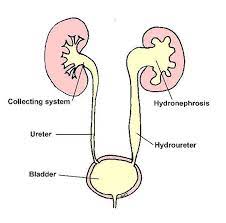

Hydronephrosis describes the dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces as a result of obstruction to urine flow downstream.

Hydronephrosis describes the dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces as a result of obstruction to urine flow downstream.

Alternatively, hydroureter describes the dilation of the ureter, and hydronephroureter describes the dilation of the entire upper urinary tract, of both the renal pelvicalyceal system and the ureter.

The signs and symptoms of hydronephrosis depend upon whether the obstruction is acute or chronic, partial or complete, unilateral or bilateral.

Hydronephrosis that occurs acutely with sudden onset can cause intense pain in the flank known as a renal colic.

Hydronephrosis that develops gradually over time will generally cause either a dull discomfort or no pain.

Nausea and vomiting may also occur with hydronephrosis

An obstruction that occurs at the urethra or bladder outlet can cause pain and pressure resulting from distension of the bladder.

Blocking the flow of urine will commonly lead to urinary tract infections which can lead to further development of stones, fever, and blood or pus in the urine.

If complete obstruction occurs, a postrenal kidney failure or obstructive nephropathy may follow.

Blood tests may show elevated urea or creatinine levels or electrolyte imbalances such as hyponatremia or hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis.

Urinalysis may indicate an elevated pH due to the secondary destruction of nephrons within the affected kidney, which impairs acid excretion.

Physical examination in a thin patient may detect a palpable abdominal or flank mass caused by the enlarged kidney.

Hydronephrosis is the result of any of several abnormalities:

Structural abnormalities of the junctions between the kidney, ureter and bladder that lead to hydronephrosis can occur during fetal development.

Some of these congenital defects have been identified as inherited conditions.

Structural abnormalities could be caused by injury, surgery, or radiation therapy.

The most common causes of hydronephrosis in children are anatomical abnormalities including vesicoureteral reflux, urethral stricture, and stenosis.

The most common cause of hydronephrosis in young adults is kidney stones.

In older adults, the most common cause of hydronephrosis is benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH), or intrapelvic neoplasms such as prostate cancer.

Compression of one or both ureters can also be caused by other developmental defects as an abnormally placed vein, artery, or tumor.

Bilateral compression of the ureters can occur during pregnancy due to enlargement of the uterus.

Sources of obstruction include kidney stones, blood clots or retroperitoneal fibrosis.

The obstruction may be either partial or complete, and can occur anywhere from the urethral meatus to the renal calyces.

Hydronephrosis can also result from the retrograde flow of urine from the bladder back into the kidneys via vesicoureteral reflux, which can be caused by some of the factors listed above as well as compression of the bladder outlet into the urethra by prostate enlargement or fecal impaction in the rectum, as well as abnormal contractions of bladder detrusor muscles resulting from neurological dysfunction or other muscular disorders.

Hydronephrosis is caused by obstruction of urine before the renal pelvis.

The obstruction causes dilation of the nephron tubules and flattening of the lining of the tubules within the kidneys which in turn causes swelling of the renal calyces.

In acute hydronephrosis full recovery of kidney function is seen.

With chronic hydronephrosis, permanent loss of kidney function is seen even once obstruction is removed.

Obstruction that occurs anywhere along the upper urinary tract will lead to increased pressure within the structures of the kidney due to the inability to pass urine from the kidney to the bladder.

Common causes of upper tract obstruction include obstructing stones and ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction caused by intrinsic narrowing of the ureters or an overlying vessel.

Obstruction that occurs in the lower urinary tract can also cause this increased pressure through the reflux of urine into the kidney.: Common causes include bladder dysfunction of neurogenic bladder and urethral obstruction, such as posterior urethral valves in male infants, or compression as with prostatic hypertrophy in older male adults.

In pregnancy, rotation to the right of the uterus can cause compression on the right ureter, thus making hydronephrosis more common in right kidney than left kidney.

Hormones such as estrogen, progestrerone, and prostaglandin can cause ureter dilatation, thus causing hydronephrosis despite the absence of visible obstruction along the urinary tract.

Prenatal diagnosis of hydronephrosis is possible most cases in pediatric patients are incidentally detected by routine screening ultrasounds obtained during pregnancy.

Approximately half of all prenatally identified hydronephrosis is transient, and resolves by the time the infant is born.

In 15%, the fetal hydronephrosis persists but is not associated with urinary tract obstruction.

For these children, regression of the hydronephrosis occurs spontaneously, usually by age 3.

In the remaining 35% of cases of prenatal hydronephrosis, a pathological condition can be identified postnatally.

Diagnostic workup depends on the age of the patient, as well as whether the hydronephrosis was detected incidentally or prenatally or is associated with other symptoms.

In cases of severe unilateral hydronephrosis, the overall kidney function may remain normal since the unaffected kidney will compensate for the obstructed kidney.

Urinalysis is usually performed in hydronephrosis to determine the presence of blood (kidney stones) or signs of infection, such as a positive leukocyte esterase or nitrite.

Impaired concentrating ability or elevated urine pH due to distal renal tubular acidosis are also commonly found due to tubular stress and injury.[

Imaging studies, such as an intravenous pyelogram (IVP), renal ultrasonography, CT, or MRI, are investigations used in determining the presence and/ or cause of hydronephrosis.

An ultrasound allows for visualisation of the ureters and kidneys and determines the presence of hydronephrosis and / or hydroureter.

An IVP is useful for assessing the anatomical location of the obstruction.

Antegrade or retrograde pyelography will show similar findings to an IVP but offer a therapeutic option as well.

Doppler ultrasound tests in association with vascular resistance testing helps determine how a given obstruction is effecting urinary functionality in hydronephrotic patients.

The location of obstruction can be determined with pressure perfusion test, wherein the collecting system of the kidney is accessed percutaneously, and the liquid is introduced at high pressure and constant rate of 10ml/min while measuring the pressure within the renal pelvis.

A rise in pressure above 22 cm H2O suggests that the urinary collection system is obstructed.

It is recommended that a neonate born with untreated in utero hydronephrosis receive a renal ultrasound within two days of birth.

A renal pelvis greater than 12 mm in a neonate is considered abnormal and suggests significant dilation and possible abnormalities such as obstruction or morphological abnormalities in the urinary tract.

In the case of renal colic, where this a one sided loin pain usually accompanied by a trace of blood in the urine, the initial investigation is usually a spiral or helical CT scan.

Many stones are not visible on plain X-ray or IV urogram but 99% of stones are visible on CT and therefore CT is a common choice of initial investigation.

For incidentally detected prenatal hydronephrosis, the first study to obtain is a postnatal renal ultrasound, as many cases of prenatal hydronephrosis resolve spontaneously.

A voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) is also typically obtained to exclude the possibility of vesicoureteral reflux or anatomical abnormalities such as posterior urethral valves.

Grading hydronephrosis in adults as well:

Grade 0 – No renal pelvis dilation.

This means an anteroposterior diameter of less than 4 mm in fetuses up to 32 weeks of gestational age and 7 mm afterwards.

In adults, cutoff values for renal pelvic dilation have been defined differently by different sources, with anteroposterior diameters ranging between 10 and 20 mm.

About 13% of normal healthy adults have a transverse pelvic diameter of over 10 mm.

Grade 1 (mild) – Mild renal pelvis dilation (anteroposterior diameter less than 10 mm in fetuses without dilation of the calyces nor parenchymal atrophy

Grade 2 (mild) – Moderate renal pelvis dilation (between 10 and 15 mm in fetuses including a few calyces

Grade 3 (moderate) – Renal pelvis dilation with all calyces uniformly dilated. Normal renal parenchyma

Grade 4 (severe) – As grade 3 but with thinning of the renal parenchyma

Treatment of hydronephrosis focuses upon the removal of the obstruction and drainage of the urine that has accumulated behind the obstruction.

Acute obstruction of the upper urinary tract is usually treated by the insertion of a nephrostomy tube.

Chronic upper urinary tract obstruction is treated by the insertion of a ureteric stent or a pyeloplasty.

Lower urinary tract obstruction such as that caused by bladder outflow obstruction secondary to prostatic hypertrophy is usually treated by insertion of a urinary catheter or a suprapubic catheter.

Surgery is not required in all prenatally detected cases.

The prognosis of hydronephrosis depends on the condition leading to hydronephrosis, whether one or both (bilateral) kidneys are affected, the pre-existing kidney function, the duration of hydronephrosis being acute or chronic, and whether hydronephrosis occurred in developing or mature kidneys.

Permanent kidney damage can occur from prolonged hydronephrosis secondary to compression of kidney tissue and ischemia.

Unilateral hydronephrosis caused by an obstructing stone will likely resolve when the stone passes, and the likelihood of recovery is excellent.

Severe bilateral prenatal hydronephrosis will likely carry a poor long-term prognosis, because obstruction while the kidneys are developing causes permanent kidney damage even if the obstruction is relieved postnatal.

Hydronephrosis can be a cause of pyonephrosis, which is a urological emergency.