Also known as epitrochlear bursitis, lateral epicondylitis, olecranon bursitis, and epicondylitis.

Also known as epitrochlear bursitis, lateral epicondylitis, olecranon bursitis, and epicondylitis.

Refers to soreness or pain on the lateral side of the upper arm near the elbow.

Patients present with gradual onset of pain in the absence of trauma.

Caused by small tears in the tendon, leading to irritation and pain where it is attached to the bone.

A tendinopathy, characterized by the insidious onset of lateral elbow pain, usually in the absence of trauma.

The incidence of lateral epicondylitis is 3.4 cases per thousand person years and is similar among men and women; in varying studies estimated the condition affects 1 to 3% of adults.

The highest prevalence among persons: 40 to 49 years of age, followed by 50 to 59 years of age.

Pathogenesis is unknown.

Thought to be caused by chronic degenerative changes at the origin of the elbow extensor tendons with pathologic evaluation, showing infiltration of fibroblasts, vascular hyperplasia, disorganized collagen, all termed, angiofibroblastic tendinitis.

Recent studies showed higher levels of inflammatory cytokines, specifically interleukin 1-alpha and tumor necrosis factor, with greater number of macrophages in the epicondylar tendon tissue.

More prevalent in individuals over 40, where there is about a 4-fold increase among men and 2-fold increase among women.

Strongly linked to racquet associated sports, but can also be caused by swimming, climbing, manual work, playing guitar and similar instruments, as well as other activities of daily living.

Repetitions injure the tendons that connect the extensor supinator muscles, which rotate and extend the forearm, to the olecranon process.

Repeatedly mis-hitting a tennis ball in causes trauma to the elbow joint and may contribute to contracting the condition.

Typically occurs as a result of over use during work or sports, classically racquet sports.

An overuse injury occurring at the common extensor tendon that originates from the lateral epicondyle.

Pain radiates from the lateral forearm.

The most common findings on physical exam: tenderness at the lateral epicondyle of the distal humerus and weakness of pain with resisted wrist extension (Thomsen test).

Weakness, numbness, and stiffness and tenderness are very common with tennis elbow.

Four stages of lateral epicondylitis occur.

Inflammatory changes that are reversible

Nonreversible pathologic changes to origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle

Rupture of ECRB muscle origin

Secondary changes such as fibrosis or calcification.

Permanent damage begins at Stage 2.

In tennis players, about 40% report current or previous problems with their elbow.

24% of tennis athletes under the age of 50 report that the tennis elbow symptoms are severe and disabling, while 42% over those aged of 50 did so.

More women (36%) than men (24%) complain of severe and disabling. symptoms.

Tennis elbow is more prevalent in individuals over 40, where there is about a four-fold increase among men and two-fold increase among women.

It has an increased incidence with increased playing time being greater for respondents under 40.

Individuals over 40 who played over two hours doubled their chance of injury.

Those under 40 increased it 3.5 fold compared to those who played less than two hours per day.

Pain occurs when the arm is fully extended.

Symptom onset is generally gradual.

About 2% of people are affected.

Those 30 to 50 years old are most commonly affected.

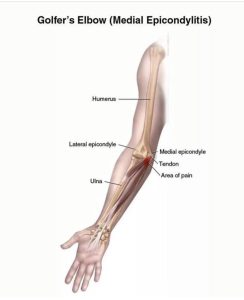

It is a similar condition that affects the inside of the elbow, golfer’s elbow.

The acute pain that a person might feel occurs when they fully extend their arm.

Factor common to this process is overexertion, and repetitive motion.

Duration of pain is less than 1 to 2 years.

It is caused by the excessive use of the muscles of the back of the forearm.

It is a very common type of overuse injury.

It can occur both from chronic repetitive motions of the hand and forearm, and from trauma to the same areas.

Trauma such as direct blows to the epicondyle, a sudden forceful pull, or forceful extension cause more than half of these injuries.

It is due to excessive use of the muscles of the back of the forearm.

Pain associated with gripping and extension movements of the wrist.

Activities that involve repetitive twisting of the wrist can lead to this condition, so that painters, plumbers, construction workers, cooks, and butchers are increased risk.

Risk factors for tennis elbow: Smoking, obesity, and high physical load.

The association with repetitive or forceful use of the arm remains controversial.

This condition may also be due to constant computer keyboard use,

Direct injury to the elbow , sudden pull or forceful extension also associated processes.

Degenerative, non-inflammatory, chronic changes at the origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle.

Diagnosis is made by clinical signs and symptoms: With the elbow fully extended, there is tenderness over the origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle from the lateral epicondyle, and there is pain with passive wrist flexion and resistive wrist extension.

Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms.

Medical imaging used primarily to rule out other potential causes, and his minimal benefit in diagnosis.

Diagnostic imaging is not recommended for evaluation since it is generally a necessary and findings are non-specific.

Differential diagnosis:

Osteochondritis dissecans,

Osteoarthritis,

Radiculopathy: radial tunnel syndrome

X-rays can confirm and distinguish from other causes of pain, such as fracture or arthritis.

Medical ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can aid in diagnosis.

MRI may demonstrate fluid and swelling in the affected region in the elbow.

In some cases symptoms resolve without any treatment within six to twenty-four months.

Evidence suggests that it typically resolves without intervention.

In the study of 72 orthopedic surgeons with lateral epicondylitis, only a minority received any treatment, none had surgery, and 97% had resolution of symptoms within two years.

Choosing no intervention is a reasonable decision, and the use of the affected arm with lifting and exercise does not negatively affect the course of the condition.

If left untreated can lead to chronic pain.

Treatment: non-invasive treatment for pain management is rest.

A wrist brace can also be worn to keep the wrist in flexion, relieving the extensor muscles and allowing rest. Ice, heat, ultrasound, steroid injections, and compression to help alleviate pain.

An exercise therapy is important to prevent injury in the future.

Preventative tennis elbow exercises should be low velocity, and weight should increase progressively.

Stretching the flexors and extensors is helpful, as are strengthening exercises. Massage can also be useful, focusing on the extensor trigger points.

The first step in treatment is rest of the arm and avoiding the activity that caused symptoms for at least 2 – 3 weeks.

Treatment:

Decreasing activities that bring on the symptoms.

Physical therapy

Pain medications such as NSAIDS or acetaminophen.

A brace over the upper forearm may also be helpful.

Physical therapy, including stretching, strengthening, ultrasound, postural, work, and deep tissue massage may help some patients, but overall metaanalysis show no significant benefits of physiotherapy.

If the condition does not improve with above measures, corticosteroid injections or surgery may be recommended.

Gucocorticoid injections have shown short term pain relief, but long-term outcomes may be worse with regard to pain and function compared with wait-and-see approach.

Histological studies show decrees collagen production in fibroblast viability, intending to shoot after glucocorticoid injection, suggesting a possible mechanism for adverse outcomes.

Platelet rich plasma injections have not demonstrated significant difference compared with saline or glucocorticoid injections.

Many people improve within one month to two years.

Findings: Pain on the outer part of the elbow, the lateral epicondyle.

Point tenderness over the lateral epicondyle.

Pain from gripping and movements of the wrist, especially wrist extension as turning a screwdriver and lifting movements.

Symptoms include: radiating pain from the outside of the elbow to the forearm and wrist, pain during extension of wrist, weakness of the forearm, a painful grip while shaking hands or torquing a doorknob, and not being able to hold relatively heavy items in the hand.

The pain is similar to golfer’s elbow, but the latter occurs at the medial side of the elbow.

Since histological findings reveal noninflammatory tissue, the term lateral elbow tendinopathy is the most appropriate terminology.

Tennis elbow is a type of repetitive strain injury.

It results from tendon overuse and failed healing of the tendon.

The extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle plays a key role in TE.

Aspects of tennis that may cause tennis elbow: a backhand with your elbow, excessive pronation of the forearm when putting topspin on a forehand, and excessive flexion of the wrist on a serve can all greatly lead to tennis elbow.

Events that can be improved in lowering risks: racquet type, grip size, string tension, type of court surface, and ball weight.

Histological findings include granulation tissue, micro-rupture, degenerative changes, and but no traditional inflammation.

Ultrasound of the lateral elbow displays thickening and heterogeneity of the common extensor tendon, consistent with tendinosis, calcifications, intrasubstance tears, and marked irregularity of the lateral epicondyle.

There is no evidence of an acute, or a chronic inflammatory process.

Tendon degeneration, replaces normal tissue with a disorganized arrangement of collagen.

It is a tendinopathy rather than tendinitis.

Diagnosis is made by clinical signs and symptoms that are discrete and characteristic.

When the elbow fully extended, the patient feels points of tenderness over the affected point on the elbow.

The most common location of tenderness is at the origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle.

Pain exists with passive wrist flexion and resistive wrist extension, known as Cozen’s test.

X-rays can distinguish other possibilities of existing causes of pain: that are fracture or arthritis, calcifications can be at the the extensor muscles attach to the lateral epicondyle.

MRI screening confirms the presence of excess fluid and swelling in the affected region in the elbow.

Lateral epicondylitis caused by playing tennis, increases with number of playing years and with poor technique.

A higher competitive level of the athlete also affects the incidence of tennis elbow.

Preventing tennis elbow:

Decrease playing time.

Preserving good physical shape.

Strengthening the muscles of the forearm: (pronator quadratus, pronator teres, supinator muscle) and Extensor Carpi Radialis Longus and Brevis

the upper arm: (biceps, triceps)

and the shoulder (deltoid muscle) and upper back (trapezius).

Increased muscular strength increases stability of joints such as the elbow.

Avoid any repetitive lifting or pulling of heavy objects.

Proper weight distribution in the racket is thought to be a more viable option in negating shock.

In some cases symptoms resolve without any treatment, within six to 24 months.

Tennis elbow left untreated can lead to chronic pain.

Short-term analgesic effect of manipulation techniques may allow more vigorous stretching and strengthening exercises, resulting in a better and faster recovery process of the affected tendon in lateral epicondylitis.

Low level laser therapy, administered to the lateral elbow tendon insertions, may result in short-term pain relief and less disability.

Orthosis is a device externally used on the limb to improve the function or reduce the pain, and wrist extensor orthosis reduces the overloading strain at the lesion area

Types of orthoses: counterforce elbow orthoses and wrist extension orthoses.

Both type of orthoses improve the hand function and reduce the pain in people with tennis elbow.

The evidence for anti-inflammatories is anecdotal with only limited studies showing a benefit.

Evidence is poor for long term improvement from corticosteroids, botulinum toxin, prolotherapy or other substances.

In recalcitrant cases surgery may be an option.

Approximately 2 to 4% of patients have persistent pain, regardless of treatment and undergo surgery: it is recommended to minimal 6 to 12 months of persistent symptoms before surgery is considered.

Surgical processes include:

Lengthening, release, debridement, or repair of the origin of the extrinsic extensor muscles of the hand at the lateral epicondyle.

Rotation of the anconeus muscle

Denervation of the lateral epicondyle

Decompression of the posterior interosseous nerve

Surgical techniques include open surgery, percutaneous surgery or arthroscopic surgery, with equal efficacy.

Surgical complications include infection, damage to nerves and inability to straighten the arm.

Surgical studies do not show that surgery is any more effective than other treatments.

A research trial showed that surgery was no more effective than sham surgery.

While there is an initial response, relapse occurs in 25% to 50% of cases and/or is associated with prolonged, moderate discomfort in 40%.

Adding ice on the outside of your elbow 2 – 3 times a day.

Exercises using a rubber bar is highly effective at eliminating pain and increasing strength.

Joint mobilization with movement directed at the elbow reduces pain and improves function.

NSAIDs relieve lateral elbow pain, however they provide no improvements in functional outcome.

Injected NSAIDs may be better than oral form of administration.

Corticosteroid injection are effective in the short term, but are of little benefit after a year.

At the 26-week and 1-year follow-ups, patients who underwent the steroid injection were less likely to have complete recovery or much improvement and more likely to have recurrence of the pain compared with those who underwent placebo injection.

In the long run they not only have limited benefit but may actually have a negative effect.

In a randomized trial with 1 year follow up, a recurrence was found in 72% of patients receiving corticosteroid injections compared with only 8% after physiotherapy (Bisset L et al).

Long-term effects of corticosteroid injection combined with physiotherapy are not known.

In a placebo-controlled study, a single injection of corticosteroids medication was associated with poor long-term outcome and higher recurrence rate one year in patients with unilateral lateral epicondylalgia (Coombes Bk et al).

In the above study the addition of physiotherapy to placebo or to corticosteroid injection did not result in any significant differences.

Prolotherapy, utilizing a fibrosing agent such as 50% glucose or autologous plasma injected into the space surrounding a tendon, strengthens it and may be an effective treatment, to improve pain and function.

In recalcitrant cases, surgery may be efficacious.

Initially, the response to therapy is common, but relapse rate is as high as 18-50% and may be associated with pain .