium restriction, diuretics to control ascites, and anticoagulants.

Milder forms of Budd–Chiari may be treated with surgical shunts that can divert blood flow around the obstruction or the liver itself.

The TIPS procedure is similar to a surgical shunt: it accomplishes the same goal but has a lower procedure-related mortality.

If all the hepatic veins are blocked, the portal vein can be approached via the intrahepatic part of inferior vena cava, a procedure called direct intrahepatic portocaval shunt.

In patients with stenosis or vena caval obstruction angioplasty may be of benefit.

Limited studies are available for thrombolysis with direct infusion of urokinase and tissue plasminogen activator into the obstructed vein: show moderate success in treating Budd–Chiari syndrome.

Liver transplantation is an effective treatment for Budd–Chiari, but is generally reserved for patients with fulminant liver failure, failure of shunts, or progression of cirrhosis that reduces the life expectancy to one year.

Liver transplantation long-term survival ranges from 69–87%.

Up to 10% of patients may have a recurrence of Budd–Chiari syndrome after the transplant.

Approximately 2/3 of patients with Budd–Chiari are alive at 10 years.

Negative prognostic indicators include: ascites, encephalopathy, elevated Child-Pugh scores, elevated prothrombin time, and altered serum levels of sodium, creatinine, albumin, and bilirubin.

An alanineaminotransferase level that is five or more times the upper limit of normal range at presentation is associated with a poor outcome.

Survival with Budd–Chiari syndrome is dependent on underlying cause.

BCS is associated with the high mortality of greater than 80% at three years: however, when BCS is managed appropriately survival at five years exceeds 80%.

Treatment of BCS includes treatment of the underline prothrombotic disorder and restoration of hepatic venous outflow.

Management of portal, hypertension with diuretics for ascites and nonselective beta blockers as prophylaxis for variceal bleeding is recommended.

When associated with PNH should be treated with thrombolytic therapy.

All patients with BCS receive long-term anticoagulant therapy, even in the absence of a recognize prothrombotic disorder.

This type management prevents the progression of thrombosis.

In selective cases of recent thrombosis, local mechanical and chemical thrombolysis may restore venous outflow.

In cases of segmental veins stenosis affecting the inferior vena cava or hepatic vein percutaneous transluminal angioplasty with without standing, may restore hepatic venous outflow.