Sclera

The sclera, also known as the white of the eye, is the opaque, fibrous, protective outer layer of the eye containing mainly collagen and some crucial elastic fiber.

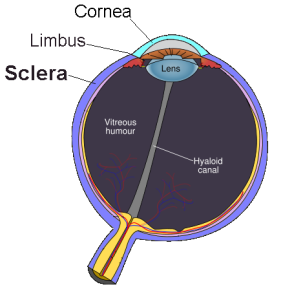

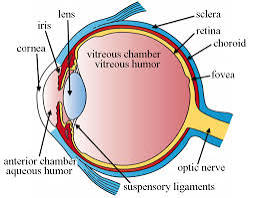

The sclera is separated from the cornea by the corneal limbus.

The sclera is derived from the neural crest.

In children, it is thinner and shows some of the underlying pigment, appearing slightly blue.

In the elderly, fatty deposits on the sclera can make it appear slightly yellow.

People with dark skin can have naturally darkened sclerae, the result of melanin pigmentation.

The whole sclera is white or pale, contrasting with the colored iris.

It forms the posterior five-sixths of the connective tissue coat of the human eyeball.

The sclera is continuous with the dura mater and the cornea.

The sclera maintains the shape of the eyeball, offering resistance to internal and external forces, and provides an attachment for the extraocular muscle insertions.

The sclera is a critical component of the eye’s anatomy, providing mechanical support, protection, and maintaining the eye’s shape and internal environment.

It is the dense, collagenous connective tissue that forms the outer protective layer of the eye.

It provides structural support and protects the internal ocular components from external injury and mechanical stress.

The sclera is composed primarily of collagen types I and III, with smaller amounts of types V and VI.

The sclera also contains proteoglycans such as decorin and biglycan, which influence its biomechanical properties.

The sclera consists of several layers: the outermost episclera, the scleral stroma proper, and the innermost lamina fusca, which transitions into the choroid.

The episclera is a thin, vascularized layer, while the stroma is the thickest part.

The stroma provides most of the sclera’s mechanical strength due to its dense collagen network.

The lamina fusca contains elastic fibers and is adjacent to the choroid.

The sclera is avascular

Its nutrients are supplied by the choroid and the vascular plexi in Tenon’s capsule and episclera.

The sclera plays a crucial role in maintaining intraocular pressure and provides a stable environment for the retina and optic nerve head, essential for clear vision.

Its viscoelastic properties allow it to withstand dynamic conditions of eye movements and variations in intraocular pressure.

The sclera is perforated by many nerves and vessels passing through the posterior scleral foramen, which is the hole that is formed by the optic nerve.

At the optic disc, the outer two-thirds of the sclera continues with the dura mater via the dural sheath of the optic nerve.

The inner third of the sclera joins with some choroidal tissue to form a plate, the lamina cribrosa, across the optic nerve with perforations through which the optic fibers pass.

The thickness of the sclera varies from 1 mm at the posterior pole to 0.3 mm just behind the insertions of the four rectus muscles.

The sclera’s blood vessels are mainly on its surface.

The vessels of the conjunctiva, which is a thin layer covering the sclera, and those in the episclera render the inflamed eye bright red.

The sclera histologically is characterized as dense connective tissue made primarily of type 1 collagen fibers.

The collagen of the sclera is continuous with the cornea.

From outer to innermost, The four layers of the sclera are: from outer to inner episclera stroma lamina fusca endothelium

The sclera is opaque due to the irregularity of the Type I collagen fibers.

This, as opposed to the near-uniform thickness and parallel arrangement of the corneal collagen.

The cornea has more mucopolysaccharide, hexosamine, to embed the fibrils.

The cornea, unlike the sclera, has six layers.

The sclera is very plainly visible whenever the eye is open, due to the white color of the human sclera, but also to the fact that the human iris is relatively small and comprises a significantly smaller portion of the exposed eye surface.

The bony area that makes up the human eye socket provides protection to the sclera.

If the sclera is ruptured by a blunt force or is penetrated by a sharp object, the recovery of full former vision is usually rare.

If pressure is applied slowly, the eye is actually very elastic.

However, most ruptures involve objects moving at some velocity.

Hemorrhage and a drop in intraocular pressure are common, along with a reduction in visual perception to only broad hand movements and the presence or absence of light.

A low-velocity injury which does not puncture and penetrate the sclera requires only superficial treatment and the removal of the object.

Small objects which become embedded and which are subsequently left untreated may eventually become surrounded by a benign cyst, causing no other damage or discomfort.

The sclera is rarely damaged by brief exposure to heat, as eyelids provide exceptional protection.

The sclera is covered in layers of moist tissue means that these tissues are able to cause much of the offending heat to become dissipated as steam before the sclera itself is damaged.

Prolonged exposure, on the order of 30 second, of temperatures above 45 °C (113 °F) will begin to cause scarring, and above 55 °C (131 °F) will cause extreme changes in the sclera and surrounding tissue.

The sclera is highly resistant to injury from brief exposure to toxic chemicals, as the reflexive production of tears at the onset of chemical exposure tends to quickly wash away such irritants, preventing further harm.

Acids with a pH below 2.5 are the source of greatest acidic burn risk, with sulfuric acid, the kind present in car batteries is among the most dangerous in this regard.

Acid burns, even severe ones, seldom result in loss of the eye.

Alkali burns, as those resulting from exposure to ammonium hydroxide or ammonium chloride or other chemicals with a pH above 11.5, will cause cellular tissue in the sclera to saponify and should be considered medical emergencies requiring immediate treatment.

Redness of the sclera is typically caused by eye irritation causing blood vessels to expand, such as in conjunctivitis.

Episcleritis is a generally benign condition of the episclera causing eye redness.

Scleritis is a serious inflammatory disease of the sclera causing redness of the sclera often progressing to purple.

Yellowing or a light green color of the sclera is a visual symptom of jaundice.

In cases of osteogenesis imperfecta, the sclera may appear to have a blue tint.

The blue tint is caused by the showing of the underlying uveal tract, choroid and retinal pigment epithelium.

With Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, the sclera may be tinted blue due to the lack of proper connective tissue.

In very rare but severe cases of kidney failure and liver failure, the sclera may turn black.