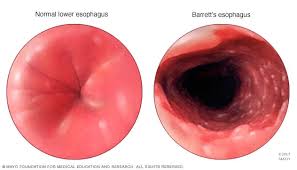

Condition in which the normal squamous epithelium of the distal esophagus is replaced by a metaplastic intestinal epithelium as a consequence of longstanding gastrointestinal reflux disease:columnar metaplasia.

Barrett’s esophagus results from reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus with inflammation and chronic tissue injury.

Phases: initiation phase-manifested by a genetic predisposition, exposure to reflux and transformation of cell phenotype: formation phase-characterized by phenotype changing to Barrett’s esophagus: and progression phase-manifested by dysplasia and cancer formation.

Stages of Barrett’s esophagus: non-dysplastic, low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and invasive adenocarcinoma.

Metaplastic and dysplastic changes contain varying levels of genetic changes, and as the number of genetic changes increase phenotypic changes occur progressing towards malignancy.

Genetic changes of tumor suppressor genes p53 and p16, tetraploidy, aneuploidy and CpG island methylation proposed as risk predictors for progression to cancer associated they are markers for genomic instability.

With an estimated progression rate for nondisplastic Barrett’s esophagus of 0 to 3% per year, most patients will not progress.

Patients with Barrett’s esophagus have approximately a 3-5% risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma in their lifetime.

A metaanalysis of 24 studies found that patients initially diagnosed with Barrett esophagus without dysplasia had a 0.2% to 0.5% annual rate of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma; for patients with Barrett’s esophagus and low grade dysplasia, the annual incidence rate of esophageal carcinoma was 0.54% in the annual incidence of either esophageal adenocarcinoma or high-grade dysplasia was 1.73%.

Familial Barrett’s esophagus accounts for approximately 7% of all cases of Barret’s esophagus and esophageal cancer cases.

The squamocolumnar junction and the gastroesophageal junction are located same level in healthy individuals, however, in Barrett’s esophagus this junction is displaced proximally.

Prevalence in the US is not known, but in a population-based study in Sweden it was noted to be present in 1.6% of 3000 study participants (Ronkainen J).

Barrett’s esophagus affects approximately 5% of people in the United States, and approximately 1% worldwide.

Most cases remain undiagnosed.

Compared with controls, patients with Barrett esophagus were 8 to 16 times more likely to report severe or very severe GERD symptoms.

No randomized clinical trial exists to support screening in clinical practice to identify patients with Barrett esophagus.

Progression of Barrett’s esophagus may involve the progression of low-grade dysplasia and high-grade dysplasia before the development of malignancy.

The prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in patients with chronic GERD is 5.6% in one endoscopic screening study (Rex DK).

There is significant inter-observer variability in the clinical recognition of Barrett esophagus, and there is significant variability in the histopathological diagnosis as well.

An endoscopy with a longer time than one minute per centimeter is associated with the detection of more endoscopic suspicious lesions.

High quality endoscopy consisting of high definition endoscopes, clearing of the esophageal mucosa, and spending sufficient inspection time are important in the diagnosis of neoplasia in Barrett esophagus patients

An estimated 3% to 6% of individuals with gastric reflux have Barrett’s esophagus, the precursor lesion to esophageal adenocarcinoma, but only about 20% of these are diagnosed.

Elevated intra-abdominal pressures in centrally obese patients may increase gastroesophageal reflux through mechanical disruption of the GE junction leading to esophageal injury and development of Barrett’s esophagus.

The metabolic syndrome is associated with Barrett’s esophagus.

Patients with metabolic syndrome have a nearly twofold increased risk of BE.

The metabolic syndrome associated with Barrett’s esophagus is independent of reflux symptoms, may reflect a reflex independent pathway of Barrett’s esophagus pathogenesis (Leggett CL et al).

BE associated with esophageal inflammation, dysphasia and visceral fat, suggesting other associations than reflux for pathogenesis.

An inverse association between Barrett’s esophagus and consumption of red wine, Helicobacter pylori infection and black race exist.

The benefit of screening with endoscopy is controversial as almost half the patients in whom esophageal adenocarcinoma develops have no previous symptoms of heartburn.

The risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with heartburn is less than one case per thousand person-years.

This lesion may occur in the absence of symptoms of reflux.

Symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux are not accurate predictors of the risk of developing BE or esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Only recognized pathologic precursor esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Most patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma do not have a previous diagnosis of BE.

Only 5% of patients undergoing surveillance for BE develop esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Annual risk for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma is less than 1%.

Barrett esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma is most prevalent in white males.

It is more common in men than women.

Pathological evaluation of neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus:

Negative for dysplasia

Indefinite for dysplasia-glandular and nuclear changes equivocal

Low-grade dysplasia on enlarged nuclei with increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, mucin depletion and lack of surface maturation

High-grade dysplasia-nuclear changes more pronounced than in low-grade dysplasia, marked nuclear pleomorphism, architectural complexity and loss of polarity-equivalent to carcinoma in situ

Intramucosal carcinoma-neoplastic cells invading beyond the basement membrane into the lamina propria or muscularis mucosa-equivalent to T1a stage

Invasive adenocarcinoma-neoplastic cells invading through muscularis mucosa into the submucosa were deeper layers of the esophagus-T1b defined as invasion the submucosa and T2 defined as invasion of muscularis propria.

Annual risk of esophageal cancer 0.2%-2.

No clinical trials have demonstrated that screening for Barrett esophagus reduces death rates from eosphageal carcinoma.

In a study of 11,028 patients with BE followed for a median of 5.2 years, was associated with an annual risk of 0.12% for esophageal carcinoma (Hvid-Jensen, F et al).

The risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma is 30 to 40 times higher among patients with Barrett’s esophagus as among individuals without this condition.

Patients have a 5-10% lifetime risk of progression to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.

No treatment has been shown to decrease the risk of esophageal cancer.

Higher rates of progression from Barrett esophagus to esophageal adenocarcinoma includes older age patients, male sex, history of smoking, and low grade dysplasia, longer length of Barrett esophagus.

Barrett’s esophagus length, age, sex, race, mean body mass index, family history of esophageal cancer, proton pump inhibitor use, and total duration of follow-up as risk markers,only the Barrett’s disease length was a significant predictor of progression to esophageal cancer.

Surveillance high quality video endoscopy is suggested for metaplastic lesions with targeted biopsy specimens, with a four quadrant biopsy protocol and specimens taken every 2 cm along the extent of the Barrett’s esophagus-can increase the yield of low-grade dysplasia by 17% and high grade dysplasia by 3% compared to random biopsy specimens (Abelav JE et al).

During endoscopic surveillance random biopsies sample only 4-6% of the surface area of the metaplastic epithelium, and dysplastic and malignant lesions within the Barrett’s segment have focal or patchy involvement.

Surveillance for patients without dysplasia in whom two endoscopic examinations a year apart have shown no evidence of disease progression, surveillance interval can be extended up to three years.

Surveillance for patients with low-grade dysplasia annual surveillance is recommended, yet no program of surveillance has had any effect on survival.

Longer segments of Barrett’s esophagus are evaluated with endoscopy every three years, while shortly segments of Barrett esophagus of less than 3 cm are evaluated with endoscopy every five years.

Surgical removal of such lesions not done because of high morbidity and mortality rate of esophagectomy.

Acid and bile salts together are synergistic in the development of Barrett’s esophagus.

Up to 50% of patients with high-grade dysplasia may have endoscopically undetectable cancer.

Barrett’s esophagus is diagnosed in approximately 10 to 15% of patients with reflux disease that undergo endoscopy.

Endoscopic screening in patients without chronic reflux symptoms indicate the prevalence Barrett’s esophagus in 5.6% of patients (Rex DK).

A complication of excessive reflux of gastric juice which transfers the normal squamous epithelium of the distal esophagus into columnar epithelial cells containing goblet cells.

Estimated that 2.5 million Americans have Barrett’s esophagus.

Rarely undergoes regression.

Primary cause is GERD.

Up to 3-5% of patients with chronic GERD have short segment Barrett’s and 10-15% have long segment Barrett’s esophagus.

Short segment disease refers to involvement of 3 cm or less and long segment involvement refers to esophageal involvement of Barrett’s of greater than 3 cm.

Extent of involvement graded also by the Prague circumference and maximum criteria based on the circumferential and maximal extent of the columnar lined esophagus (Sharma P).

Patients frequently have a hiatus hernia and weakened gastroesophageal sphincter.

Associated with white race, increasing age, obesity and increased severity and duration of GERD.

Occurs in 15-20% of patients with GERD.

In one study from Sweden only 56% of patients with Barrett’s esophagus complained of reflux symptoms, the incidence of Barrett’s was 1.6% of the population.

Autopsy data suggests a higher frequency of largely undetected Barrett’s esophagus in the asymptomatic population.

An inverse association between the presence of this entity and consumption of red wine, Helicobacter pylori infection and black race have been noted.

A precursor of adenocarcinoma.

Genetic changes that occur include loss of CDKN2A (p16), p53 and the development of aneuploidy and tetraploidy.

Estimated to take decades to progress to adenocarcinoma.

Environmental factors that contribute changes of Barrett’s to adenocarcinoma include cigarette smoking, obesity and increased body mass index.

Risk for adenocarcinoma is 30 to 125 times the general population.

Estimated 0.5% annual rate of transformation to a malignant state (Sharma P et al).

The presence of Barrett’s increases the risk of cancer over time.

Cancer risk highly variable ranging from negligible to approximately 30% for high grade dysplastic changes.

Acid control has not led to regression of metaplastic mucosa.

Antirelux interventions or aimed at controlling symptoms of reflux and promote healing of the esophageal mucosa, but such management does not reduce the risk of esophageal cancer.

Indications are for anti-reflux surgery are the same as for chronic reflux, that is a lack of response to or inability to tolerate proton pump inhibitors, and not the presence of Barrett’s esophagus.

Antireflux surgery is superior to medical therapy in the prevention of Barrett’s metaplasia.

Patients with GERD who have poor esophageal peristalsis and severely impaired function of the lower esophageal sphincter should undergo antireflux surgery even in the presence of mild esophagitis.

No study has shown any increase in longevity from Barrett’s esophagus because of surveillance.

Endoscopic surveillance is recommended standard of care for early detection of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.

Endoscopic surveillance in case control and code words studies have demonstrated an earlier stage of esophageal adenocarcinoma at diagnosis and improved survival(Cooper GS).

Because of lead time bias, in it is felt that it remains problematic, to conclude that surveillance studies prolong life even though a population-based cohort study indicated that 11 of 23 patients with cancer detected by in this endoscopic surveillance trial were alive at two years, as compared with none of the patients presenting clinically (Corley DA).

Benefits from surveillance with endoscopy is limited by the low overall incidence of cancer in patients with Barrett’s esophagus, the absence of a previous diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus in the majority of patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, difficulties with diagnosis of dysplasia.

Barrett esophagus evaluation is typically performed with conventional white light high definition upper endoscopy.

Newer modalities for evaluating for Barrett esophagus includes swallowed cell collection devices, transnasal endoscopy, and esophageal capsule endoscopy that do not require sedation.

Unsedated transnasal endoscopy is an alternative to conventional upper endoscopy with comparable performance to conventional upper endoscopy for screening.

Unsedated transnasal endoscopy has a sensitivity of 98% of the specificity of 100% compared with conventional endoscopy for diagnosing Barrett esophagus and is associated with lowered costs and fewer adverse events because of the absence of sedation.

With low grade dysplasia the incidence for esophageal adenocarcinoma range is from 0.6%-1.6% per year, and the lower range is similar to the incidents in patients with Barrett’s esophagus who do not have dysplasia.

In patients with nondysplastic epithelium the risk of esophageal cancer is 1 per 3 patient-years.

With high-grade dysplasia there is an estimated development of esophageal adenocarcinoma of 6.6 cases per hundred patient years.

Recent studies suggest that the cancer risk has been overestimated and that life expectancy does not differ significantly with other benign esophageal disorders or from the general population.

Unsedated transnasal endoscopy and esophageal video capsule endoscopy may be alternatives to sedated endoscopy for BE screening.

First line therapy consists of proton pump inhibitors to control reflux symptoms, but their role in chemo prevention is unclear.

Acid exposure elimination with PPIs to prevent progression of Barrett esophagus to esophageal carcinoma is recommended.

Endoscopic therapy has reduced the need for surgical intervention for patients with early esophageal adenocarcinoma and high-grade disease.

Visible neoplastic lesions in patients with Barrett esophagus can be resected using endoscopic techniques and endoscopic ablative therapy may be used to eradicate any residual flat Barrett esophagus segments.

In a multicenter randomized clinical trial with a confirmed diagnosis of BE with low grade dysplasia randomized to radiofrequency ablation or endoscopic surveillance: radiofrequency ablation resulted in a reduced risk of neoplastic progression over 3 years (Phoa KN et al).

In the above study RFA reduced the risk of progression to high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma by 25%.

In the above study RFA completely eradicated dysplasia and intestinal metaplasia, but it persisted in a majority of patients.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) provides the most efficient modality, since it has been demonstrated to successfully eradicate BE with or without dysplasia with acceptable safety, efficacy and durability profiles.

In conjunction with proton pump therapy, this new technology has become the standard care for patients with dysplastic BE.

In a phase III randomized ASPECT multicenter study there was 25% risk reduction for esophageal adenocarcinoma associated with long-term chemoprevention regimen of daily high doses of proton pump inhibitor plus aspirin.

The use of the Cytospnge increases detection of Barrett’s esophagus by multiple times over the current standard of care.

Lesions with neoplasia in patients with Barret esophagus can be resected using endoscopic mucosal resection, and with small lesions located no deeper than the superficial submucosal layer are resected or submucosal section, in which larger lesions within the deep submucosa are resected with overall rates of remission at three months greater than 93%.

Resection of visible neoplastic bearing lesions is followed by ablation consisting of application of hot or cold to the esophageal mucosal to eradicate metaplasia.

Ablation of flat Barrett esophagus can be performed without resection.

Radio frequency ablation is the most established method for patients with confirmed high-grade dysplasia.

In a pooled analysis study showed that 73% of patients undergoing endoscopic mucosal resection with subsequent radio frequency ablation had complete eradication of metaplasia, strictures occurred in 10% of patients, bleeding in 1.1% of patients and perforations in 0.2% of patients.

Recurrence of esophageal adenocarcinoma occurred in 1.4% of patients, dysplasia in 2.6% and intestinal metaplasia occurred in 16.1% in a follow up ranging from 12 to 67 months.

Endoscopic mucosal resection is necessary for visible lesions to achieve complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia.

Guidelines recommend endoscopic therapy for patients with high-grade dysplasia and early esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Endoscopic therapy is considered in patients with low-grade dysplasia, but is not recommended for patients with non-dysplastic Barret’s esophagus.