The burden of aging includes an array of health, social, and economic challenges.

The burden of aging includes an array of health, social, and economic challenges.

Aging populations experience a higher prevalence of chronic diseases, functional disabilities, and multimorbidity, which significantly impact their quality of life and healthcare needs.

Many chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, malignant neoplasms, chronic respiratory diseases, musculoskeletal diseases, and neurological disorders are leading contributors to the disease burden in older adults.

The prevalence of multiple chronic conditions increases with age, leading to greater healthcare utilization and costs, functional disabilities, including impairments in activities of daily living (ADLs), reduced independence and increasing the need for long-term care.

Aging has profound increased healthcare expenditures, driven by the higher prevalence of chronic diseases and the need for long-term care, straining healthcare systems and social services.

The economic burden of aging extends to families and caregivers, who often bear the physical, emotional, and financial costs of providing care.

As the proportion of older adults rises, there is a growing need for age-appropriate healthcare services, policies, and interventions to prevent and manage chronic diseases and disabilities.

Compression of morbidity that improves health is more valuable than further increases in life expectancy.

Targeting aging offers potentially larger economic gains than eradicating individual diseases.

A slowdown in aging that increases life expectancy by 1 year is worth US$38 trillion, and by 10 years, US$367 trillion.

Ultimately, the more progress that is made in improving how we age, the greater the value of further improvements.

Life expectancy (LE) has increased dramatically over the past 150 years, although not all of the years gained are healthy.

The Global Burden of Disease data suggests that the proportion of life in good health has remained broadly con- stant, implying increasing years in poor health.

The disease burden is shifting towards chronic non-communicable dis- eases, estimated to cause 70%of deaths in the United States.

A substantial part of life, and certainly most deaths, occur in a period in the lifespan when the risk for frailty and disability increases exponentially.

There is a growing emphasis on healthy aging and an emerging body of research focusing on the biology of aging.

Questions: is it preferable to make lives healthier by compressing morbidity, or longer by extending life?

What are the gains from targeting aging itself, with its potential to make lives both healthier and longer?

Interactions between health, longevity, economic decisions and demographics create a virtuous circle: the more successful society is in improving how we age, the greater the economic value of further improvements.

Changes in health or longevity lead to changes in economic decisions.

As health improves in later life, individuals respond by allocating more consumption and leisure to these years, and gains in health at older ages become more attractive.

It is assumed that aging occurs through the accumulation of biological damage, and that slowing aging lessens the pace at which health and mortality deteriorate with age.

Delaying aging leads to a virtuous circle in which slowing aging begets demand for further slowing in aging.

This virtuous circle arises because society’s gains from delaying aging rise with the average age of society, increase with the qual- ity of life in old age, and depend on the number of older people.

There is a distinctive dynamic to targeting aging compared to treatments aimed at specific diseases, in which gains diminish once successful treatments are discovered.

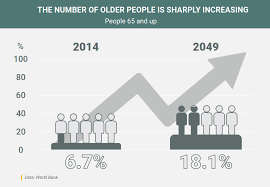

In 2050, 80% of older people will be living in low- and middle-income countries.

The pace of population ageing is much faster than in the past.

In 2020, the number of people aged 60 years and older outnumbered children younger than 5 years.

Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world’s population over 60 years will nearly double from 12% to 22%.

Today most people can expect to live into their sixties and beyond.

The pace of population ageing is much faster than in the past.

By 2030, 1 in 6 people in the world will be aged 60 years or over.

At this time the share of the population aged 60 years and over will increase from 1 billion in 2020 to 1.4 billion.

By 2050, the world’s population of people aged 60 years and older will double (2.1 billion).

The number of persons aged 80 years or older is expected to triple between 2020 and 2050 to reach 426 million.

Population ageing started in high-income countries and it is now low- and middle-income countries that are experiencing the greatest change.

By 2050, two-thirds of the world’s population over 60 years will live in low- and middle-income countries.

Aging results from the impact of the accumulation of a wide variety of molecular and cellular damage over time.

Aging leads to a gradual decrease in physical and mental capacity, a growing risk of disease and ultimately death.

These changes are neither linear nor consistent, and they are only loosely associated with a person’s age in years.

Beyond biological changes, aging is often associated with other life transitions such as retirement, relocation to more appropriate housing and the death of friends and partners.

Common conditions in older age include hearing loss, cataracts and refractive errors, back and neck pain and osteoarthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, depression and dementia.

With aging people are more likely to experience several conditions at the same time.

Older age is also characterized by the emergence of several complex health states commonly called geriatric syndromes: including frailty, urinary incontinence, falls, delirium and pressure ulcers.

Longer life brings opportunities to older people and their families, but also for societies.

Additional years provide opportunity to pursue further education, a new career or a passion.

All of these opportunities and contributions depend heavily on one factor: health.

Evidence suggests that the proportion of life in good health has remained broadly constant, implying that the additional years are in poor health.

If people with advancing age experience these extra years of life in good health their ability to do the things they value will be little different from that of a younger person.

However, If these added years are dominated by declines in physical and mental capacity, the implications for older people and for society are more negative.

The variations in the health of the elderly are due to genetics, but mostly to people’s physical and social environments – including their homes, neighbourhoods, and communities, as well as their personal characteristics – such as their sex, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status.

The environments that people live in as fetuses and children combined with their personal characteristics, have long-term effects on how they age.

The physical and social environment can affect health directly or through barriers or incentives that affect one,s decisions and health behaviour.

Maintaining healthy behaviours throughout life, eating a balanced diet, engaging in regular physical activity and refraining from tobacco, alcohol or drug abuse, all contribute to reducing the risk of non-communicable diseases, improving physical and mental capacity and delaying care dependency.

Supportive physical and social environments also enable people to participate in matters important to them, despite losses in capacity.

The availability of safe facilities and transport, and places with supportive environments create a public-health response to aging

Providing individual and environmental approaches that ameliorate the losses associated with older age are necessary but also those efforts that may reinforce recovery, adaptation and psychosocial growth.

There is no typical older person, as some 80-year-olds have physical and mental capacities similar to many 30-year-olds, and others experience significant declines in capacities at much younger ages.

The diversity seen in older age is not random.

A large part arises from people’s physical and social environments and the impact of these environments on their opportunities and health behavior.

The relationship we have with our environments is skewed by personal characteristics such as the family we were born into, our sex and our ethnicity, leading to inequalities in health.

Older people are often assumed to be frail or dependent and a burden to society.

Globalization, technological developments, urbanization, migration and changing gender norms are influencing the lives of older people in direct and indirect ways.

The population is aging at an unprecedented rate, with the baby boomer generation, defined as those born between 1946 and 1964, reaching retirement age and living longer than ever before.

By 2030, all baby boomers will be older than 65, leading to about one in every five residents being retirement age.

The implications of this demographic shift are far-reaching.

It is necessary to address the social determinants of health, such as income, education, housing, transportation, and social support, that impact the health outcomes and health behaviors of the older adults.

There is a growing shortage of healthcare providers, the supply and availability of qualified and skilled healthcare professionals, such as physicians, nurses, pharmacists, clinical social workers and technicians, is insufficient and inadequate to meet the demand and need of the population.

This phenomenon is even more pronounced in low- and middle-income countries, as well as in the rural and remote areas within the U.S.

The global health workforce is projected to grow to 53.9 million by 2030, but still falls short of the estimated demand of 80 million by 2030, resulting in a global shortfall of 18 million health workers, mostly in low- and middle-income countries.

In the U.S. it is predicted a shortage of up to 139,000 physicians by 2038.

The U.S. population is aging rapidly because of two interrelated factors: the aging of the baby boomer generation, and the increase in life expectancy.

The baby boomer generation constitutes the largest cohort in the U.S. history, with about 73 million members.

The population that is 65 and older will increase significantly, from 17% in 2022 to 21% in 2030, and to 23% in 2050.

By 2050, the number of Americans aged 65 and older will increase by 40%, from 58 million in 2022 to 82 million in 2050.

The elderly adults often suffer from multiple and complex health conditions, including age-related diseases that affect their heart, brain, and immune system, and medical system lacks the experience and expertise to effectively treat these diseases and provide specialized, personalized care for this vulnerable group.

The increase in the share and size of the older population will have implications for the demand and supply of healthcare and social services, as well as for the economic and fiscal stability of the nation.

One of the main drivers of the increased healthcare demand and utilization among the elderly is the high prevalence of multiple chronic conditions (MCCs), which are defined as having two or more chronic diseases that last at least a year and require ongoing medical attention or limit activities of daily living.

According to the CDC, 88% of older adults have at least one medical chronic conditions, and 60% have at least two: hypertension, arthritis, heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease.

Multiple medical chronic conditions are associated with increased mortality, disability, functional decline, and reduced quality of life, and pose significant challenges to healthcare provision and management, as they require complex and coordinated care across multiple settings and providers.

Those with MCCs accounted for 94% of total healthcare expenditure compared to 6% for those without MCCs

The high prevalence of MCCs among the elderly is expected to persist or even increase in the future, as it is closely linked to the increase in life expectancy.

As people live longer, they are more likely to develop and accumulate chronic diseases over time, especially if they have risk factors such as age-related physiological changes, environmental exposures, lifestyle behaviors, genetic predispositions, and social determinants of health.

Te increase in life expectancy in the U.S. between 1998 and 2008 was accompanied by an increase in the number of years spent with MCCs, especially among the elderly.

The study estimated that the average number of years spent with MCCs increased from 7.2 to 8.6 for men aged 65 and older, and from 10.0 to 11.3 for women aged 65 and older.

The aging population will face a higher burden of chronic diseases and a lower quality of life in the coming decades.

Making matters worse, the health and longevity of

The next wave of aging people may also be affected by new external triggers, such as obesity, processed food intake, microbiome changes, climate change, pandemics, and pollution, which can have diverse and unpredictable impacts on different individuals.

These triggers can also change the health behaviors and healthcare access of the elderly.

The medication requirements of the aging population is polypharmacy, which is defined as the concurrent use of five or more medications18. Individuals aged 65 and over account for over a third of all prescribed medications in the U.S.

Polypharmacy has increased risk of drug interactions, adverse drug events, medication non-adherence, and medication errors, which can lead to poor outcomes, such as reduced effectiveness, increased morbidity and mortality, and decreased quality of life.

Therefore, polypharmacy necessitates careful medication management and monitoring, as well as regular medication reviews and deprescribing when appropriate.

Polypharmacy was associated with higher rates of emergency department visits and hospitalizations.

Federal spending on major health programs for the elderly, such as Medicare and Medicaid, will increase from 6.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020 to 9.2% of GDP in 2050.

The rising amount of healthcare needs due to an aging population is multifaceted, encompassing increased service utilization, higher prevalence of chronic diseases, escalated healthcare spending, and complex medication management, and unprecedented demands on the healthcare system.

Innovative approaches in care delivery, financial planning, and resource allocation requires a concerted effort from healthcare providers, policymakers, and stakeholders to ensure that the system is not only responsive but also sustainable in meeting the evolving needs of an aging society.

The demand for healthcare workers is expected to outpace the supply.

The healthcare workforce shortage is driven by several factors, such as the aging of the workforce itself, the insufficient supply of new entrants, the uneven distribution across regions and specialties, and the increased workload and stress of the workers.

The shortage of healthcare providers will affect the entire healthcare system, affecting the quality, accessibility, and affordability of care.

Physician shortages lead to increased mortality, reduced preventive care, and higher healthcare spending.

The shortage of physicians creates a competitive environment that may result in sector consolidation, where larger and more affluent providers acquire or merge with smaller and less profitable ones, creating economies of scale and scope.

This consolidation may also have negative consequences, such as reduced competition, increased market power, and higher prices.

The current system is not well prepared to handle the increase in volume and complexity of care, resulting in overcrowding, wait times, delays, cancellations, and rationing of care.

The medical system wastes about $750 billion, or 30% of its spending, every year on unnecessary or excessive costs, fraud, and other inefficiencies

The medical system has high variation in the quality and results of care across different providers, places, and regions, which can lead to too much, too little, or improper use of services

Medicare spending per beneficiary ranges by more than three times across regions, and that more spending did not mean better quality or satisfaction.

The U.S. has seen a decline in the number of hospital beds per person reflecting the move from inpatient to outpatient care and the attempts to save costs and enhance efficiency.

This that there is less excess capacity to cope with fluctuations in demand, such as during pandemics, disasters, or seasonal variations.

The U.S. healthcare system is lagging behind in the adoption and use of information and communication technology: electronic health records (EHRs), telemedicine which can improve the quality, safety, and coordination of care, as well as reduce the costs and errors of care.

The resource gap in the U.S. healthcare system will have serious consequences for the health and well-being of the elderly, who are more vulnerable and dependent on the availability and quality of care.

The U.S. ranked last among 11 high-income countries in the health outcomes and experiences of older adults, with the highest rates of mortality, disability, hospitalizations, and unmet needs (Commonwealth Fund).

The U.S. healthcare system is unable to meet the rising and complex needs of the aging population.

This crisis requires a strategic and comprehensive approach that involves increasing the quantity and quality of the healthcare workforce, enhancing the availability and accessibility of the healthcare resources, and improving the performance and productivity of the healthcare delivery.

As the need for healthcare services increases due to the aging population, and the supply of healthcare workers and resources remains insufficient and inadequate, a new form of fragmentation and disparity is emerging in the U.S. healthcare system: the rich-poor divide.

This phenomenon is where the affluent and urban areas attract and retain more and better healthcare professionals and facilities, while the poor and rural areas are left with fewer and worse healthcare options:leading to further widening of the health and economic gaps between them.

As the number of individuals living into their 80s, 90s and beyond increases dramatically, focus has shifted from extending lifespan to enhancing the quality of these additional years.

Delayed aging increases the number of years lived without the accumulation of chronic conditions and other side effects of aging.

Achieving this would result in the compression of morbidity, meaning that chronic illnesses would be concentrated into a shorter period towards the end of life.

This shift would not only have an impact on the general health of the population, would also have a positive financial impact.

Geroscience is central to increasing the number of healthy years in older populations.

A key strategy involves identifying biomarkers and risk factors, such as socioeconomic and lifestyle choices, that predict disease development in later life.

Identifying risk factors of aging: issues such as immune aging, chronic low-grade tissue inflammation, obesity, mitochondrial age-related insufficiency, and brain proteinopathies.

The advent of the GLP-1 drug class have the potential to prevent obesity-related diseases later in life, also offers a promising avenue for the reversal of metabolic aging and may even promote DNA repair in neurodegenerative diseases.

Maintaining muscle function is important in the context of aging or chronic conditions like sarcopenia.

Muscle augmenting factors and the ability to mobilize and differentiate muscle stem cells promote healthy aging.

There is evidence that compression of morbidity may be due more to socioeconomic factors than biological determinants.