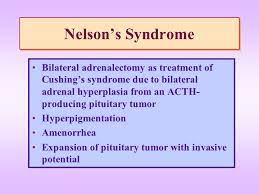

Nelson’s syndrome is a disorder that occurs in about one in four patients who have had both adrenal glands removed to treat Cushing’s disease.

Nelson’s syndrome is a disorder that occurs in about one in four patients who have had both adrenal glands removed to treat Cushing’s disease.

In patients with pre-existing adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary adenomas, the loss of adrenal feedback following bilateral adrenalectomy can trigger the rapid growth of the tumor, leading to visual symptoms of bitemporal hemianopsia and hyperpigmentation.

The severity of findings depends on the effect of ACTH release on the skin, pituitary hormone loss from mass compression, as well as invasion into surrounding structures around the pituitary gland.

With improvements in the identification and care for patients with Cushing’s disease the consideration of bilateral adrenalectomy has decreased markedly.

The common symptoms include:

hyper-pigmentation of the skin

visual disturbances

headaches

abnormally high levels of beta-MSH and ACTH

abnormal enlargements of the pituitary gland,

interruption of menstrual cycles in women

Common causes include bilateral adrenalectomy for the treatment of Cushing’s disease, and hypopituitarism.

The onset of the disease can occur an average of up to 15 years after adrenalectomy.

A preventative strategy is prophylactic radiotherapy when a bilateral adrenalectomy is being performed in order to prevent Nelson’s syndrome from manifesting.

Screening can also be done with MRI to visualize the pituitary for tumors.

Hyper-pigmentation and fasting ACTH levels within plasma above 154 pmol/L are predictive of Nelson’s syndrome after an adrenalectomy.

Risk factors for Nelson’s syndrome include being younger in age and pregnancy.

After a bilateral adrenalectomy cortisol levels are no longer normal, and CRH production is increased as it is not suppressed within the hypothalamus.

The increased CRH levels promote the growth of the pituitary tumor.

Corticotrophinomas are generated from corticotroph cells.

Diagnosis

MRIs

CAT scans

Blood studies reflect the absence or presence of aldosterone and cortisol.

Physical examinations determine vision, skin pigmentation,and the cranial nerves.

MRIs allow for adenomas to be detected.

Blood pressure, eye examination, thyroid examination, abdominal examination, neurological examination, skin examination and pubertal staging needs to be assessed.

Through blood pressure and pulse readings can indicate hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency.

Hyper-pigmentation, hyporeflexia, and loss of vision can also indicate Nelson’s syndrome when assessed together.

Common treatments for Nelson’s syndrome include radiation or surgical procedure.

Radiation allows for the limitation of the growth of the pituitary gland and the adenomas.

If the adenomas start to affect the surrounding structures of the brain, then a micro-surgical technique can be adapted in order to remove the adenomas in a transsphenoidal process.

Death may result with development of a locally aggressive pituitary tumor.

Morbidity from the disease can occur due to pituitary tissue compression or replacement, and compression of structures that surround the pituitary fossa: The tumor can also compress the optic apparatus, disturb cerebrospinal fluid flow, meningitis, and testicular enlargement in rare cases.

Not utilizing bilateral adrenalectomy as the treatment for Cushing’s disease, has decreased the risk of patients presenting with Nelson’s syndrome.

The most utilized technique for Nelson’s syndrome has been transsphenoidal surgery.

In addition, pharmacotherapy, radiotherapy, and radiosurgery have been utilized accompanying a surgical procedure.

Incidence after adrenalectomy ranges from 15-30%.

Prior pituitary irradiation after bilateral adrenalectomy is protective of the development of Nelson’s syndrome.