Lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) is any form of gastrointestinal bleeding in the lower gastrointestinal tract.

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) is any form of gastrointestinal bleeding in the lower gastrointestinal tract.

LGIB accounts for 30–40% of all gastrointestinal bleeding and is less common than upper gastrointestinal bleeding: UGIB accounts for 100–200 per 100,000 cases versus 20–27 per 100,000 cases for LGIB.

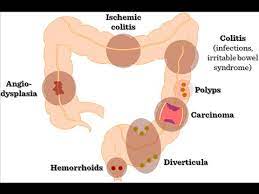

Approximately 85% of lower gastrointestinal bleeding involves the colon.

10% of GI bleeds are actually upper gastrointestinal bleeds, and 3–5% involve the small intestine, despite appearing as lower GI bleeds.

A lower gastrointestinal bleed is bleeding originating distal to the ileocecal valve, which includes the colon, rectum, and anus.

A middle gastrointestinal bleeding is from the ligament of Treitz to the ileocecal valve, and lower gastrointestinal bleeding which involves a bleed anywhere from the ileocecal valve to the anus.

The stool of a person with a lower gastrointestinal bleed is a good, but fallible, indication of where the bleeding is occurring.

Black tarry appearing stools medically referred to as melena usually indicates blood that has been in the GI tract for at least 8 hours.

Melena is four-times more likely to come from an upper gastrointestinal bleed than from the lower GI tract; however, it can also occur in either the duodenum and jejunum, and occasionally the portions of the small intestine and proximal colon.

Bright red stool, called hematochezia, is the sign of a fast moving active GI bleed.

The bright red or maroon color is due to the short time taken from the site of the bleed and the exiting at the anus.

The presence of hematochezia is six-times greater in a LGIB than with a UGIB.

Occasionally, LGIB will not present with any signs of internal bleeding, especially if there is a chronic bleed with ongoing low levels of blood loss.

The possible causes of a LGIB:

Diverticular disease — diverticulosis, diverticulitis Colitis Ischaemic colitis Radiation colitis Infectious colitis Pseudomembranous colitis E. coli O157:H7 Shigella Salmonella Campylobacter jejuni Hemorrhoids Neoplasm — such as colorectal cancer Angiodysplasia Bleeding from a site where a colonic polyp was removed Inflammatory bowel disease such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis Rectal varices Coagulopathy — specifically a bleeding diathesis Anal fissures Rectal foreign bodies Mesenteric ischemia NSAIDs Entamoeba histolytica

Diagnosis:

If an upper GI source is suspected, an upper endoscopy should be performed first.

Lower gastrointestinal series evaluation can be performed with anoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, rarely barium enema, and various radiologic studies.

The history focuses on factors that could be associated with potential causes:

blood coating the stool suggests hemorrhoidal bleeding.

blood mixed in the stool implies a more proximal source of bleeding

bloody diarrhea and tenesmus is associated with inflammatory bowel disease

bloody diarrhea with fever and abdominal pain especially with recent travel history suggests infectious colitis

pain with defecation occurs with hemorrhoids and anal fissure

change in stool caliber and weight loss is concerning for colon cancer

abdominal pain can be associated with inflammatory bowel disease, infectious colitis, or ischemic colitis

painless bleeding is characteristic of diverticular bleeding, arteriovenous malformation (AVM), and radiation proctitis

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use is a risk factor for diverticular bleeding and NSAID-induced colonic ulcer

recent colonoscopy with polypectomy suggests postpolypectomy bleeding.

Evaluation includes: history of symptoms of hemodynamic compromise, dyspnea, chest pain, lightheadedness, and fatigue.

Orthostatic hypotension implies at least a 15% loss of blood volume and suggests a severe bleeding episode.

Physical examination for abdominal tenderness, masses, and enlargement of the liver and spleen, inspection of the anus, palpation for rectal masses, characterization of the stool color, and a stool guaiac test to evaluate for the presence of blood.

Laboratory findings

Blood tests that should be performed: complete blood count, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, electrolytes, and typing and cross-matching for transfusion of blood products.

A clotting abnormality and low platelet concentration in the blood should be immediately corrected if possible.

Platelets should be maintained above 50,000/mL and clotting abnormalities should be corrected with vitamin K or fresh frozen plasma.

The full effect of vitamin K is not obtained for 12–24 hours, unlike fresh frozen plasma which immediately reverses clotting abnormalities.

The intravenous formulation of vitamin K reverses coagulopathy more quickly and may be used in cases of severe bleeding..

The effects of fresh frozen plasma last about 3–5 hours and large volumes (> 2–3 L) may be required to completely reverse clotting abnormalities, depending on the initial prothrombin time.

Anoscopy is useful only for diagnosing bleeding sources from the anorectal junction and anal canal, including internal hemorrhoids and anal fissures.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy uses a 65-cm long sigmoidoscope that visualizes the left colon.

The diagnostic yield of flexible sigmoidoscopy in acute lower GI bleeding is only 9%.

The role of anoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy with acute lower GI bleeding is limited, as most patients should undergo colonoscopy.

Colonoscopy is the test of choice in the majority of patients with acute Lower GI bleeding.

Colonoscopy can be both diagnostic and therapeutic.

The diagnostic accuracy of colonoscopy in lower GI bleeding ranges from 48% to 90%.

The immediate colonoscopy increases diagnostic yield.

The presence of fresh blood in the terminal ileum is presumed to indicate a non colonic source of bleeding.

The complication rate of colonoscopy in acute lower GI bleeding is 1.3%.

About 2–6% of colonoscopy preparations in acute lower GI bleeding are poor.

For patients with hemodynamic instability and hematochezia presenting within four hours of onset CT angiography is the suggested initial diagnostic test.

CT angiography has replaced colonoscopy as the initial test for patients with hemodynamically significant lower G.I. bleed.

Management:

In most cases the bleeding will resolve spontaneously.

Endoscopic evaluation with a colonoscopy (and possibly an esophagogastroduodenoscopy to exclude an UGIB) should typically occur within 24 hours of hospital presentation.

Stopping any aspirin is recommended.

Dual antiplatelet therapy should continue if the person with a LGIB underwent stenting of the heart’s coronary arteries within the last 30 days or a recent acute coronary syndrome episode within 90 days of the LGIB event.

Surgical intervention is warranted in cases of LGIB that persist despite attempts to stop the bleeding with endoscopic or interventional radiology interventions.

For patients with hemodynamic instability, hematochezia and a CT angiography that is positive requires referral to an interventional radiologist for transcatheter angiography and possible embolization.