Coronary artery anomalies refers to variations of the coronary circulation, affecting <1% of the general population.

Coronary artery anomalies refers to variations of the coronary circulation, affecting <1% of the general population.

Symptoms include chest pain, shortness of breath and syncope.

A majority of deaths associated with coronary artery anomalies are thought to occur with exercise.

Cardiac arrest may be the first clinical presentation of a coronary artery anomaly.

In athletes, CAA may manifest as syncope, presyncope, or at times angina.

Several types exist.

Coronary arteries are vessels supplying blood and nutrients to the heart muscle.

Coronary arteries arise from ostia, openings of the aorta at the upper third or middle third of the sinuses of Valsalva.

The walls of coronary arteries consist of three layers: the tunica intima or inner layer (possible site of lipid deposits and fibrosis, during life), the tunica media (a smooth muscle layer whose tone is modulated by the nervous system, influencing vessel diameter and resistance) and adventitia (where nervous endings are located).

Normally, the initial portion of coronary arteries lies onto the external surface of the heart (epicardium) where fat deposits tend to form during life.[citation needed]

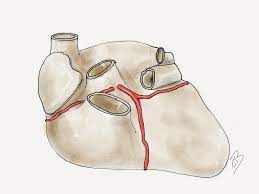

In normal anatomy, three essential coronary arteries are identified: right coronary artery (RCA), left anterior descending artery (LAD) and left circumflex artery (LCx).

LAD and LCx usually originate from the bifurcation of a common vessel known as left main trunk or left coronary artery (LM or LCA).

Coronary arteries are identified according to the myocardial territory they feed:

1) the LAD supplies the anterior interventricular septum and anterior left ventricular free wall;

2) the LCx supplies the posterolateral left ventricular free wall;

3) the RCA supplies the right ventricular free wall;

There is a certain degree of variability in coronary artery anatomy among individuals.

The posterior descending artery, providing blood flow to the infero-posterior wall of the heart, originates from the RCA in 70-90% of individuals, whereas in 10-15% cases it originates from the LCx.

Coronary vessels diameter progressively decreases proceeding from their origin to the periphery.

Capillaries represent the smallest peripheral vessels of the coronary tree that lack muscular tissue and are responsible for oxygen and nutrients exchange within the myocardium.

Normal variant: any morphological feature observed in >1% of an unselected population.

An alternative, unusual but benign morphological feature identified in >1% of the same population: left main is absent in 1-2% of the general population with LAD and LCx originating from separate ostia.

A coronary artery anomaly (CAA): a morphological feature seen in <1% of that population, capable of causing dysfunction

The prevalence of coronary artery anomaly is considered to affect <1% of the general population.

An MRI screening of more than 5000 young children suggested that coronary artery anomalies are present in 0.45% of the US population, or approximately 1.3 million people.

There are anomalies at the ostium, such as congenital ostial atresia or stenosis or anomalous origin of a coronary artery from the opposite sinus [ACAOS]: right coronary artery anomalous origin from the opposite sinus [R-ACAOS] and left coronary artery origin from the opposite sinus [L-ACAOS]); anomalies at the mid segments (such as myocardial bridge [MB]); anomalies at the termination (such as coronary arteriovenous fistulas).

Anomalous origin of a coronary artery from the opposite sinus are relevant on a clinical level due to a significant association with sudden cardiac death, if they are accompanied by intramural course.

The stenosis of an intramural proximal segment, lateral compression and spastic hyperreactivity are the mechanisms that have been linked to clinical manifestation.

Autonomic and/or endothelial dysfunction may occur and induce spasm and/or thrombosis at anomalous sites.

Coronary narrowing is the main process implied with coronary anomaly and it may result in symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations, cardiac arrhythmias, and syncope.

Acute angulation of an aberrant coronary origin, dynamic compression by adjacent structures, and presumed obstructive ischemia are proposed mechanisms of angina and sudden cardiac death that occur in the context of exercise.

Coronary artery anomalies are usually silent for many years and the first clinical manifestation is sudden cardiac death

due to malignant arrhythmias.

This occurs typically after strenuous physical exertion, when arterial compression is more severe, and cardiac work is maximal.

19-33% of sudden deaths in young athletes are due to coronary artery anomalies.

In a large autopsy study involving military recruits, one in three cases of sudden death occurred in this population was found to be caused by CAAs.

Clinical manifestations can be found in non-athletic, older individuals and are commonly associated with hypertension and aortic dilatation with worsening degree of compression.

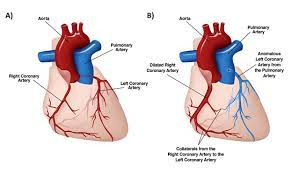

The right coronary artery normally arises from the right sinus of Valsalva of the aortic root, and the left coronary artery arises from the left sinus of Valsalva.

Most cardiac sudden deaths are associated with the left coronary artery arising from the right Valsalva sinus,and then coursing between the pulmonary artery and the aorta.

Coronary artery anomalies can be detected by means of transthoracic echocardiogram of the coronary origins, but CT angography is increasingly available and the test of choice.

L-ACAOS-IM- (Anomalous coronary artery from opposite sinus)-intramural type is seen in 0.1% of young children and, among coronary anomalies, it has the highest probability of clinical association with sudden cardiac death following physical exercise.

Several L-ACAOS types exist:

prepulmonic (L-ACAOS-PP): origin of the LCA (or only the LAD) from the right sinus of Valsalva (RSV) with an epicardial course anterior to the pulmonary outflow tract.

Prepulmonic (L-ACAOS-PP). does not usually cause stenosis nor requires intervention.

Subpulmonary, infundibular or intraseptal (L-ACAOS-SP): originates from the RSV, initially runs inter-arterially then intramyocardially inside in the ventricular septum and finally epicardially in the anterior interventricular groove.

This anomaly is considered benign.

Retroaortic (L-ACAOS-RA): origin of the LCA or the only LCx from the RSV or from the RCA, running behind the aortic root and at the central fibrous mitro-aortic septum.

It is considered as a benign anomaly.

Retrocardiac (L-ACAOS-RC) – LCA originates from the RCA at the atrioventricular groove – or wrap-around the apex is generally benign.

R-ACAOS-IM is observed in a higher percentage of cases (0.35% of adolescents) than L-ACAOS-IM but is less likely to be associated with sudden cardiac death in athletes.

Varieties of R-ACAOS such as prepulmonic, retroaortic and intraseptal can occur and are considered generally benign.

The most frequent symptomatic coronary anomaly in infants and young children is anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery.

The anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery may cause acute myocardial infarction at neonatal age and requires emergent surgery at the time of diagnosis.

Anomalies at the mid segments include myocardial bridges, affecting >1% of the clinical population.

Anomalies at the mid segments include myocardial bridges characterized by an intramyocardial course of coronary arteries within the muscle fibers.

Most myocardial bridges are benign and do not require any intervention.

This may present this is generally due to localized endothelial dysfunction with a tendency to spasm.

Most myocardial bridges are benign and do not require any intervention.

Coronary artery aneurysms are defined as a > 50% increase of the vessel diameter.

Some cases are congenital/idiopathic, but most are secondary to atherosclerosis or Kawasaki disease.

Potential complications include localized thrombosis, distal embolization, rupture, or late lipid deposits.

Coronary arteriovenous fistulas are anomalies at the termination consisting of an anomalous connection of coronary arteries to coronary veins, veins of the pulmonary or systemic circulations, or to any cardiac cavity.

Smaller fistulas are usually benign, and only severe cases can be complicated by aneurysmatic dilatation with potential thrombosis and distal embolization, volume overload or blood steal from arterial circulation and subsequent ischemia.

Treatment is generally not required.

Carriers of coronary artery anomalies may receive positive results following stress/imaging tests.

Routine screening of high-risk populations of individuals participating in competitive sports should be generally encouraged in clinical practice of sports cardiologists.

Echocardiography use for CAAs screening is limited because its diagnostic sensitivity is highly dependent on the operator’s skills and is significantly lower in larger individuals (>40 kg).

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) is an excellent tool to identify coronary artery anomalies with a significantly higher diagnostic accuracy than standard echocardiography.

Coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) provides precise assessment of coronary anatomy, course and degree of stenosis, but its clinical use for screening is strongly limited by its cost, the need for ionizing radiation, and intravenous contrast.

Assessment of the severity of stenosis is best achieved by intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) imaging.

IVUS consists of cross-sectional imaging of coronary arteries in a catheterization laboratory by advancing a thin probe inside the vascular lumen, obtaining precise in-vivo information about degree of area stenosis in different arterial segments, providing a solid basis for treatment strategies.

CAAs include a wide spectrum of entities with different severity.

Treatment:

Criteria for intervention in ACAOS-IM are:

-symptoms of effort-related chest pain, shortness of breath, syncope or aborted sudden cardiac death.

-positive treadmill stress test, ideally by nuclear technology, in the correct dependent myocardial territory, in the presence of intramural course.

For athletes, treatment may be indicated in the absence of the previously mentioned criteria.

Narrowing >50% in comparison to the distal normal segment is generally accepted as a marker of severity in L-ACAOS-IM.

Treatment decisions are based on individual characteristics such as age, symptoms, profession and level of engagement in physical activity.

Observation/pharmacological treatment may be appropriate in selected, low-risk patients.

Unntreated carriers of significant ACAOS should not engage in competitive sports or strenuous activities.

Treatment options for ACAOS-IM9intramural type) include both catheter-based procedures (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]) and surgical interventions.

PCI consists of stent angioplasty of the proximal, intramural segment by placing a stent in order to keep open the narrowed artery.

PCI of R-ACAOS-IM is feasible and successful.

L-ACOS is usually treated with surgery.

Surgery consists of unroofing or denudation of the intramural coronary segment from the aortic wall.

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and reimplantation of the ectopic artery are not indicated.