The cardinal symptom of spontaneous intracranial hypotension is headache that worsens on standing and subsides with lying down.

The cardinal symptom of spontaneous intracranial hypotension is headache that worsens on standing and subsides with lying down.

The interval between standing and the onset of headache is typically a minute or several minutes, but it can develop instantaneously, after a number of hours, or after a delay extends into the afternoon.

The orthostatic feature of the headache may also lessen over time.

The headache of spontaneous intra-cranial hypotension is usually holocephalic, or bilaterally suboccipital, but maybe unilateral and occasionally throbbing and can simulate migraine.

The Valsalva maneuver worsens the headache.

Additional neurologic manifestations can occur and include oral symptoms:muffled hearing sounds, pulsatile tinnitus, and hearing loss.

Symptoms across the posterior neck or stiffness, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia can use lead to diagnosis of meningitis or migraine.

Less common symptoms include facial pressure or paresthesias, and diplopia.

Rarely coma and cerebral venous thrombosis can occur days to months after the onset of spontaneous intracranial hypotension.

Coma is a result of the extreme downward displacement of the midbrain and brainstem.

Patients are suspected of having a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

The severity of the headache varies, with many mild cases undoubtedly never being diagnosed.

In some patients headaches become incapacitating.

The headache most likely the result of the decrease in CSF volume and the downward displacement of the brain, causing traction on pain-sensitive structures.

The posture-related component often becomes less prominent or even disappears over time when the underlying CSF leak is left untreated and becomes chronic.

Nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and posterior neck pain or stiffness are commonly seen and suggest meningeal irritation, mimicking subarachnoid hemorrhage or infectious meningitis.

SIH symptoms are believed to be directly related to the downward displacement of the brain due to loss of CSF buoyancy.

Diplopia, changes in hearing, and vertigo are common.

These symptoms are felt to be caused by stretching of the ocular motor, cochlear, and vestibular nerves, respectively.

Similarly, such a mechanism could explain numbness or pain at the trigeminal nerve, facial weakness or spasm in the facial nerve, and dysgeusia.

Transient visual changes, visual blurring, or visual field defects attributed to the stretching of the optic apparatus over the pituitary fossa.

In addition, stretching of cervical nerve roots could be implicated as a cause of the radicular arm pain or arm numbness occasionally found in patients with spontaneous intracranial hypotension.

Possibly, the disturbances in hearing or balance is due to change in CSF pressure is directly transmitted to that in the cochlea or labyrinth.

Rarely, severe sagging of the brain may result in coma from diencephalic or hind brain herniation, parkinsonism and dementia.

More subtle cognitive deficits are underrecognized and may not be appreciated until cognition improves following successful treatment of the spinal CSF leak.

Lumbar Puncture findings:

opening pressure at the time of lumbar puncture of less than 60 mm of water with normal, 65-195 mm of water.

Occasionally with SIH a dry tap is initially encountered, and CSF can only be obtained with aspiration using a syringe, with the patient in an upright position, or with a Valsalva maneuver.

Difficulties in obtaining a CSF sample May lead to a traumatic tap, contributing to the confusion with regard to a diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage.

The CSF often demonstrates elevated protein content and pleocytosis, which is primarily lymphocytic.

The CSF white blood cell count may exceed 200 white blood cells per milliliter, a finding that may be confused with infectious meningitis.

Brain MRI has now supplanted lumbar puncture as the diagnostic study of choice in the initial evaluation of patients suspected of having spontaneous intracranial hypotension.

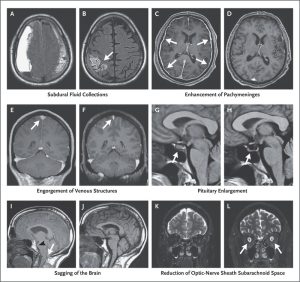

Brain MRI imaging features of intracranial hypotension are: enhancement of the pachymeninges, downward sagging displacement of the brain, and subdural fluid collections.

Subdural fluid collections are common, with most of these fluid collections being bilateral.

Subdural fluid collections are usually thin, and do not cause any appreciable mass effect.

Rarely, large symptomatic, subdural hematomas require surgical evacuation.

Brain sagging is a very specific finding of spontaneous intracranial hypotension identified by features: effacement of the suprasellar cistern, bowing of the optic chiasm over the pituitary fossa, flattening of the pons against the clivus, and downward displacement of the cerebellar tonsils.

The displacement of the cerebellar tonsils may be mistaken for a Chiari I malformation.

Pachymeningeal enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging is diffuse, only involves the pachymeninges (dura mater), and spares the leptomeninges.

Reactive hyperemia of the pituitary gland may also be seen.

Reactive hyperemia of the pituitary gland may mimic a pituitary tumor.

When CSF volume is low, it may result in compensatory enlargement of the spinal epidural venous plexus, which may become symptomatic and mimicking neoplastic, inflammatory, or degenerative disc diseases.

MRI findings may be associated with diagnostic confusion with neoplastic, inflammatory, or granulomatous disease.

Patients with spontaneous intracranial hypotension have undergone a meningeal biopsy due to the diagnostic confusion.

SIH responds to bed rest, increased intake of oral fluids, and the administration of caffeine, glucocorticoid medication, or mineralocorticoid agents.

For persistent spontaneous intracranial hypotension, the placement of lumbar epidural blood patches, using approximately 10 to 15 mL of blood is efficacious.

Computed tomographic myelography can confirm and localize the CSF leak.

Most CSF leaks are in the cervical or thoracic spine.

High-volume (20-40 mL) thoracolumbar epidural blood patch occurs with the patient being placed supine in the Trendelenburg position for 20 to 30 minutes, followed by the prone position for a similar time period, allowing blood to travel over many spinal segments toward the site of the CSF leak.

A directed epidural blood patch or percutaneous placement of fibrin glue is another consideration.

Surgical treatment is reserved for patients who have failed more conservative measures.

Computed tomographic myelography is the diagnostic test to precisely localize the CSF leak.

For most patients the diagnosis of SIH is missed initially and the diagnostic delay is significant.