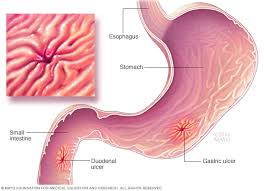

Defect or injury to mucosa of the stomach or small intestine.

Defect or injury to mucosa of the stomach or small intestine.

PUD is defined as a break in the lining of the lower esophagus, stomach, upper small intestine, but conventionally refers to only gastric and duodenum mucosal disruptions that extend into the submucosa.

Sequelae ranges from abdominal pain in G.I. bleeding to gastric outlet obstruction and perforation.

The gastric mucosal barrier protects the gastric mucosa from luminal acid and pepsin.

Gastric epithelial cells have tight junctions, resisting diffusion of luminal acid and pepsin into the mucosa.

The stomach epithelium is covered with a dense, thick adherent layer of mucus, composed of oligosaccharides/polysaccharide core, which resist proteolysis and diffusion from the stomach lumen.

Endogenous prostaglandins stimulate mucosal, blood flow, mucin production and cellular proliferation facilitating repair from injury.

Prostaglandins increase pain signals from submucosal nerves to the brain.

NSAIDs help diminish the intensity of these signals by reducing prostaglandin levels.

NSAIDs increase the risk of peptic ulcer disease by inhibiting the prostaglandin endoperoxide system (cyclooxygenase enzymes, COX).

Two primary COX enzymes exist: Cox-1 and Cox-2.

COX-1 maintains the integrity of the gastric mucosal barrier and COX-2 enzyme is induced by inflammatory cytokines.

H pylori infection increases production of gastric acid at the antrum interfering with regulatory pathways for acid secretion.

This process increases as a delivery to the duodenum increasing its susceptibility to duodenal ulcer.

Duodenal ulcers, therefore, are more likely to be caused by H pylori infection than gastric ulcers.

H pylori infection interferes with epithelial tight junctions and increases leakage of luminal contents into the sub epithelial space leading to chronic inflammation, gastric atrophy, reduced acid secretion, and gastric cancer.

In the US bleeding is the most common complication of PUD (73%), followed by perforation (9%), and obstruction (3%).

Approximately 10,000 people die of PUD in the US annually.

Prevalence estimated at 8.4%.

The most common risk factors for PUD are Helicobacter pylori infection (42%), aspirin or non-sterile anti-inflammatory drug use (36%) and idiopathic which affects approximately 22% of people.

The most common reversible factors associated with PUD are pyloric infection and NSAID use.

All patients with peptic ulcer disease should be tested for H.pylori.

Serological tests for each pylori cannot distinguish between current or previous infections.

The most widely used tests for each pylori for active infection are the stool antigen test, and urea breath test.

The estimated prevalence of peptic ulcerdisease in the US is 103 per 100,000 population and the annual incidence is 40 400,000.

Worldwide incidence and prevalence of PUD varies partly due to geographic differences in H pylori infection and patterns of NSAID use.

Higher peptic ulcer disease incidence associated with male gender, smoking, and chronic medical conditions.

Associated with increasing age.

There has been a significant decrease in peptic ulcer disease diagnoses throughout the world.

The most common cause of upper G.I. bleeding.

Due to a variety of causes including increased production of stomach acid and digestive enzyme pepsin.

Ulceration results when mucosal defense mechanisms in the upper G.I. tract or overwhelmed by endogenous factors such as acid, pepsin, or bile, or by exogenous factors.

Some stomach acid is necessary for the development of ulcers.

The two most common causes of PUD are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and Helicobacter pylori infection, both of which may present with gastric or duodenal ulcerations.

Most ulcers of the small intestine occur in the duodenum.

Two most common causes are Helicobacter pylori and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: The relative risk of developing a symptomatic ulcer is 4 for nonaspirin NSAID users and 2.9 for patients taking aspirin.

The risk for aspirin users for peptic disease was highest for people who recently started on aspirin.

The majority of PUD cases are known to be associated with age.

H. pylori creates ulceration by causing inflammation of the stomach and small intestine mucosa and also. increases stomach acid production.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs cause irritation of stomach and small intestine mucosa eroding the tissue and can dissolve the protective mucus layer that overlies the mucosa of the stomach.

The strain of H. pylori, genetic variation, exposure to NSAIDs or tobacco may influence ulcer development.

Eradicating H pylori restores, normal acid secretion, allowing ulcer healing and prevents relapse.

PPI’s are combined with antibiotics to treat ulcers caused H pylori infection.

PPI’s promote healing by reducing acidity and concentrate antibiotics in the gastric lumen by reducing acid secretion.

Increasing the gastric pH prolongs half-life of some antibiotics in increasing antibiotic exposure to the organisms.

Dual, triple and quadruple therapies exist for H pylori treatment, with PPIs added to 1,2,3 antimicrobials.

Corticosteroids, potassium chloride and bisphosphonates can cause ulcerations.

Crohn’s disease, infection with Cytomegalovirus or herpes simplex virus, can lead to gastric and small intestine.

Stress ulcers can occur in critically ill hospitalized patients as a result of decreased blood flow to the stomach and small intestine.

Gastrinomas, the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, can lead to peptic ulcers secondary to excess gastric acid.

Approximately 2/3 of patients found to have peptic ulcer disease are asymptomatic.

The most common presenting symptom is epigastric pain, which may be associated with dyspepsia, bloating, abdominal fullness, nausea, and early satiety.

In many patients there may be intermittent symptoms.

Symptoms alone do not distinguish between peptiC ulcer, reflux esophagitis, or functional dyspepsia.

Dyspepsia is the most common symptom with pain or discomfort located in the mid, upper abdomen and may radiate to the back (81%).

Duodenal ulcer pain characteristically improves with eating and worsens with fasting and at night, as the food is moved distally.

Stomach ulcer pain often increases with eating and may be accompanied by poor appetite and weight loss.

Nocturnal pain and awakening can occur due to circadian rhythm that stimulates nocturnal acid secretion.

Peptic ulcer disease can also be symptomatic and identified in patients undergoing endoscopy.

Pain is related to the acid irritation of exposed nerve endings in the ulcer crater, and inflammation in the mucosa.

Gastrointestinal bleeding, weight loss and persistent vomiting, and anemia may occur.

Diagnosis confirmed by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy or radiographic imaging.

Upper endoscopy is an urgent procedure in patients with dyspepsia and concurrent alarm systems: greater than 60 years of age, family history of upper G.I. tract malignancy, weight loss, early satiety, dysphasia, gastrointestinal bleeding, iron deficiency, or vomiting.

Endoscopy allows for establishing weather and ulcer is benign or malignant.

Physical examination is usually negative except for epigastria tenderness.

Laboratory testing may indicate the presence of anemia and iron deficiency.

A positive serum test for H. pylori may be present.

A positive test for the presence of H. pylori antigen in the stool indicates that a person is currently infected with the organism and is stronger evidence that H. pylori is the cause of an existing peptic ulcer.

The test for urea in a person’s breath is indicative of H. pylori in the stomach.

Diagnostic testing for H. pylori includes urea breath testing, stool antigen testing, rapid urease testing or histology of gastric biopsies

For patients treated for H. pylori in the past, they should undergo testing to demonstrate eradication with either stool antigen testing or urea breath testing.

Treatment: peptic ulcer disease treatment consist of acid inhibition to heal the ulcer, H pylori eradication if indicated, sensation of smoking, and appropriate management of aspirin and non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs to prevent recurrence.

For patients diagnosed with peptic ulcer while taking aspirin for prevention of cardiovascular disease its use should be discontinued, or have acid inhibitors.

Acid inhibitory drugs, reduce the damaging effects of acid and pepsin on the gastric epithelium and promote ulcer healing.

PPIs are the main medical treatment for PUD related G.I. bleeding.

PPIs promote ulcer healing by acid suppression.

PPI’s are associated with higher rates of healing than H2 receptor antagonists.

Sulcrafate and healing rates are similar to histamine receptor antagonists.

Antacids are appropriate only for temporary symptom relief.

H2 receptor antagonists are useful for patients who cannot take PPI’s due to allergies or adverse effects.

Duodenal ulcers heal more quickly than gastric ulcers because the high acidity of the stomach slows gastric ulcer healing.

Most ulcers heal in four weeks, but large gastric ulcer may require eight weeks of treatment.

For H. pylori 10 to 14 day triple therapy with bismuth and non-bismuth containing agents including clarithromycin, amoxicillin, or metronidazole.

Peptic also disease complications include: bleeding, perforation, penetration, and gastric outlet obstruction.

Risk factors associated with peptic ulcer complications include: the use of NSAIDs, aspirin, H pylori infection, smoking, acid hypersecretory state, chronic/refractory type ulcers, large size, and location of ulcers.

Cigarette smoking, psychological stress, adverse childhood living conditions, poor water quality, and genetic factors are all associated with higher risk of peptic ulcer disease.

People who currently are previously have smoked cigarettes, have the highest rates of PUD compared with never smokers.

Patients with cancer have the highest risk of death from PUD than the general population.

Complicated peptic ulcer disease risks are also related to concomitant comorbid disease, older age, poor physiological status, metabolic acidosis, acute renal failure, hypoalbuminemia, and delayed treatment.

Upper gastric or intestinal hemorrhage is the most common complication of peptic ulcer disease and is associated with morbidity and a 10% mortality.

Upper endoscopy is the best initial test in suspected peptic also bleeding as it is both diagnostic and possibly therapeutic.

Endoscopic hemostasis therapies include: injection, thermal, mechanical, or a combination of these modalities.

Endoscopic hemostasis is effective in achieving hemostasis and reducing re-bleeding, the need for blood transfusion, urgent surgery, length of hospitalization, and mortality.

Intravenous PPI should be used for 72 hours post endoscopic hemostasis followed by oral PPI therapy.

Patients who to fail endoscopic hemostasis may benefit from transcatheter angiography and treatment.

The use of surgery in the treatment of peptic ulcer bleeding has significantly diminished in the past two decades.

Perforated peptic ulcer, is a medical emergency, with associated mortality of up to 30%.

The classic clinical triad of sudden onset of abdominal pain, tachycardia, and abdominal rigidity is the hallmark of peptic ulcer perforation.

Peptic ulcer perforation is seen with abdominal distention, tenderness to palpation, guarding and rebound when peritonitis is present.

Peptic ulcer perforation is associated with leukocytosis and x-rays may show sub diaphragmatic free air is up to 15% of patients with bowel perforation.

Abdominal CT is more sensitive to detect small amounts of free air and is the imaging modality of choice in suspected perforated peptic ulcer.

Urgent surgical intervention is imperative to improve patient outcomes for perforated peptic ulcer.

Peptic ulcer penetration is the penetration of an ulcer through the bowel wall into an adjacent organ or an anatomical structure without free air, perforation or leakage of bowel continents into the peritoneal cavity.

Penetrating ulcers occur more most commonly with gastric antral ulcers and duodenal alters.

Penetration May occur into the pancreas, biliary tract, omentum, liver, vascular structures, and colon.

Complications of penetrating ulcers include abscess formation, hemorrhage, hemobilia, hyperamylasemia, and rarely, pancreatitis.

Gastric outlet obstruction is most often associated with a duodenal or pyloric channel ulcer.