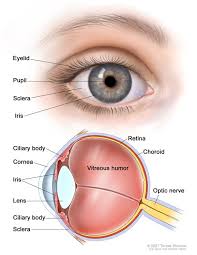

The iris is a thin, annular structure in the eye responsible for controlling the diameter and size of the pupil, and thus the amount of light reaching the retina.

The pupil is the eye’s aperture, while the iris is the diaphragm.

Eye color is defined by the iris.

The iris in humans is colored as typically brown, blue, or green, an area, with the pupil in its center, and surrounded by the white sclera.

Precursor from mesoderm and neural ectoderm

Long posterior ciliary arteries

Long ciliary nerves, short ciliary nerves

The iris consists of two layers

The front layer is a pigmented fibrovascular layer known as a stroma.

Behind the stroma, are pigmented epithelial cells.

The stroma is connected to a sphincter muscle, the sphincter pupillae, which contracts the pupil in a circular motion, and a set of dilator muscles (dilator pupillae), which pull the iris radially to enlarge the pupil, pulling it in folds.

The iris colored portion of the eye controls the size of the pupil by contracting the sphincter pupillae and dilator pupillae muscles.

The sphincter pupillae is the opposing muscle of the dilator pupillae.

The pupil’s diameter, and inner border of the iris, changes size when constricting or dilating, but the outer border of the iris does not change size.

The constricting muscle is located on the inner border of the iris.

The iris’s back surface is covered by a heavily pigmented epithelial layer that is two cells thick, and the front surface has no epithelium.

This anterior surface acts as the dilator muscles.

The high pigment content of the iris blocks light from passing through the iris to the retina, restricting it to the pupil.

The outer edge of the iris, (root) is attached to the sclera and the anterior ciliary body.

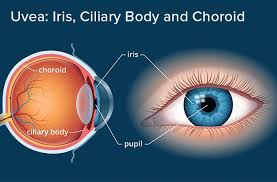

The iris and ciliary body together are known as the anterior uvea.

Just in front of the root of the iris is the trabecular meshwork, through which the aqueous humour constantly drains out of the eye, with the result that diseases of the iris often have important effects on intraocular pressure and indirectly on vision.

The iris along with the anterior ciliary body provide a secondary pathway for aqueous humour to drain from the eye.

The iris is divided into two major regions:The collarette is the thickest region of the iris, separating the pupillary portion from the ciliary portion.

The pupillary zone is the inner region whose edge forms the boundary of the pupil.

The ciliary zone is the rest of the iris that extends to its origin at the ciliary body.

The collarette is defined as the region where the sphincter muscle and dilator muscle overlap.

Radial ridges extend from the periphery to the pupillary zone, to supply the iris with blood vessels.

The root of the iris is the thinnest and most peripheral.

The muscle cells of the iris are smooth muscle.

The crypts of Fuchs openings located on either side of the collarette that allow the stroma and deeper iris tissues to be bathed in aqueous humor.

Collagen trabeculae that surround the border of the crypts can be seen in blue irises.

Structure of the iris and surrounding parts showing the dilator and sphincter muscles (dilator pupillae and sphincter pupillae).

The iris controls the size of the pupil by means of contracting the iris sphincter muscle and/or the iris dilator muscle.

The size of the pupils is dependent on many factors: light, emotional state, cognitive load, arousal, stimulation, and can range from less than 2 mm in diameter, to as large as 9 mm in diameter.

There is significant variation in maximal pupil diameter by individual humans.

Pupil diameter decreases with age.

The iris contract the pupils when accommodation is initiated, to increase the depth of field.

Very few humans possess the ability to exert direct voluntary control over their iris muscles, which grants them the ability to dilate and constrict their pupils on command.

The iris is usually strongly pigmented, with the color typically ranging between brown, hazel, green, gray, and blue.

Blue-green-gray eyes are a relatively rare eye color.

Occasionally, the color of the iris is due to a lack of pigmentation, as in the pinkish-white of oculocutaneous albinism.

Rarely there is obscuration of its pigment by blood vessels, as in the red of an abnormally vascularized iris.

The only pigment that contributes substantially to normal iris color is the dark pigment melanin.

The quantity of melanin pigment in the iris is one factor in determining the phenotypic eye color.

Iris color is due to variable amounts of eumelanin-brown/black melanins, and pheomelanin-red/yellow melanins produced by melanocytes.

More of the former is found in brown-eyed people and of the latter in blue- and green-eyed people.

The limbal ring appears as a dark ring encircling the iris on some individuals, but is a result of the optical properties of the region between the cornea and sclera, not of pigments in the iris.

Iris color is a highly complex phenomenon consisting of the combined effects of texture, pigmentation, fibrous tissue, and blood vessels within the iris stroma, which together make up an individual’s epigenetic constitution in this context.

Most irises also show a condensation of the brownish stromal melanin in the thin anterior border layer, which by its position has an overt influence on the overall color.

The degree of dispersion of the melanin, which is in subcellular bundles called melanosomes, has influence on the observed color.

Melanosomes in the iris are not mobile, and the degree of pigment dispersion cannot be reversed.

Abnormal clumping of melanosomes does occur in disease and may lead to irreversible changes in iris color.

Colors other than brown or black are due to selective reflection and absorption from the other stromal components.

Sometimes, lipofuscin, a yellow wear and tear pigment, also enters into the visible eye color, especially in aged or diseased green eyes.

The optical mechanisms by which the nonpigmented stromal components influence eye color are complex, and many erroneous statements exist in the literature.

The absorption and reflection by biological molecules:hemoglobin in the blood vessels, collagen in the vessel and stroma, is the most important element.

White babies are usually born blue-eyed since no pigment is in the stroma, and their eyes appear blue due to scattering and selective absorption from the posterior epithelium.

If melanin is deposited substantially, brown or black color is seen; if not, they will remain blue or gray.

Example of heterochromia – one eye of the subject is brown, the other hazel.

Heterochromia is an ocular condition in which one iris is a different color from the other iris, or where the part of one iris is a different color from the remainder, partial heterochromia.

Uncommon in humans, it is often an indicator of ocular disease, such as chronic iritis or diffuse iris melanoma, but may also occur as a normal variant.

Sectors or patches of strikingly different colors in the same iris are less common.

In contrast, heterochromia and variegated iris patterns are common in veterinary practice.