A systemic immune mediated disorder triggered by dietary gluten in genetically predisposed people.

A systemic immune mediated disorder triggered by dietary gluten in genetically predisposed people.

Caused by ingestion and containing grains such as wheat, rye, and barley in genetically susceptible person.

Permissive genes are present in approximately 30% of the general white population.

A chronic enteropathy of the small bowel.

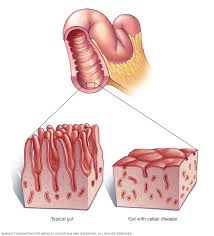

Its hallmark is injury to the small bowel mucosa that causes villous atrophy and results in male absorption of micronutrients, fat soluble vitamins, iron, vitamin B12, and folic acid.

A global disease of both children and adults.

The mean age at diagnosis in the US is 38 years and approximately 20% of patients are diagnosed after age 60 years.

Prevalence ranges from 1:1250 to 1:1500.

Affects 06-1% of the population worldwide.

As many as 6 of 7 cases of celiac disease remain undiagnosed.

Most patients are asymptomatic or have non-classic presentation.

Most cases are unrecognized.

One of the most common lifelong disorders.

Can be a devastating process associated with increased mortality and substantial morbidity.

Has wide geographic differences in prevalence.

A systemic disease that affects persons of any age in many races and different ethnic groups.

Frequency increasing in many developing countries because of westernization of the diet, alteration in wheat production and preparation, and increases in the awareness of the disease.

Seroprevalence as high as 1 in 133 persons in the general population and 1 in 22 among first-degree relatives of patients with celiac disease.

Disease almost 1% of U.S. population (Fasano).

More than 80% of patients remain undetected clinically.

83% of patients are undiagnosed of misdiagnosed.

Commonly presents during early childhood, suggesting the importance of studying early life events to identify triggers of the disease.

Increased intake of gluten during the first five years of life is an independent risk factor for celiac disease and an independent autoimmunity and celiac disease in genetically predisposed children.

Average time to be correctly diagnosed 6-10 years.

Presently prevalence is approximately 1-2% of the general population.

Primarily in Caucasians.

Increased prevalence among women by 1.5 to 2 times compared to men.

Its increased prevalence in women is typical of autoimmune diseases.

Prevalence has increased in developed countries over recent decades.

Increased prevalence among persons who have an affected first degree relative, 10-15%, have type I diabetes, 3-16%, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Sjogren’s syndrome, Down syndrome, 5%, Turner”s syndrome, 3%, IgA deficiency 9%, and other autoimmune disease.

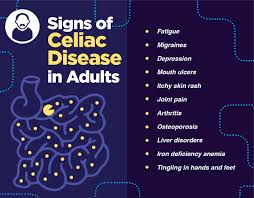

Patients with CD may present with classic features such as short stature, failure to thrive in childhood, delayed puberty, lethargy, and weight loss.

More than 10% of patients with CD are obese.

While gastrointestinal symptoms, diarrhea, flatulence, bloating, abdominal discomfort, and nausea may be seen, 20% of patients may actually report constipation.

CD is associated with the extra intestinal manifestations, such as fatigue, weight loss, dermatitis, herpetiformis, iron deficiency, and osteoporosis.

Rarely, it may present as a life-threatening diarrheal illness with multiple electrolyte disturbances.

Increasing incidence related to improved diagnostic testing and true increase in disease prevalence.

Screening for CD is not recommended in the absence of characteristic signs of symptoms is not recommended.

Diagnostic evaluation incorporates serologic, and histologic data.

HLA-DQ2 haplotype is expressed by the majority of patients, reaching 90%, whereas it is expressed in only one third of the general population.

5% of patients have HLA-DQ8 haplotype, and the remaining 5% of patients have at least one of the two genes encoding DQ2 or DqA1.

DQ2 and DQ 8 haplotypes expressed on antigen presenting cell surfaces can bind to gluten and trigger immune responses, and are necessary for the development of the disease.

CD is strongly associated with HLA-DQ2 (DQA1*05/DQB1*02) and HLA-DQ8 (DQA1*03/DQB1*03).

While DQ2 and DQ8 haplotypes are necessary for the disease they are not sufficient for its development.

Presently (2013), 39 non-HLA genes are associated with a predisposition to the disease.

For the disease to manifest it requires an external trigger, which is gluten, intestinal permeability, gluten modification by enzymes, HLA recognition, immune responses to gluten peptides involving self anigens.

Gluten is required to trigger the disease process, but interplay between genetics and environmental factors regulates the balance between tolerance and I’m immune response.

Intestinal infections, amount and quality of gluten, composition of intestinal microbiota, and infant feeding practice may trigger a switch from tolerance to an immune response to gluten.

Anti-gliadin and anti-endomysial IgA antibody serologies are reasonably effective screening tests with sensitivities ranging from 90-100%.

Blood transglutaminase antibody (tTG) IGA anssays are the first line for diagnosis of celiac disease: has a specificity of 98% and a sensitivity of 89% compared with small bowel biopsy, provided a patient is not following a gluten-free diet at the time of testing and is not IGA deficient.

When the titer of tTG IgA is less than fivefold the limit of normal, celiac disease is ruled out.

In susceptible persons, exposure to gliadin peptides originating from gluten in the diet leads to surface epithelium and lamina propria changes through immune mediated mechanisms involving both innate and adaptive immune systems.

When gliadin reaches the lamina propia, it becomes more immunogenic, with increased interaction between antigen presenting cells.

This immune cell activation and cytokine release causes the histologic changes that are the hallmark of CD.

B lymphocytes produce CD-specific auto antibodies allowing for seologic detection of the disease.

Measurement of IGA anti-endomysial antibodies is nearly 100% specific for active disease but false positive results may occur in other autoimmune diseases, including type I diabetes

Anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA antibody test have sensitivity and specificity higher than 90% and 95%, respectively, equating to positive predictive value of approximately 75% and negative predictive value of approximately 99% in moderate risk populations.

Tissue transglutaminase (tTG) IgA testing is presently initial test of choice.

Serologic screening is recommended for all first-degree family members of patients with celiac disease.

Patients with CD should have first-degree family members tested for CD, which can be done with an IgA TTG antibody test.

Serum IgA anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies is recommended for initial testing of patients without concomitant IgA deficiency.

In patients with IgA deficiency IgG anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies can be measured.

Direct immunofluorescence on skin biopsy reveals granular deposits of IgA at the level of the basal membrane between the dermis and epidermis junction.

Antibodies against epidermal transglutaminase are present in 80% of the cases but are not necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Measurement of the deamidaed gliadin peptide antibodies of the IgG class has a better sensitivity and specificity and measurement of IgG anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies as a screening test for celiac disease in IgA deficient patients.

The sensitivity of serological testing in celiac disease is markedly reduced in patients who are on a gluten restricted diet, and therefore patients should not be on a restricted diet before testing.

5% of patients have negative tTG antibody results.

All serologic tests for CD are less sensitive in children less than 2 years.

2-3% of patients have selective IgA deficiency and such levels should be measured.

Gluten sensitive enteropathy induced by prolamins (gluten) present in wheat, rye and barley.

Individuals are intolerant to gliadin fraction of gluten in wheat, rye and barley.

The classic form of presentation is in early childhood with diarrhea, abdominal pain, malabsorption and nutrient deficiencies.

Children frequently manifest with vomiting, diarrhea, failure to thrive, muscle wasting, irritability and findings of hypoproteinemia.

Wide range of presentation from asymptomatic to fatigue, weight loss, diarrhea and malabsorption.

Median time between seeing a physician because of symptoms and diagnosis is 12 months.

Up to 40% of patients have chronic diarrhea, weight loss, and abdominal distention.

Patients may have iron deficiency with or without anemia, apthous stomatitis, children may have short stature, elevated aminotransaminase levels, chronic fatigue and reduced bone mineral density.

Up to 85% of patients with celiac disease have anemia on presentation.

Anemia in celiac disease is due to malabsorption of iron within the G.I. tract due to villous atrophy in the distal duodenum and jejunum.

Patients have been found to be anemic for up to 12 years prior to establishing a diagnosis, and the degree of villous atrophy is found to predict the higher likelihood of micro nutrient deficiencies.

Rarely associated with dermatitis herpetiformis, gluten ataxia and celiac crisis.

Commonly associated processes with CD include: autoimmune thyroid disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, adrenal insufficiency, various connective tissue disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and Sjögren syndrome, selective IgA deficiency, inflammatory bowel disease, microscopic colitis, autoimmune hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, primary biliary cholangitis, and IgA nephropathy.

Dermatitis herpetiformis is its cutaneous manifestation of CD, and manifests more commonly in men.

Dermatitis herpetiformis skin lesions includes pruritic papulovesicular lesions most often located in the extensor surfaces of elbows, knees, and buttocks.

A dapsone clinical response supports the diagnosis.

The long-term prognosis for CD is excellent with the use of a gluten-free diet.

Clinical response to CD is slow and many patients require dapsone initially to control rash-related symptoms.

Iodine ingestion may precipitate a flare in CD and its use is discouraged.

IgA TTG, along with measurement of total IgA, is the serology of choice for screening patients for CD.

IgA TTG result that is 3 times the upper limit of normal is strong evidence for a diagnosis of CD.

False-positive results are more likely when lower titers are present.

False-positive may be found in the presence of other conditions such as cirrhosis, heart failure, or concurrent autoimmune disease.

A negative TTG result is not sufficient to rule out CD in patients when there is a high suspicion for the disease.

False-negative results are usually due to the initiation of a gluten-restricted diet before testing, coexistent IgA deficiency, or mild enteropathy.

IgA deficiency may be seen in approximately 2% to 3% of patients with CD.

In a patient with suspected IgA deficiency, clinicians could either measure the IgA level or use a combination IgA and IgG serology.

In patients with celiac disease who continue with ingested gluten develop small bowel villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and intraepithelial lymphocytes all of which can be reversed by removal of gluten from the diet.

Seropositivity studies suggest that for each diagnosed case of celiac disease 3-7 persons remain undiagnosed.

Gold standard of diagnosis requires upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsy.

Diagnosis is made in a patient who is genetically predisposed based on the presence of clinical features, positive specific celiac serologic findings, duodenal biopsies that document enteropathy and improvement with a gluten-free diet.

Laboratory work-up for newly diagnosed CD: complete blood cell count, measurement of ferritin, vitamin B12, folate, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase and thyrotropin levels.

In the presence of malabsorption, additional testing should include serum albumin, vitamins A and E, international normalized ratio, copper, and zinc measurements.

Support exists for making a diagnosis of CD without the need for biopsy: appropriate symptomatology and a TTG antibody level greater than 10 times normal, the presence of presence of HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8, and a separate blood sample with a positive endosomial antibody result.

Conditions that histologically mimic CD; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, Helicobacter pylori infection, inflammatory bowel disease.

Celiac disease autoimmunity is characterized by increased TTG antibody or endomysial antibody (EMA) on at least 2 occasions.

A diagnosis of CD is based on the presence of compatible clinical features, positivity of CD-specific serology, small bowel biopsy specimens with characteristic histologic features, and response to a gluten-free diet.

The preferred initial serology is TTG IgA with measurement of total IgA to rule out IgA deficiency.

Increased immunological responsiveness to ingested wheat gliadin, rye, and barley in genetically predisposed individuals.

The diagnostic accuracy of serologic testing and small intestinal histology for CD is severely affected by elimination of gluten from the diet-sensitivity of 16% for IgA TTG after a median of 11 months on a gluten-free diet).

Histopathologic documentation of small intestine enteropathy is considered the criterion to confirm the diagnosis of CD.

Endoscopic findings such as loss of folds, scalloping, fissuring, or cobblestone mucosa lack sensitivity and are not specific for CD49.

Multiple duodenal biopsies are suggested to establish diagnosis of CD, because of the patchy nature of the disease.

It is recommended that two biopsy specimens be obtained from the bulbar duodenum and two from the distal duodenum.

Biopsy specimen show increased intraepithelial lymphocytosis, villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and a chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria.

Therefore, testing for CD should be done when patients are consuming a gluten-containing diet.

Inflammation is induced by the foreign protein gluten, but the disease is a complex autoimmune disorder rather than an allergy because of the presence of tissue transaminase autoantibodies.

The equivalent toxic fractions in rye, barley and possibly oats are secalins, hordeins and avenins, respectively.

Villous atrophy is seen in entities besides CD: medications, autoimmune enteropathy, combined variable immunodeficiency, tropical sprue, and collagenous sprue.

A gluten challenge consists of an exposure to 3-10 g/d of gluten with close monitoring for symptoms and subsequent serologic and/or histologic testing for CD.

A slice of wheat bread typically contains 2 g of gluten.

Strict, adherence to a gluten-free diet, avoiding wheat, barley, and rye is the treatment.

Pure oats are typically safe, but there is the concern for potential cross-contamination.

Gluten reactive T cells proliferate similar to an autoimmune disease.

Small intestine gluten sensitive T cells recognize peptide epitopes when presented in association with DQ2, with activation of T cells causing damage to small intestine.

Gluten is the major protein in wheat, rye, barley and related grains, is poorly digested.

Gluten reaches the intestinal lumen in large polypeptides, and in patients with celiac disease in these gluten peptides pass through the mucosa of the small intestine and into the submucosa.

Submucosal gluten peptides are modified by tissue transglutaminase so that they can bind with high affinity to HLA antigen DQ2 and DQ8 molecules on antigen presenting cells stimulating cell mediated and immunity (Sollid LM et al).

The majority of patients with celiac disease are known to have a particular major histocompatibility complex class II antigen‐presenting receptor, which includes 1 of 2 types of the HLA‐DQ protein, namely, HLA‐DQA1 and HLA DQB1.

Tissue transglutaminase is suggested as the major autoantigen.

Transglutaminase is the antigen for antiendomysial antibody.

Assay of tissue transglutaminase-enzyme has a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 94% in diagnosis.

Approximately 10% of patients have an associated neurologic disease, most often peripheral neuropathy or ataxia, but seizures dementia and psychiatric illness may occur.

Half of adult-onset patients lack prominent gastrointestinal symptoms.

Rash sometimes associated with celiac disease is dermatitis herpetiformis.

Dermatitis herpetiformis an extra intestinal manifestation of gluten enteropathy manifested with a pruritic blistering rash and demonstration of granular immunoglobin IgA in uninvolved skin.

Many patients have iron deficiency anemia.

Patients with CD may be anemic related to iron, folate, or vitamin B12 deficiency.

Iron deficiency anemia is the most common extraintestinal feature of CD.

The prevalence of CD ranges from 3% to 9% in patients with iron deficiency without any G.I. symptoms.

In patients with CD and gastrointestinal symptoms iron deficiency may have prevalence rates as high as 10% to 15%.

CD should be considered in all patients undergoing a work-up for iron deficiency anemia.

May be associated with thyroid disease, cerebral calcifications, Sjögren disease, impaired splenic function, neurologic disorders, ulcerative jejunoileitis and cancer.

In patients with functional asplenia, as evidenced by Howell-Jolly bodies on a peripheral smear, vaccination against encapsulated organisms is appropriate.

Associated with an increased risk for serious infections.

In a Swedish study of 49,829 patients with CD followed for median of 12.5 years, the mortality rate compared with the general population was 9.7 versus 8.6 deaths per 1000 thousand person-years a small but statistically significant increase (Lebwohl B).

Immune system dysfunction is attributed to hyposplenism and B-cell neutrophil impairment.

Asplenia and hyposplenism are known risk factors for overwhelming infection by encapsulated bacteria, and accounts for increased risk for infections with encapsulated bacteria, such as streptococcus pneumoniae.

Patients with celiac disease should receive preventive pneumococcal vaccination, especially between the ages of 15 and 64.

Must be considered with unexplained iron deficiency, B12, folate, hypoalbuminemia, osteomalacia or osteoporosis.

May be related to infertility or recurrent miscarriage.

Men with celiac disease may have reversible infertility.

In men, celiac disease can reduce semen quality and cause immature secondary sex characteristics, hypogonadism and hyperprolactinaemia, which causes impotence and loss of libido.

An effective evaluation for infertility would best include assessment for underlying celiac disease, both in men and women.

T-cell lymphoma, bowel cancer and epilepsy more common in patients with celiac disease.

Can account for short stature in children.

Most patients carry the human leukocyte antigen HLA_DRB1*03 or HLA-DRB1*04.

Disease triggered by persons who carry HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 genes and exposed to dietary gluten.

A 20 fold increase in the risk of clinical symptoms between HLA-DQ2 homozygotes and heterozygotes.

Celiac disease autoimmunity usually develops between ages 4 and 24 months, after weaning, when cereals are initially introduced into the diet.

Suspected that termination of breast feeding before introduction of gluten may be an environmental risk factor.

Type I diabetics and their first-degree relatives have a higher risk of celiac disease.

6-8% of insulin dependent diabetes have concomitant celiac sprue.

Adult presentation usually involves weight loss, diarrhea, fatigue and anemia.

Has numerous extra-intestinal manifestations affecting the skin, bones, joints, brain, heart and other organs.

Long term complications include osteoporosis, increased fracture risk, infertility and increased risk of small bowel malignancy.

Population-based studies have shown that celiac disease poses up to a 30% increased risk of cancer, with the most common malignant diagnoses being lymphoma and GI cancers, including esophageal, hepatocellular, and colorectal.

Celiac disease presents the strongest associations to gastrointestinal and lymphoproliferative cancers.

In celiac disease, the autoimmune reaction is caused by the body’s loss of immune tolerance to ingested gluten, found primarily in wheat, barley, and rye.

increased risk of gastrointestinal cancers, as the gastrointestinal tract includes the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, rectum, and anus, all areas that the ingested gluten would traverse in digestion.

Associated with a decreased risk of breast and lung cancer.

Patients with celiac disease have between a 35% and 39% increased all-cause mortality risk.

Increased risk for cancer is within the first 15 years after diagnosis.

Almost half the patients have evidence of osteoporosis.

Prevalence of biopsy proven celiac disease in patients with criteria for irritable bowel syndrome is about 4%.

Increased incidence of T cell lymphomas and adenocarcinomas, and early diagnosis and treatment of the disease may reduce the risk of malignancy.

Prevalence of biopsy confirmed celiac disease in diabetics is 7% but most such patients are asymptomatic.

Increasing incidence in childhood and adults.

Infants and children typically present with symptoms of malabsorption, including diarrhea and failure to thrive.

Non gastrointestinal presentations may include anemia, thyroid dysfunction, osteoporosis, liver function test abnormalities and skin manifestations such as dermatitis herpetiformis.

Patients with untreated CD commonly have abnormal liver function tests, as a result of a reactive hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

In a group of patients with CD who underwent liver biopsy, more than half were found to have an autoimmune cause of liver disease, with autoimmune hepatitis being the most common.

Celiac disease is present in 2.2 to 7.9% of patients who have fatty liver and a normal BMI.

There is an increased risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among patients with celiac disease.

Can be diagnosed at any age and can affect many organ systems.

Diagnostic delay averages 11 years from the onset of symptoms diagnosis.

Undiagnosed disease can lead to osteoporotic fractures, infertility, unnecessary surgical procedures including bowel resection and malignancy.

In recent diagnosed cases classic clinical features of diarrhea and weight loss are being seen less commonly.

Classic CD described patients with CD who present with features of a malabsorption syndrome; a combination of diarrhea, steatorrhea, weight loss, or growth failure.

Nonclassic CD clinical manifestations are characterized by a predominance of extraintestinal features: often iron deficiency anemia, premature metabolic bone disease, infertility, elevated transaminase levels in the absence of clinical malabsorption.

Fracture risk related to metabolic bone disease may be 2 to 3 times higher in patients with CD than in the general population.

CD should be considered in patients with premature metabolic bone disease.

All patients with newly diagnosed CD should undergo an assessment of bone health.

Adult patients with newly diagnosed CD should undergo bone densitometry either at the time of diagnosis or 1 year after starting treatment because the frequency of osteoporosis may be as high as 34% in patients with malabsorption.

Other associated features of CD include functional asplenia, enteropathy-associated arthropathy, seizures, peripheral neuropathy, ataxia, infertility, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, dental enamel defects, headaches, and brain fog.

Potential CD refers to patients with normal small intestinal mucosa who are at increased risk for development of the disease as indicated by positive CD serologic findings.

On removal of gluten from diet symptoms and abnormal intestinal mucosal changes resolve.

Symptom relief is typically quite fast in patients with CD once a gluten-free diet has been commenced.

The mean time to symptom improvement is 4 weeks with a gluten-free diet.

Two -thirds of patients have complete relief at 6 months with a gluten-free diet.

When a gluten-free diet is started, there is a rapid decline in serologic titers by 6 months.

3 to 6 months after the initial diagnosis should be allowed for CD assessment of clinical response to the gluten-free diet and to recheck serologic titers.

Adult patients should undergo upper endoscopy with small bowel biopsies in follow-up to prove there has been histologic healing in view of the excess comorbidity in patients without healing.

Nonresponsive CD is characterized by: persistent or recurrent symptoms after starting a gluten-free diet.

Symptoms are diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, fatigue, and bloating.

In the presence of ongoing diarrhea and negative serologic results, colonoscopy with random biopsies should also be considered to rule out microscopic colitis given the strong association between microscopic colitis and CD.

Other in patients with persistent symptoms include irritable bowel syndrome, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, pancreatic insufficiency, lactose or fructose intolerance, inflammatory bowel disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and peptic ulcer disease

Up to 30% of patients have a poor response to gluten free diet.

The most common reason for nonresponsive CD is gluten contamination: either blatant or inadvertent.

Most frequent reason for inadvertent gluten consumption: cross-contamination in packaged foods, at restaurants, medications or supplements, overlooked sources of gluten include beer and other alcohol, sauces, lipstick or lip balm.

Persistently positive serologic results after 12 months of a gluten-free diet strongly supports gluten contamination.

Upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsies is often recommended to clarify the etiology of persistent symptom.

Less compliant CD patients include: those who were asymptomatic or had nonclassic features at presentation, teenagers, those who are diagnosed later in life, frequent travelers or socialites, and those with any change in social situation.

It increases the risk of intrauterine growth restriction by an odds ratio of approximately 2.48.

Both seologic and histologic changes normalize with a gluten free diet.

Dietary nonadherence major cause of recurrent or persistent symptoms.

Refractory celiac disease refers to persistence or recurrent malabsorption symptoms and signs with villous atrophy on biopsy despite a strict gluten-free diet for more than 12 months.

Refractory celiac disease is classified as type I or type 2.

Refractory celiac disease type I is referred to as normal intraepithelial lymphocyte disease.

Refractory celiac disease type 2 is referred to as abnormal intraepithelial lymphocytic disease: clonal intraepithelial lymphocytes lacking surface markers CD3, CD8, and T cell receptors or both.

Type 2 is associated with a higher risk of also jejunoileitis and lymphomas.

Refractory CD (RCD) is characterized by persistent or recurrent symptoms and enteropathy despite strict adherence to a gluten-free diet for at least 12 months after exclusion of other causes of nonresponsive CD and malignancy.

Two types of refractory CD exist:

type 1, with normal intraepithelial lymphocyte morphology, and type 2, with aberrant intraepithelial lymphocytes and T-cell receptor clonality.

Survival is reduced in patients with both types of refractory CD, but worse in patients with type 2-5-year survival, 80% vs 50%, respectively.

The presence of a low serum albumin concentration is an independent risk factor for mortality in refractory CD.

Refractory CD type 1 responds well to corticosteroid therapy alone, or in combination with azathioprine.

No consensus exists on the best treatment for RCD: corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, cyclosporine, alemtuzumab, cladribine, or autologous stem cell transplant.

Natural history of the disease process varies greatly among patients: The sequence of events are such that there is the appearance of celiac antibodies, followed by the development of an intestinal enteropathy, followed by symptom onset, and then development of complications.

In the above scenario patients may not experience all these events, and the duration of each phase may range from weeks to decades.

In some patients loss of gluten tolerance to be reversible.

Diagnosis by biopsy of the small intestine is required in most patients.

Diagnosis is associated with histological changes including an increased number of intraepithelial lymphocytes, greater than 25 per 100 enterocytes, elongation of the crypts, and partial to total villous atrophy.

False positive results may occur in improperly prepared specimens, and false-negative results may occur due to the patchiness of mucosal damage involvement.

Subepithelial anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody IgA deposits demonstrated by double immunofluorescence technique may aid in the diagnosis.

In children, a biopsy of the small intestine may not be necessary in patients with typical symptomatology and a high titerb of anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies, more than 10 times the upper limit of normal and predisposing HLA genotypes.

Refractory celiac disease is defined by the persistence or recurrence of malabsorption syndrome and intestinal villous atrophy despite a strict gluten-free diet for more than 12 months.

Refractory celiac disease hallmark is an accumulation of an aberrant intraepithelial lymphocytes.

The amount of aberrant intraepithelial lymphocytes differentiates between type I and type II refractory celiac disease.

Type II refractory celiac disease has a poor prognosis because of severe malnutrition, the presence of frequent infections, and a high risk for the development of lymphoma, leading to a five-year survival rate of less than 50%.