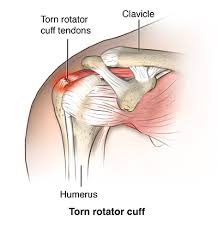

The rotator cuff refers to the tendons of the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor muscles attachment to the capsule of the glenohumeral joint.

The rotator cuff refers to the tendons of the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor muscles attachment to the capsule of the glenohumeral joint.

Rotator cuff is the major stabilizing force of the shoulder.

The mechanism of the rotator cuff centers the humeral head by compressing it into the glenoid concavity.

The muscles of the cuff provide strength in movement of internal rotation by the subscapularis muscle, elevation by the supraspinatus muscle, and external rotation by the teres and infraspinatus muscles.

Most common clinical problem of the shoulder.

Rotator cuff arthropathies refers to shoulder arthritis with a massive rotator cuff tear.

Rotator cuff tears can result from substantial traumatic injury, or can occur insidiously from atraumatic or degenerative changes.

Most patients with atraumatic or degenerative rotator cuff tear typically present with insidious onset of lateral shoulder pain, although tears may be asymptomatic.

Most rotator cuff pains may be worse at night, leading to sleep disturbances and may be exacerbated by overhead activities, such as reaching for a high shelf, or reaching behind the back in the case of a supraspinatus tear.

There may be weakness of the arm when lifting above the shoulder level.

The relevance of tear size and thickness is not clear as structural characteristics of rotator cuff tears tend to correlate poorly with the severity of symptoms.

Physical examination of the shoulder in suspected rotator cuff tear involves inspection of the shoulder girdle to assess muscle atrophy in the periscapular region, scapular posture, shoulder asymmetry, and scars from preview surgery.

The range of motion and arm strength in abduction, forward flexion, and external rotation planes are all affected by rotator cuff tears, and can be measured.

Most degenerative tears of the rotator cuff occur in adults 40 years of age or older, and its prevalence increases with advancing age.

Other risk factors for degenerative rotator cuff tear include: male sex, a history of smoking, history of manual labor, coexisting conditions leading to vascular insufficiency (hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and hypercholesterolemia) and a family history of rotator cuff tears.

Rotator cuff tears are more common in the dominant arm, and there are certain alleles associated with a higher risk.

Serious injury with pain and impaired function of the shoulder with permanent loss of the rotator cuff tendons and the normal surface of the shoulder joint.

Loss of shoulder cartilage that covers the joint surface and the tendons.

The tendons of the rotator cuff allow smooth function of the upper end of the humerus and when the tendons are degenerated or torn the upper arm rubs against the overlying bone, with weakness, pain, stiffness, and grinding on movement.

At five years of follow up, tears are enlarged in half of the people with full thickness tears and tears progressed to full thickness in approximately 1/3 of those with partial thickness tears.

The size and thickness of rotator cuff tears are not strong associated with shoulder pain and function.

Fat infiltration of rotator cuff muscles is present in 37 to 45% of patients with chronic rotator cuff tears and is associated with worse treatment outcome.

Treatment is shoulder replacement

50% of adults over the age of 55 years.

The failure of the cuff related to tear or wear processes.

Injuries divided into traumatic or degenerative tears.

May be related to a major injury, or more commonly related to age related atrophy of the tendons.

Typical deterioration starts with the undersurface of the anterior supraspinatus tendon.

Progression of the tendon failure can lead to full thickness of the supraspinatus tendon and then the infraspinatus and subscapularis tendon insertions.

Progression of cuff tendon deterioration may be slow and patients may be symptomatic and still maintain satisfactory shoulder function for at least 4 years.

More frequent in the obese.

Intrajoint corticosteroid injections not known to increase the risk of rotator cuff deterioration.

Corticosteroid injections can alter tendon and ligament collagen composition, strength and healing.

Nicotine can decrease tendon healing and its attachment to bone.

30% of asymptomatic individuals over the age of 60 have imaging studies indicating the presence of rotator cuff abnormalities.

65% of asymptomatic people over the age of 70 years have rotator cuff defects on radioimaging studies.

Clinical manifestations vary significantly from patient to patient.

With acute process from a traumatic injury full thickness cuff tears may be associated with sudden weakness in the ability to elevate the arm, while patients with chronic degeneration may have a gradual onset of shoulder weakness, with pain and crepitus.

Symptoms include weakness with lifting, impaired control of shoulder motion, pain with overhead movement and nocturnal pain.

Many patients with chronic rotator cuff degenerative changes have no symptoms.

Examination of the shoulder may reveal muscle atrophy of the deltoid, supraspinatus, infraspinatus or a mixture (Matsen).

Physical examination may reveal a defect in the cuff tendon attachment at the site of the anterior greater tuberosity of the humerus.

Crepitance may be palpated below the acromion as the arm is rotated revealing changes from the edges of the torn cuff.

On arm elevation against pressure pain or weakness may be noted and suggests involvement of the supraspinatus muscle.

Isometric testing of the arm on internal rotation with the development of pain or weakness suggests abnormality of the subscapularis muscle.

Pain or weakness during external rotation suggests involvement of the infraspinatus muscle.

With cuff defects the range of passive motion of the shoulder may be limited.

In partial thickness rotator cuff injuries limitation on internal rotation on abduction is common.

Defects associated with instability of the joint occur in the anterior, superior and posterior directions.

The humeral head can anteriorly dislocate when elevation of the arm occurs with an unstable situation known as anterosuperior escape.

Anterosuperior escape occurs as a result of wear or surgical impairment of the coracoacromial arch.

Pseudoparalysis of the arm occurs when the humeral head is destabilized in the glenoid concavity causing contraction of the deltoid muscle which then is ineffective in elevating the arm away from the side.

Plain radiographs of the shoulder may demonstrate upward displacement of the humeral head relative to the glenoid.

Radiographs may show narrowing of distance or even contact of the acromion and humeral head in patients with chronic cuff deterioration.

Radiographs are not used to diagnose rotator cuff tears, but they can provide information on other potential sources of shoulder pain, such as osteoarthritis and dislocation.

Large chronic rotator cuff tears, x-ray findings include proximal humeral, head, migration, loss of Areo, humeral, interval, and superior glenoid.

Ultrasound and MRI both 90% accurate in diagnosis of full thickness and partial thickness tears, with sensitivities as high as 97% and specificities of 67% when compared to findings at arthroscopy (Teefey).

Ultrasound and MRI can confirm rotator cuff tears and provide information on size and location, tendon retraction, and muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration.

Ultrasonography of the shoulder is relatively inexpensive and portable and has a sensitivity and specificity similar to those of MRI for a diagnosis of full thickness rotator cuff tear.

MRI has better image quality and better definition of muscle tissue.

Lack of quality controlled and randomized studies make the approach to treatment based on clinicians experience using management principles of other tendon site failure areas, such as the hand and knee.

Acute complete tears should be repaired as soon as possible and usually by 6 weeks following the injury.

Acute rupture injuries, if not repaired, will result in retraction and resorption of the detached tendon with associated muscle atrophy.

Partial thickness tears that are acute or chronic may improve with nonsurgical treatment aimed to prevent the intact tendon from retracting and causing muscle atrophy: physical therapy to provide range of motion exercises to enhance adduction, internal rotation up the back and with the arm in abduction.

For tears related to degeneration physical therapy is usually recommended to determine non-operative response.

Physical therapy works by addressing periscapula muscle weakness, correcting scapular posture, and improving rotator cuff muscle strength and endurance, correct deficits in the range of motion of the glenohumeral joint, and allows the shoulder to move through the full arc of motion, decreasing the work of the rotator cuff musculature.

Studies revealed more than 80% of patients receiving supervised physical therapy report reduce pain and improve function at six months to one year of follow up with physical therapy.

Most full thickness tears and those that are complete will require surgery.

Injection of corticosteroids can decrease inflammation in the bursa, the main source of pain.

Corticosteroids do not lead to healing of the rotator cuff tendon.

Repeated corticosteroids can lead to cartilage and rotator cuff degeneration.

Anti-inflammatory medications can decrease inflammation in the bursa.

Expert consensus is that traumatic rotator cuff tears should be treated up soon after diagnosis to avoid long-term consequences such as rotator cuff muscle degradation and tendon retraction.

Most patients with symptomatic degenerative rotator cuff disorders can be treated non-operatively.

Patients not treated with surgery may progress with time and follow-up is required in patients with full thickness tears treated conservatively.

Most cases can be treated with physical therapy as an appropriate initial step.

Majority of surgical repairs consist of mini-open repairs and arthroscopic repairs.

Surgery, which is most commonly performed arthroscopically involves repairing the torn tendon and resecuring it to the humerus to allow for tendon to bone healing.

Rotator cuff surgery has a very low incidence of complications.

Postoperative stiffness occurs in approximately 10% of patients and deep vein thrombosis, and infection occur in less than one percent of cases.

Open repairs reserved for difficult and retracted tears with the need of tendon transfers and tissue augmentation.

Goal of surgery is to mobilize the torn tendon, free-up scar tissue, decompress the bursa by removing the acromial spur, and fixation of the torn rotator cuff tendon .

Open repair requires a 5-6 cm incision over the edge of the shoulder.

With open rotator cuff repairs the anterior deltoid is detached from the clavicle and acromion, and an open acromioplasty is performed allowing identification of the full thickness rotator cuff tear and mobilization of the torn tendon.

Torn tendons are repaired to its insertion with sutures through bone tunnels or suture anchors at the insertion site, and then the anterior deltoid is repaired back to its origin at the acromion.

Open procedures are associated with greater amounts of postoperative pain than with closed procedures.

A mini-open technique combines both arthroscopic and open approach.

A mini-open rotator cuff repair starts with arthroscopy with subacromial decompression, identification of the torn tendon and then a small incision is made to split the deltoid muscle and the torn tendons visualized, mobilized and fixed to their attachments using sutures via bone tunnels or suture anchors.

Torn mini-open cuff repairs have a success rate equal to open repairs with fewer complications and pain.

Evidence is lacking for psychosocial support, the use of manual therapy, massage therapy, acupuncture, therapeutic ultrasound, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, shockwave therapy, or post electronic electromagnetic field therapy.

Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, may provide pain relief and chronic muscular pain in tendinitis, but lack high degree of evidence supporting their specific use in rotator cuff disorders.

Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, reduce pain modestly in patients with rotator cuff disorders.

Opioid drugs are generally not recommended for rotator cuff disorders due to risks.

Acetaminophen has little and no benefit in patients with rotator cuff disease regarding pain and function, compared with placebo.

Evidence is lacking for the use of pain modulating drugs, such as gabapentin, duloxetine, and pregabalin.

Injection of a glucocorticoid together with a local anesthetic provides symptomatic pain relief in patients with rotator cuff disorders as compared with placebo: evidence is inconsistent and limited to small trials showing short term benefit for up to four weeks.

The use of orthobiologic or regenerative medicine therapies are not currently recommended for the treatment of rotator cuff disorders: data from randomized control trials supporting the effectiveness of these treatments are lacking.